In 1980 Ronald Reagan was elected and he expressed open pride in the United States and he immediately pushed through several large budget increases to bring the services back up to bar after years of neglect after the Vietnam war. We had gone to a volunteer service, not drafted and the pay was increased after several public embarrassments of servicemen having to be on food stamps to support their families because the pay and benefits were so bad. By the mid 1980's the service were flush with funds for training, equipment and confidence. Grenada was a positive boost to our morale despite all the problems that were uncovered. I joined in 1985 and went to basic in Fort Lost in the Woods in Misery.(Fort Leonard Woods in Missouri). I remembered hearing about the "fragging" and other disciplinary issues the Army was having at the tail end of Vietnam and the aftermath. My dad was an MP his first tour in Vietnam and was "El CID" the tour in 1972 He did talk about that kind of stuff with his fellow Soldiers, I was a little kid but I did hang around and listen. While I was in basic, they covered in great detail what would happen if we disobeyed the UCMJ and we would be in Leavenworth making gravel for the Colonels driveway. I remembered wondering when I went in would I see the same kind of stuff in the service that I remembered reading about and remembering what my dad talked about. It was a totally different environment than I expected, total professionalism, we trained hard and had excellent morale. This was reinforced when I got sent to Germany to the Stuttgart area. We expected the Soviets to run through the Fulda gap like cockroaches in New York Apartment.

I spent a lot of time inside the 1KM zone during my first tour and the Officers and NCO's were top notch, we trained really hard and we were implementing the new "Airland" battle that the Army was rolling out to disrupt the Soviet echelons if they attacked.

We trained hard for an attack that never came, the Soviet Union collapsed due to economic problems. We tested our tactics and procedures on the Iraqi's as we evicted them out of Kuwait and punished them. Iraq had the distinction of having rotten timing, if they had waited a couple of years then grabbed Kuwait, we may not have been able to do "Desert Storm". After the Soviet Union basically collapsed, the Military was under a lot of pressure to cut back the force for the "Peace dividend" that the politicians were expected to spend on social projects. I and many of my fellow soldiers got sent to the Gulf and we completed the mission. After I got out, I went from job to job, my Military Occupational Specialty had no civilian counterpart. In finally settled down and got married and got hired by Ford Motor Company, and I was in a store looking at books and ran across this one and bought it.

You can buy your own copy off Amazon, it is very good.

I bought this book and read it, and it totally engrossed me, it explained how the Officers that won in the desert what their experiences were, how their peers transformed a shattered military with non existent morale and worn out equipment changed the culture, mindset and ultimately changed how we fight. The book talked about how America changed and this reflected in the quality of men and women that were enlisting and decided to serve.

This were a couple of the reviews of the book.

Freelance journalist Kitfield relies heavily on personal accounts

in this story of the officers who reshaped the U.S. Army and Air Force

after the experience of Vietnam and then led our troops in Operation

Desert Storm. In the 1970s the U.S. began to adjust to a professional

military after depending on the Selective Service system. In the 1980s,

increased defense budgets enabled the modernization of arsenals and the

stockpiling of supplies and equipment, while cumbersome higher command

systems were simplified. By the time of Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in

1990, America's military leaders were eager to demonstrate what 20 years

of reform had wrought. This is a highly favorable account of that

effort.

Copyright 1994 Reed Business Information, Inc.

From Library Journal

The transformation of the American armed forces from the

dispirited shell-shocked military at the close of the Vietnam era to the

superbly trained, highly motivated, and universally respected victors

in the Persian Gulf War is as dramatic a tale as any in American

military history. Kitfield, an award-winning journalist on defense

issues, follows the careers of dozens of army, navy, air force, and

marine officers from their early service years in Vietnam to their

success as commanders in the defeat of the Iraqis. While organizational

and technical issues play a role, the book concentrates on the human

aspect of this startling redirection of the U.S. military. A useful

supplement to Michael Gordon's The Generals' War (LJ 12/94) and Al

Santoli's overlooked Leading the Way (LJ 9/15/93), this is an essential

addition to Vietnam and Persian Gulf War collections. Strongly

recommended for academic and public libraries.As we draw down after the Wars in Iraq and still fighting the war in Afghanistan, we have had no incidence of "fragging" that I am aware of. I do know that a muslim soldier shot up a tent full of officers right before the invasion of Iraq in 2003, other than that I am not aware of any. I get into arguments that state that we need to "bring back the Draft". I say "NO", You get a far better quality of recruit when people volunteer vs getting drafted. This helps a lot with mindset and discipline, you get far less resentment and hostility from someone that enlisted vs getting told to "Report or else".

