This Post took a couple of days to do, between work, sleep and work..you know how it goes. I remembered reading about this on wiki a year or so ago. I decided to do a post on something that didn't relate to politics but to history, something that I am a fan of. When I was looking at the pics of the Graf, I could see the similarities with the Japanese designs but with a German twist. I found out that the Germans had gone to Japan to examine the Japanese carrier Akagi, and the designs bear this out. I dug out references from several location from google and "Wiki" to show pics and information on the German carrier. The fate of the Graf showed me that the Germans suffered from "Tactical" mindset and not strategic planning. Their equipment designs and combat tactics reflected this mindset. If the Germans had gotten their capital ships going, the battle of the Atlantic might have had a different outcome.

A combination of political infighting between the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe, disputes within the ranks of the Kriegsmarine itself and Adolf Hitler's waning interest all conspired against the carriers. A shortage of workers and materials slowed construction still further and, in 1939, Raeder reduced the number of ships from four to two. Even so, the Luftwaffe trained its first unit of pilots for carrier service and readied it for flight operations. With the advent of World War II, priorities shifted to U-boat construction; one carrier, Flugzeugträger B, was broken up on the slipway while work on the other, Flugzeugträger A (christened Graf Zeppelin) was continued tentatively but suspended in 1940. The air unit scheduled for her was disbanded at that time.

The role of aircraft in the Battle of Taranto, the pursuit of the German battleship Bismarck, the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Battle of Midway demonstrated conclusively the usefulness of aircraft carriers in modern naval warfare. With Hitler's authorization, work resumed on the remaining carrier. Progress was again delayed, this time by the demand for newer planes specifically designed for carrier use and the need for modernizing the ship in light of wartime developments. Hitler's disenchantment with the performance of the Kriegsmarine's surface units led to a final stoppage of work. The ship was captured by the Soviet Union at the end of the war and sunk as a target ship in 1947.

Graf Zeppelin is launched, 8 December 1938.

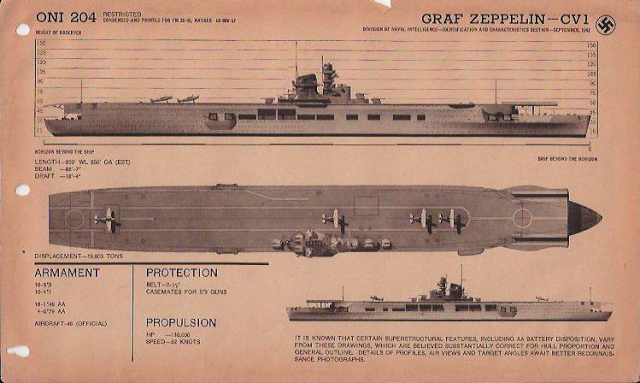

The design staff decided that the new carrier would need to be able to defend itself against surface combatants, which necessitated armor protection to the standard of a heavy cruiser. A battery of sixteen 15 cm (5.9 in) guns were deemed sufficient to defend the ship from destroyers. In 1935, Adolf Hitler announced that Germany would construct aircraft carriers to strengthen the Kriegsmarine. A Luftwaffe officer, a naval officer, and a constructor visited Japan in the autumn of 1935 to obtain flight deck equipment blueprints and inspect the Japanese aircraft carrier Akagi. The Germans also unsuccessfully attempted to examine the British carrier HMS Furious.

The keel of Graf Zeppelin was laid down on 28 December 1936, on the slipway that had recently held the battleship Gneisenau. The ship was built by the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel. Two years later, Großadmiral (Grand Admiral) Erich Raeder presented an ambitious shipbuilding program called Plan Z which would build up the Kriegsmarine to a point where it could challenge the British Royal Navy in the North Sea. Under Plan Z, by 1945 as part of the balanced force the navy would have four carriers; the pair of Graf Zeppelin-class ships were the first two in the plan. Hitler approved the construction program on 1 March 1939. In 1938, a second carrier, ordered under the provisional name "B", was laid down at the Germaniawerft dockyard in Kiel. Graf Zeppelin was launched on 8 December 1938.

