Vasili Arkhipov was a Soviet naval officer who, upon making a split second decision, prevented the Cuban Missile Crisis from escalating into a nuclear war.

It is fitting to begin three years after Mr. Arkhipov’s death. On October 13, 2002, on the 40th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the director of the National Security Archive Thomas Blanton remarked that “a guy called Vasili Arkhipov saved the world.”

After that, he spent two years in the Caspian Higher Naval School and went on to do submarine service on vessels from the Soviet Navy’s Black Sea, Baltic, and Northern Sea fleets. In 1961, he became deputy commander of the new Hotel-class missile submarine K-19.

At a time when the U.S. and the Soviets were locked in a costly arms race, the K-19 was a new vessel the Soviets hoped would provide them with the ability to launch their missiles at their Cold War rival.

During exercises in the North Atlantic, the K-19 suffered a major leak in its reactor coolant system. The long-range radio had also been disabled during another incident, rendering the sub unable to contact its HQ in Moscow. This incident saw several crew members, along with Arkhipov, exposed to radiation.

Arkhipov backed Captain Nikolai Vladimirovich Zateyev, who feared that the crew would mutiny out of sheer desperation, by helping him dump most of the ship’s small arms arsenal overboard in order to avert the possibility that this potential mutiny would be an armed one.

The K-19 finally made it to another Soviet submarine and its crew was evacuated. The K-19 was then towed home. This incident, it can be safely assumed, had a profound effect on Arkhipov.

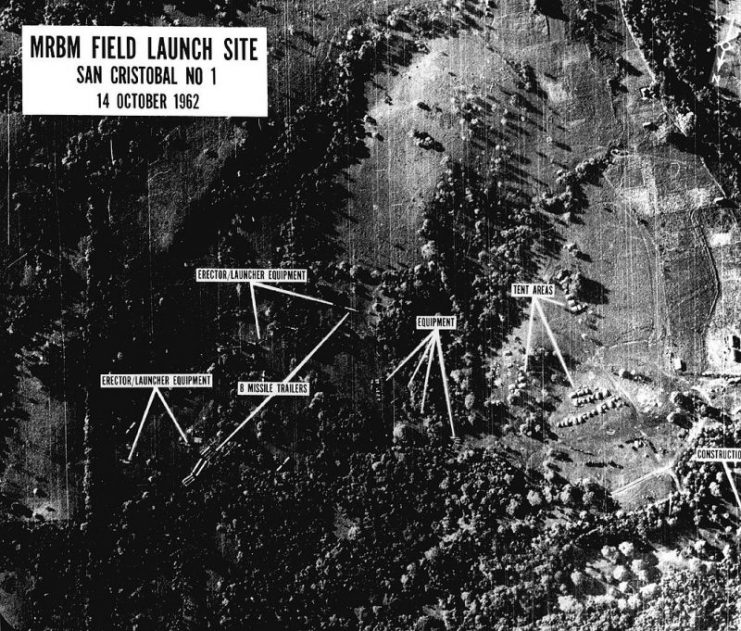

About a year later during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Arkhipov was second-in-command of the Soviet Foxtrot-class submarine B-59 which was operating near Cuba at the time. As the crisis escalated, U.S. naval vessels, clearly unaware of the fact that Soviet submarines operating in the area were carrying nuclear torpedoes, dropped depth charges on those vessels in a bid to get them to surface so that they would not break the United States naval blockade on Cuba.

The three officers who were authorized to launch this torpedo, which included Arkhipov, the captain, and the vessel’s political officer, Ivan Semonovich Maslennikov, quickly reviewed their options. The captain and the political officer were in favor of firing. Arkhipov argued against launching the torpedo stating they should await orders from Moscow.

They were forced to surface at the behest of the fleet of eleven U.S. Navy destroyers and the aircraft carrier that was engaging them. It was then they learned that no shooting war had broken out between the US and Soviet forces, but by arguing against the launching of the nuclear-tipped torpedo, Arkhipov in effect had averted the start of a nuclear war between the two superpowers.

It is worth noting that when coming under fire Arkhipov knew he was risking two things; getting killed by simply surfacing if a shooting war was in fact underway and starting a nuclear war by returning fire in such a manner if one wasn’t underway. So his coolness in making a potentially fatal decision under such serious circumstances spoke well of him.

As for Arkhipov, after those two dangerous episodes in the early 1960s, he continued to serve in the Soviet Navy, eventually being promoted to rear admiral and becoming head of the Kirov Naval Academy. He retired in the mid-1980s and died in 1999.

He died an unsung hero and even to this day the fateful decision he took on October 27, 1962, is relatively unacknowledged and not widely known.

His name is well known in 'certain' circles... :-)

ReplyDeleteHey Old NFO;

DeleteI kinda figured that ;)