I ran across this article and I really liked it so I snagged it.

During its long withdrawal from South Vietnam, the U.S. military experienced a serious crisis in morale. Chronic indiscipline, illegal drug use, and racial militancy all contributed to trouble within the ranks. But most chilling of all was the advent of a new phenomenon: large numbers of young enlisted men turning their weapons on their superiors.

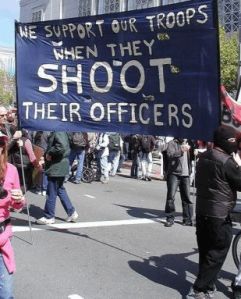

The Vietnam War was one of the least popular in American history. It was also the least “popular” with the GI’s who were sent to fight it. By the late 1960’s, news of GI unrest was being carried on TV and in newspapers around the country and Vietnam vets were speaking at anti-war demonstrations.

But word of the GI resistance in Vietnam itself trickled back more slowly – the soldiers flashing peace signs and Black Power salutes, the group refusals to fight, anti-war petitions and demonstrations, and even the fragging of officers. What we’ve read in the newspapers, however, has just been bits and pieces. Seldom have we had a chance to hear the whole story from the GI’s themselves.

These battle weary troops from the 1st Air Cav. had just staged a “combat refusal” at Firebase Pace.

The dictionary defines “fragging” as the term used to describe the

deliberate killing or attempted killing by a soldier of a fellow

soldier, usually a superior officer or non-commissioned officer (NCO).

Fragging often consisted of throwing a grenade into a tent where the

target was sleeping or in the shitters. The word was coined by U.S.

military personnel during the Vietnam War when such killings were most

often attempted with a fragmentation grenade, sometimes making it appear as though the killing was accidental or during combat with the enemy.The high number of fragging incidents in the latter years of the Vietnam War was symptomatic of the unpopularity of the war with the American public and the breakdown of discipline in the U.S. Armed Forces. Documented and suspected fragging incidents totaled nearly eight hundred from 1969 to 1972; resulting in 86 deaths and 714 injuries. In 1971, army testimony before Congress cited the following: 126 incidents in 1969, 271 in 1970, and 333 in 1971. I couldn’t find a count for 1972, but it’s unlikely fragging suddenly ceased.

So why purposely try to kill a soldier with a higher rank?

Most fragging was perpetrated by enlisted men against leaders. Enlisted men, in the words of one company commander, “feared they would get stuck with a lieutenant or platoon sergeant who would want to carry out all kinds of crazy ‘John Wayne’ tactics, who would use their lives in an effort to win the war single-handedly, win the big medal, and get his picture in the hometown paper.” Harassment of subordinates by a superior was another frequent motive. The stereotypical fragging incident was of “an aggressive career officer being assaulted by disillusioned subordinates.” Several fragging incidents resulted from alleged racism between African American and white soldiers. Attempts by officers to control drug use caused others. Most known fragging incidents were carried out by soldiers in support units rather than soldiers in combat units.

Soldiers sometimes used non-lethal smoke and tear-gas grenades to warn superiors that they were in danger of being fragged if they did not change their behavior. A few instances occurred—and many more were rumored—in which enlisted men collected “bounties” on particular officers or non-commissioned officers to reward soldiers for fragging them.

In short, for all the tales of soldiers assaulting gung-ho officers they feared would get them killed, a more likely explanation is that fragging was the work of rear-echelon misfits with anger management and substance issues who sulked after getting chewed out and decided to have their revenge. The nature of the war as such likely contributed only indirectly — its unpopularity discouraged enlistment and compelled the military to accept more trouble-prone recruits. The prevalence of drugs couldn’t have helped either — one study of soldiers returning from Vietnam found one-fifth had been addicted to narcotics.

Contrary to Hollywood’s take on Vietnam, most of the drug and discipline problems were in rear echelon bases – not in the bush. The combat units largely remained cohesive. Boredom, poor morale and lack of discipline were a combustible mix. For fear of being fragged some leaders turned a blind eye to drug use and other indiscipline among the men in their charge.