The Graf Zeppelin class's hull was divided into 19 watertight compartments, the standard division for all capital ships in the Kriegsmarine. Their belt armor was to vary from 100 mm (3.9 in) over the machinery spaces and aft magazines, to 60 mm (2.4 in) over the forward magazines and tapered down to 30 mm (1.2 in) at the bows. Stern armor was kept at 80 mm (3.1 in) to protect the steering gear. Inboard of the main armor belt was a 20 mm (0.79 in) anti-torpedo bulkhead.

Graf Zeppelin at Kiel, June 1940, displaying her newly

rebuilt bow. Also visible are her 15 cm casemate guns, before their

removal to defend occupied Norway. The photo is marked Geheim ("secret").

The Graf Zeppelins' original length-to-beam ratio was 9.26:1, resulting in a slender silhouette. However, in May 1942, the accumulating top-weight of recent design changes required the addition of deep bulges to either side of Graf Zeppelin's hull, decreasing that ratio to 8.33:1 and giving her the widest beam of any carrier designed prior to 1942. The bulges served mainly to improve Graf Zeppelin's stability but they also gave her an added degree of anti-torpedo protection and increased her operating range because selected compartments were designed to store approximately 1500 tons more fuel oil.

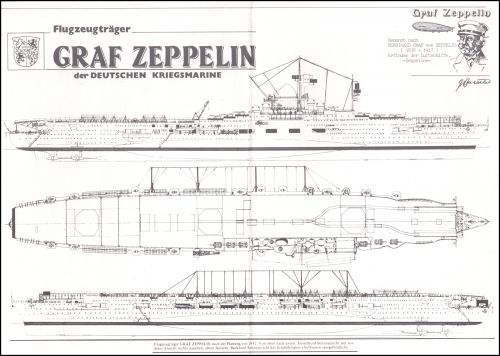

Graf Zeppelin's straight-stemmed prow was rebuilt in early 1940 with the addition of a more sharply angled "Atlantic prow", intended to improve overall seakeeping. This added 5.2 m (17 ft) to her overall length.The Graf Zeppelins' steel flight deck, overlaid with wooden planking, was 242 m (794 ft) long by 30 m (98 ft) wide at its maximum. It had a slight round down right aft and overhung the main superstructure but not the stern; being supported by steel girders. At the bow, the carriers were to have an open forecastle and the leading edge of her flight deck was uneven (mainly due to the blunt ends of her catapult tracks), but it did not appear likely that would have caused any undue air turbulence. Careful wind-tunnel studies using models confirmed this, but they also revealed that their long low island structure would generate a vortex over the flight deck in these tests when the ship yawed to port. This was considered to be an acceptable hazard when conducting air operations.[16]

Hangars

The Graf Zeppelin class's upper and lower hangars were long and narrow with unarmored sides and ends. Workshops, stores and crew quarters were located outboard of the hangars, a design feature similar to that of British carriers. The upper hangar measured 185 m (607 ft) x 16 m (52 ft); the lower hangar 172 m (564 ft) x 16 m (52 ft). The upper hangar had 6 m (20 ft) vertical clearance while the lower hangar had 0.3 m (1 ft 0 in) less headroom due to the ceiling braces. Total usable hangar space was 5,450 m2 (58,700 sq ft) with stowage for 41 aircraft: 18 Fieseler Fi 167 torpedo bombers in the lower hangar; 13 Junkers Ju 87C dive bombers and 10 Messerschmitt Bf 109T fighters in the upper hangar.Aircraft

In late 1938, the Technische Amt RLM (Technical Office of the Reichsluftfahrtministerium or State Ministry of Aviation) requested that Messerschmitt's Augsburg design bureau draw up plans for a carrier-borne version of the Bf 109E fighter, to be designated Bf 109T (the "T" standing for Träger or Carrier). By December 1940, the RLM decided to complete only seven carrier-equipped Bf 109T-1s and to finish the remainder as land-based T-2s since work on Graf Zeppelin had ceased back in April and there appeared to be little likelihood she would then be commissioned any time soon. When work on Graf Zeppelin ceased, the T-2s were deployed to Norway. At the end of 1941, when interest in completing Graf Zeppelin revived, the surviving Bf 109 T-2s were withdrawn from front-line service in order to again prepare them for possible carrier duty. Seven T-2s were rebuilt to T-1 standards and handed over to the Kriegsmarine on 19 May 1942. By December, a total of 48 Bf 109T-2s had been converted back into T-1s. 46 of these were stationed at Pillau in East Prussia and reserved for use aboard the carrier. By February 1943, however, all work on Graf Zeppelin had ceased and the aircraft were returned to Luftwaffe service in April.

