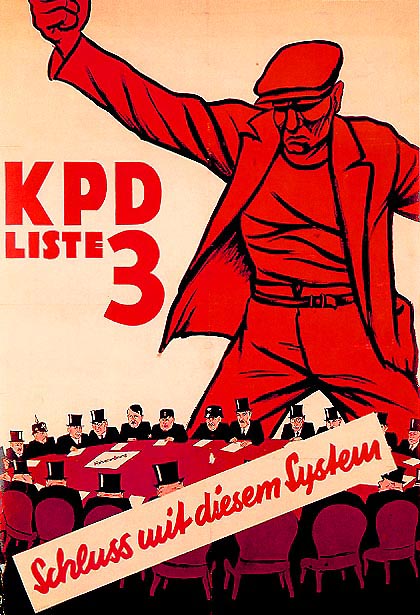

The cooperation between the communist and Nazi parties in Germany to undermine social democracy must be one of the strangest and most extreme partnerships in politics. In the 1920s the Stalinist leadership of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) declared that their main target was the Social Democratic Party (SPD).

The SPD was the dominant political force in the Weimar Republic until the eventual Nazi takeover. In the Stalinist mindset, the only true socialism was Stalinism, and all others were to be opposed. The KPD decided that the way forward in Germany was to do whatever it took to undermine the SPD government, even if this meant working side-by-side with Nazis.

Based on the assumption that the working class would turn to Stalinist communism after the inevitable failure of a Nazi government, the KPD endorsed a referendum to overthrow the SPD government in Prussia. It also supported strikes alongside the Nazis to undermine local SPD power.

Even the KPD’s paramilitary wing, the Roter Frontkämpferbund, often targeted Social Democrats and unions rather than Nazis. Ultimately, this division in the left played a significant role in allowing the Nazis to rise to power. Some Nazi leaders even used it as a tool to drive working-class voters to Hitler.

In the late 1910s, a revolutionary socialist and member of the KPD, named Rosa Luxemburg, supported a revolution intended to overthrow the newly established SPD government. In response, leaders of the SPD worked with a right-wing paramilitary organization in a series of actions that led to her execution.

In the following years, the divide would only deepen as the communist orthodoxy under Stalin was set in place. Stalin’s purges in the Soviet Union are well known, but similar purges happened in Soviet-backed communist parties around the world, including in Germany. Democratic Socialists, Libertarian Socialists, Anarchists, and Trotskyists were all removed from the party. It was under these conditions that Ernst Thälmann would rise to the leadership of the KPD.

Thälmann, like Stalin, believed that a communist revolution was imminent and that social democracy was all that held it back. In fact, the Communist International’s official position was that social democracy formed “the left-wing of fascism.” Thälmann declared that “today the Social Democrats are the most active factor in creating fascism in Germany,” even more than the actual fascists.

Perhaps the most significant example of a “red-brown alliance” can be seen in the 1931 Landtag Referendum in Prussia, where the Communist Party endorsed, at Stalin’s behest, a Nazi referendum to overthrow the SPD government.

Ultimately, the referendum failed to gain enough votes. Nonetheless, other leftists at the time condemned the move. Among the most prominent objectors was Leon Trotsky, an exiled communist from the Soviet Union. He remarked that “In the conduct of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party, everything is wrong: the evaluation of the situation is incorrect, the immediate aim incorrectly posed, the means to achieve it incorrectly chosen.

Along the way, the leadership of the party succeeded in overthrowing all those “principles” which it advocated.” However, these complaints fell on deaf ears, and collaboration between the leadership of the KPD and the Nazis continued.

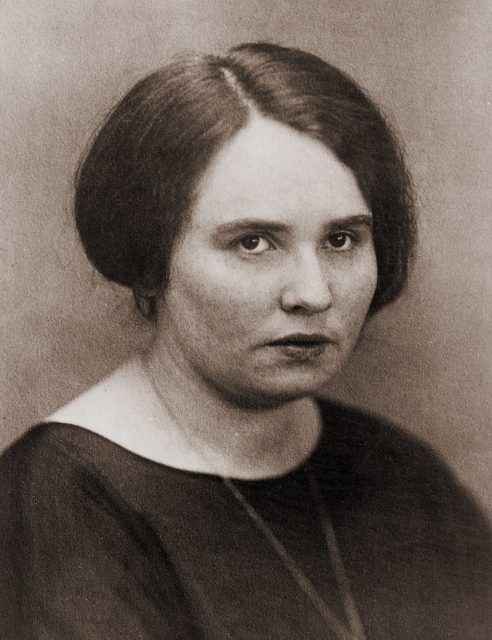

The red-brown alliance was strong in Berlin where it had been a long-standing strategy. As far back as 1923, the leader of the KPD in Berlin, Ruth Fischer, had given a speech to fascist college students and attempted to appeal to them with abhorrent antisemitism, declaring that, “Those who call for a struggle against Jewish capital are already class strugglers… You are against Jewish capital and want to fight the speculators. Very good. Throw down the Jewish capitalists, hang them from the lamp-post, stomp on them.”

Nazis and communists would continue to collaborate. In 1932, on the eve of Hitler’s rise to power, the two factions united to support transportation and rent strikes which crippled Berlin and led to rioting. In some cases, “Communists and Nazis stood arm in arm collecting money for the strike.” The SPD had traditionally maintained a close relationship with labor unions, but on this occasion, it did not support the strike.

At times, the fight between social democracy, communism, and fascism took to the streets in the form of clashes between paramilitaries from each of the parties. Right-wing paramilitary units had existed since shortly after the First World War, often comprised of those veterans who had returned from war and felt that the republic would fail to avenge their loss.

These forces would all come into conflict with one another. There were frequent fights when one organization would try to disrupt the meeting of another. For example, social democracy was generally popular among labor unions, and both the RFB and the SA would attempt to break up union meetings guarded by Reichsbanner troops. Open conflict between SA, RFB, and Reichsbanner members would often break out when any of the parties held a public rally.

In some instances, SPD and KPD members joined together to form neighborhood and shop-floor alliances, and even formed the original Antifa together. Another example is the SPD trade union members who participated in the Berlin strikes, despite the Social Democrats’ official opposition. There were times when the average worker was clearly more aware of the dangers of Nazism than their leaders were.

The failure to form a government set off a series of elections every few months until the Nazis, through the use of violence, eventually won enough seats to form a government.

When the Reichstag met to pass the Enabling Act that would grant Hitler the powers of a dictator, SA stormtroopers swarmed inside and outside the building to intimidate any potentially reluctant moderate representatives. The KPD’s representatives had already been arrested or fled into exile.

Abandoned by their moderate allies, the Social Democrats stood alone against the Act, providing all 94 votes against it. With 444 votes in favor, democracy had fallen while the left devoured itself. The KPD, and shortly after the SPD, were banned, and so the Third Reich began.

My father, Bernhardt, lived through it. Born in 1921, a boy, a Hitler Youth, an apprentice steam engineer in the German merchant navy, a conscript in the Reichsmarine until a British cruiser ended that, a POW in the UK and Canada.

ReplyDeleteHe's dead now, but he and my aunts and uncles told me enough.

My Opa and namesake, "Fritz", Bernhardt's father, got machine gunned by the Canadians in WW I and survived. I didn't meet him until I was 10. He laughingly told me, as he plied me with Dunkelbier, that he held no grudges and the Canadians were marvelous troops except for their weakness for booze.

Lord love them all.

And to Hell with Nazis and liberals. But I repeat myself. And my father.