I know that other services handled defeat like the Germans did from WWI, it still gave them national pride, but the German defeat from WWII was total. The national identity was totally decimated from the war and the Germans were a people with out morals or anything, it was like they had to atone for the sins of their past and nothing was off limits. When Germany became its own nation in 1949 they started to form their own identity and move beyond the horrors and deprivation of the war.

I am not sure what we would do if we lost an entire field Army, if half of the population would rejoice in the loss because they hate what the United States is and want to see us lessened. It is interesting although distasteful exercise.

Training for Defeat

In the U.S. Army we have a long tradition of victory – or so we tell ourselves. We proudly carry the campaign streamers from past conflicts on our unit colors and enjoy hearing about the exploits of past heroes. Victory is our expectation. But what if that isn’t what happens? Now, I’m not talking about the nebulous idea of strategic victory in places like Vietnam, Iraq, or Afghanistan; I’m talking about the sharp and nasty feeling of operational and tactical defeat. Retreat. Withdrawal. Being overrun. Loss of soldiers. Loss of entire units. Disaster.

And yes, we do train for some loss: vehicle recovery, casualty evacuation, and breaking contact come to mind. But how well do those test a unit for a full and total breakdown? Or is it perhaps better to not even put that idea into soldiers’ heads? These are the questions we should at least be asking, as leaders.

Fortunately – or rather unfortunately – we have no end of historical examples of loss and defeat in the U.S. Army to use as case studies – even if we are loathe to study them or admit that they exist.

The first thing to remember is that there are varying levels of loss. The first is the most desirable, if we can call loss desirable: loss with preservation. The ideal example of this is George Washington’s campaigns through New York and New Jersey from 1776 through 1777. In the fall of 1776, Washington’s force of 19,000 militia and Continentals was slowly driven out of New York City. It was not Washington’s finest hour; he lost 3,000 men who were captured because of lack of communications. He was driven from Manhattan, then Harlem, then White Plains, and then withdrew under heavy pressure into New Jersey – that’s how you know it was bad. No one goes to New Jersey voluntarily. By the end of the campaign he had barely 5,000 troops left.

Washington spent the remainder of 1777 successfully not losing, for lack of a better term. He played a masterful ballet with the British, skillfully avoiding a decisive battle where he might have been wiped out. While Washington eventually lost Philadelphia, the British would learn a lesson that Napoleon would learn in Moscow: it is relatively easy to secure a hostile city deep in enemy territory; it is far harder to hold it. And they learned what all the rest of us already know: Philly is not a city worth staying in longer than a few days (Kidding, I love all you Philadelphians). By not risking his army in general battle, Washington set the conditions for successful operations elsewhere – namely, Saratoga – which would bring in foreign aid. This proved indispensable in winning the war for the Continental Army.

Loss with preservation means that you know what to do when you retreat; that there is a plan for a withdrawal; that the force is made to realize that although you may be retreating, you are not doing so out of defeat. It means that the loss can be followed up by a counterattack. It is what the idea of defense in depth is based on: temporary loss of forward positions in order to overextend the enemy and make them vulnerable to a counterattack. It is an incredibly difficult thing to do and must be trained on. A withdrawal can turn into a retreat which can turn into a panic very quickly, unless troops are disciplined and well-led. Tactical withdrawals and disengagements may often be necessary in future conflict, which is why they need to be part of training now.

The next level of loss is a full on retreat. This is best typified by the U.S. Army loss at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Both the U.S. Army and the Confederate armies were amateurs at war and fairly evenly matched. The U.S. Army under Irvin McDowell gained an initial advantage in the attack but overextended and exhausted itself just as the Confederates received reinforcements. Because of the poor or even non-existent training in the U.S. Army which largely consisted of volunteer units made up of 90-day troops, the retreat of some units caused an overall panic that infected nearly every unit on the battlefield. Fortunately, a small rear guard was able to cover the route which staved off total destruction of the army. The Confederates were so exhausted and disorganized from the battle that they were not able to pursue. Whole U.S. units abandoned their position and equipment without even firing a shot.