After the Tet Offensive in January and February 1968, the Vietnam War became increasingly unpopular in the United States and among American soldiers in Vietnam, many of them conscripts. Secondly, racial tensions between white and African-American soldiers and marines increased after the assassination of Martin Luther King in April 1968. With soldiers reluctant to risk their lives in what was perceived as a lost war, fragging was seen by some enlisted men “as the most effective way to discourage their superiors from showing enthusiasm for combat.”

- On the evening of October 22, 1970, Company L of the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment was engaged in anti-infiltration operations in the “Rocket Belt,” an area of more than 500 square kilometers ringing the Da Nang Airbase. The company was set up in bunkers at an outpost on Hill 190, to the west of Da Nang. Assigned to guard duty that night, Private Gary A. Hendricks settled into his position on the perimeter and made himself comfortable. Too comfortable, it turned out. A bit later, when Sergeant Richard L. Tate, the sergeant of the guard, discovered Hendricks sleeping on post, he gave the private a tongue lashing but took no further action. Shortly after midnight the next day, Hendricks tossed a fragmentation grenade into the air vent of Sergeant Tate’s bunker. The grenade landed on Tate’s stomach and the subsequent blast blew his legs off, killing the father of three from Asheville, North Carolina, who had only three weeks left on his tour of duty. The explosion injured two other sergeants who were also in the bunker.

- Journalist Eugene Linden, in a 1972 Saturday Review article, described the practice of “bounty hunting” whereby enlisted men pooled their money to be paid out to a soldier who killed an officer or sergeant they considered dangerous. One well-known example of bounty hunting came out of the infamous Battle of Dong Ap Bai, aka Hamburger Hill, in May 1969. After suffering more than 400 casualties over 10 merciless days of attacks to take the hill, the 101st Airborne Division soldiers were ordered to withdraw about a week later. Shortly thereafter, the army underground newspaper in Vietnam, GI Says, reportedly offered a $10,000 bounty on the very aggressive officer who led the attacks, Lt. Col. Weldon Honeycutt. Several unsuccessful attempts were reported to have been made on the colonel’s life.

- In April 1971, Democratic leader Mike Mansfield of Montana emotionally spoke to the issue on the floor of the Senate. Mansfield related details of the death of 1st Lt. Thomas A. Dellwo, of Choteau, Mont. “He was not a victim of combat. He was not a casualty of a helicopter crash or a jeep accident. In the early morning hours of March 15, the first lieutenant from Montana was ‘fragged’ as he lay sleeping in his billet at Bien Hoa. Lt. Richard Harlan was also killed in the incident. He was murdered by a fellow serviceman, an American GI. Private E-2 Billy Dean Smith was charged with killing the officers but was acquitted in November 1972.

- On 21 April 1969, a grenade was thrown into the company office of K Company, 9th Marines, at Quảng Trị Combat Base, RVN; First Lieutenant Robert T. Rohweller died of wounds he received in the explosion. Private Reginald F. Smith pleaded guilty to the premeditated murder of Rohweller and was sentenced to 40 years’ imprisonment; he died in custody on 25 June 1982.

If you shoot someone, there’s a lot of more forensic evidence. And the Army is pretty fanatical about keeping track of ammunition. A bullet can be traced to a particular lot number or a particular gun. You can’t associate a grenade firing pin with a particular grenade.

With a grenade, it splinters

into thousands of tiny fragments. Trying to piece that together, there’s

no way you’re going to get evidence off of that. Avoiding getting

fingerprints on the spoon [the lever on a grenade that is held down to

prevent it from going off] is pretty easy — just don’t touch the spoon

with the tip of your finger.

Also, with a gun, you have to

be there to shoot it. Whereas with a grenade, you have a certain amount

of lead time. You could set it up as a booby trap if you wanted to, with

a trip wire, or set it against a piece of furniture. There are many

more ways you can make a grenade deadly that you can’t make a gun.

In Vietnam, it was really not

that hard to get your hands on grenades. There were lax standards, which

meant that there were crates of grenades available. You’d make your

stop by the ammunition bunker, and platoon members could grab a couple

or as many as they thought they needed.