Work on developing a torpedo-carrying version of the Ju 87D for anti-shipping sorties in the Mediterranean had already commenced in early 1942 when the possibility again arose that Graf Zeppelin might be completed. As the Fieseler Fi 167 was now considered obsolete, the Technische Amt requested that Junkers modify the Ju 87D-4 into a carrier-borne torpedo-bomber/recon plane to be designated Ju 87E-1. But when all further work on Graf Zeppelin was halted for good in February 1943, the entire order was canceled. None of the Ju 87Ds converted to carry a torpedo were used operationally. By May 1942, when work was ordered resumed on Graf Zeppelin, the older Bf 109T carrier-borne fighter was considered obsolete. By September 1942 detailed plans for the new fighter, the Me 155, were completed. When it became apparent Graf Zeppelin would not be commissioned for at least another two years, Messerschmitt was unofficially told to shelve the projected fighter design. No prototype of the carrier-borne version of the plane was ever constructed.

On 1 August 1938, four months prior to Graf Zeppelin's launch date, the Luftwaffe formed its first carrier-based air unit, designated Trägergruppe I/186, on Rugia Island near Burg. It was composed of three squadrons (Staffeln) and was intended to serve aboard both carriers when completed. By October, however, shipyard construction delays resulted in disbandment of the air group as it was considered too large and costly to maintain given the uncertainty over when the two vessels would be ready for sea trials. Instead, on 1 November that same year a single fighter squadron (Trägerjagdstaffel) was created, 6./186, and placed under the command of Cpt. Heinrich Seeliger. Later, a dive bomber squadron was added, 4./186, equipped with Ju 87Bs under Cpt. Blattner. Six months after, in July 1939, a second fighter squadron was formed, 5./186, under Oberleutnant Gerhard Kadow and partly staffed with pilots culled from 6./186. By August the three squadrons were reorganised into Trägergruppe II/186 under the command of Major Walter Hagen in anticipation that Graf Zeppelin would be ready for service trials by the summer of 1940.

Fate after the war

In April 1943 Graf Zeppelin was towed eastward, first to Gotenhafen, then to the roadstead at Swinemünde and finally berthed at a wharf in the Parnitz River, two miles from Stettin.There she languished for the next two years with only a 40-man custodial crew in attendance. When Red Army forces neared the city in April 1945, the ship’s Kingston valves were opened, flooding her lower spaces and settling her firmly into the mud in shallow water.

At 6pm on April 25th 1945, just as the Russians entered Stettin, commander Wolfgang Kähler radioed the squad to detonate the explosives. Smoke billowing from the carrier’s funnel confirmed the charges had gone off, rendering the ship useless to her new owners for many months to come.

The Soviets decided to repair the damaged ship and it was refloated in March 1946 and enlisted in the Baltic Fleet as aircraft carrier Zeppelin. The last known photo of the carrier is dated April 7th, 1947.

For many years, no other information about the ship’s fate was available. After the opening of the Soviet archives, new light was shed on the mystery. What is known is that the carrier was as “PB-101” (Floating Base Number 101) in February 3, 1947, until, on August 16, 1947, it was used as a practice target for Soviet ships and aircraft.

Allegedly the Soviets installed aerial bombs on the flight deck, in hangars and even inside the funnels (to simulate a load of combat munitions), and then dropped bombs from aircraft and fired shells and torpedoes at it.

By this point, the Cold War was underway, and the Soviets were well aware of the large numbers and central importance of aircraft carriers in the U.S. Navy, which in the event of an actual war between the Soviet Union and the United States would be targets of high strategic importance.

After being hit by 24 bombs and projectiles, the ship did not sink and had to be finished off by two torpedoes. The exact position of the wreck was unknown for decades.

The Wreck was discovered in 2006 by Polish researchers in the Baltic off Władysławowo, at the head of the Hel Peninsula.

Thanks for the history lesson! Learned a few things I didn't know! :-)

ReplyDeleteThis is a chunk of history I knew nothing about. Doubtful one or two carriers would have made a difference for Germany, but their failure to complete what they started perhaps shows a conventional continental mindset leading up to what became world war.

ReplyDelete