The worst thing that can befall an army or a unit is full-on destruction. Units are sometimes destroyed for a greater cause: to delay oncoming enemy forces or to seize a vital piece of terrain. Even the dismal performance of the US II Corps at Kasserine Pass in 1943 – a defeat if ever there was one – at least served to delay the Axis advance and buy time for an Allied counterattack. Similarly, the U.S. forces in the Philippines in 1942 fought a sustained action under incredible duress to buy time for the U.S. Navy to recover from Pearl Harbor and return to the Pacific in force. But the destruction of an entire army or large body of troops is far more difficult to justify or recover from. For example, the destruction of Task Force Smith in Korea contributed nothing to the overall situation on the peninsula beyond serving as a wake-up call to the low levels of readiness in the U.S. Army in 1950.

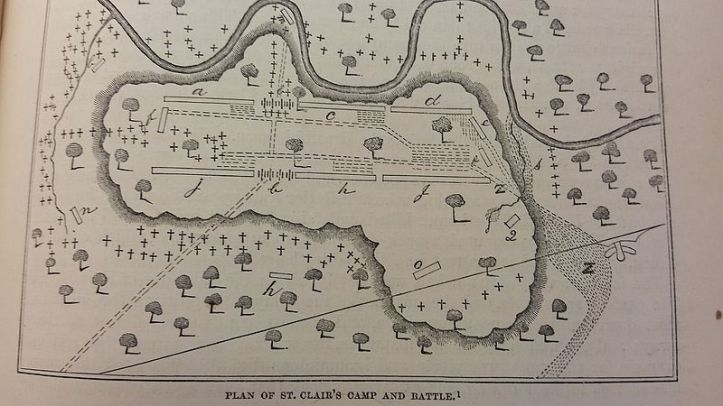

Similarly, the 1791 destruction of General Arthur St. Clair’s Army along the Wabash River in western Ohio was an unmitigated disaster. A previous force of 400 militia and regulars had been soundly defeated near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana, so St. Clair had been sent on a punitive expedition. St. Clair went into the campaign with little intelligence of his enemy – a loose confederacy of western Native American nations – and an insufficient force to wage backcountry warfare. President George Washington urged St. Clair, a veteran of the American Revolution, to move from his base of operations near present-day Cincinnati in the summer months but logistics difficulties and recruitment problems delayed him until the fall. To Washington, alarm bells should have been ringing that this looked all to familiar to the disastrous Braddock expedition into Pennsylvania in 1755.

After three hours of fighting, St. Clair knew that he had to get his force out of there. They attempted one final charge to clear the area to allow for a retreat but as before Little Turtle allowed the troops to pass before returning to strike the flanks and rear. The retreat turned into a rout as the U.S. soldiers fled back to the relative safety of Fort Jefferson several miles away. Losses had been catastrophic. Over 800 Americans were dead; nearly all of the remainder wounded. Enlisted men suffered a 94% casualty rate, making it the worst defeat in U.S. Army history. Half the U.S. Army of the time lay dead or wounded.

Response from the government was swift: St. Clair was forced to resign, Congress began the first special investigation into the conduct of a military action, the regular and militia military forces were strengthened and reformed, and money committed for a full campaign in the west. In other words, much like the defeat of Task Force Smith, it was a wake-up call concerning military readiness. But at a shocking cost of lives lost. Both actions stand as reminders of the hubris of U.S. military leaders and the folly of attempting to project force on the cheap. Separated as they are by 159 years, they share the same causes and the same lessons learned.

Defeat should not be unexpected, nor unlooked for. Leaders who understand that withdrawal is sometimes necessary can preserve their force to fight another day. Which is why it is important to think about and train for a day when we are overmatched on the battlefield. History shows us that the U.S. Army goes into every new conflict unprepared for the new challenges it will face; the lessons learned come with the unnecessary expenditure of lives and equipment. But if we learn to adapt and be accustomed to thinking about loss, we can better preserve the force and situate ourselves for eventual counterattack.

"The lessons learned come with the unnecessary expenditure of lives and equipment." As it always has been, and always will be, because nobody will believe the intel from the other side, nor their capabilities... sigh

ReplyDelete"The lessons learned come with the unnecessary expenditure of lives and equipment." As it always has been, and always will be, because nobody will believe the intel from the other side, nor their capabilities... sigh

ReplyDeleteHey Old NFO;

DeleteYeah, having doubts of ones intel is part of human nature, you can't believe that the other side can screw up like we can.

Great link! Excellent essay.

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing.

I just pointed people your way for this one.

Hey Aesop;

DeleteI just snagged it from "Angry Staff Officer", I have been posting stuff from him for several years. I always add to it but I give him the props and thanks for the plug.