- Here’s an example of a shooting in a base camp: Sp4 Enoch ‘Doc’

Hampton, an African American soldier, was respected and well-liked by

his fellow soldiers, he was top notch and knew how to take care of them

in the field. The First Sergeant, Clarence Lowder, whom they called “Top

did everything by the book. When on stand down at the basecamp, Top

continuously harassed Doc for the length of his ‘picked out’ hair,

threatening Article 15’s if he didn’t immediately get his hair cut. That

night at chow, Doc Hampton said he was going to the orderly room to see

the First Sgt. “Either I’ll come out alone,” he said, “or neither of us

is coming out.”

Hanusey, the clerk, was working in the orderly room when Doc came through the doorway. “His face was cold, stone cold,” Hanusey said. “He looked like a man in the movies who was about to kill.” The barrel of Doc’s M-16 was pointed downward, his feet planted firmly apart. Slowly he raised the barrel and fired a full clip into Top. The sergeant’s back exploded as pieces of flesh and blood spattered all over the orderly room. Then Doc walked out and headed to the company latrine where he barricaded himself for a possible shoot-out with arriving MP’s. Surprisingly, his fellow soldiers also armed themselves and quickly formed a perimeter around the latrine to protect their brother in arms and preventing the MP’s from reaching Doc. The siege was short-lived when a single shot sounded from the latrine…Enoch ‘Doc’ Hampton took his own life.

Only a few ‘fraggers’ were identified and prosecuted. It was often difficult to distinguish between fragging and enemy action. A grenade thrown into a foxhole or tent could be a fragging, or the action of an enemy infiltrator or saboteur. Enlisted men were often close-mouthed in fragging investigations, refusing to inform on their colleagues out of fear or solidarity. Only about 10 percent of all fragging incidents actually ended up being adjudicated. Although the sentences prescribed for fragging were severe, the few men convicted often served fairly brief prison sentences.

For every actual fragging incident, there was an untold number of threats of fragging. These threats were made in various forms, such as the surreptitious placement of a grenade or grenade pin, or perhaps the detonation of a nonlethal gas or smoke grenade, in the potential victim’s quarters or work areas. Officers who survived fragging attempts often did not discover the identity of their attackers, and as a consequence they lived in constant fear the attacks would be repeated. According to Captain Barry Steinberg, an Army judge who presided over a number of fragging courts-martial, once an officer had been threatened with fragging, he was intimidated to the point of being “useless to the military because he can no longer carry out orders essential to the functioning of the Army.”

Twenty-eight soldiers were arrested in Vietnam and tried for fragging a superior officer. Ten were convicted of murder and served sentences ranging from ten months to thirty years with a mean prison time of about nine years.

In summary, eighty percent of the murders happened at base camps, not in the field; (b) 90 percent of the assaults took place within three days after an argument with the victim; (c) offenders typically felt they had been unfairly treated; (d) 88 percent of attackers were drunk or high when they did it; (e) on average they had been in Vietnam for six months; (f) 26 of the 28 were volunteers, not draftees; (g) only five had graduated from high school; and (h) many were loners or had psychological problems.

But since the start of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the military has charged only one Soldier with killing his commanding officer, a dramatic turnabout that most experts attribute to the all-volunteer military.

I've got another category of Vietnam fragging for you: gays.

ReplyDelete20+ years ago, a co-worker stated that he had raised the lid/cover/hatch of a dugout/bunker, and upon seeing two guys screwing, had pulled the pin on a frag and tossed it at them. The impression I got was that they died.

No idea if it was a totally true story, enhanced somewhat, or complete bullshit. I gathered that he thought they were a base or group security issue that he was eliminating. Details are fuzzy at this point.

Hey Will;

DeleteIt is possible that the deaths were ruled "death by combat due to sapper attacks", there was a lot of that, the VC would try to sneak through the perimeter for assorted mischief or it was bombastic rhetoric. At this stage, there is no way to ever know. Thanks for passing that one in.

There were incidents in the field, but those were usually chalked up to enemy action... Especially against gung ho 2nd LTs...

ReplyDeleteAt the end of the Vietnam war, anyone being "gungho" had a risk of that, the morale was so bad, people saw the writing on the wall and knew that end was near.

Delete