Map of Divided Berlin that hangs in my bonus room.

In 1962, an American news producer

struggling to find stories about East Berlin escapees decided to create

one. Rumors of a tunneling attempt that had run low on funding reached

an executive at NBC News, and it was decided that the best way to get

their big scoop would be to fund one themselves.

East German leader Walter Ulbricht had

spent a long time urging the rest of his party for a wall to be built in

order to stop their country from hemorrhaging large numbers of people

to the West. In 1961, he got his wish and began making plans away from

public scrutiny.

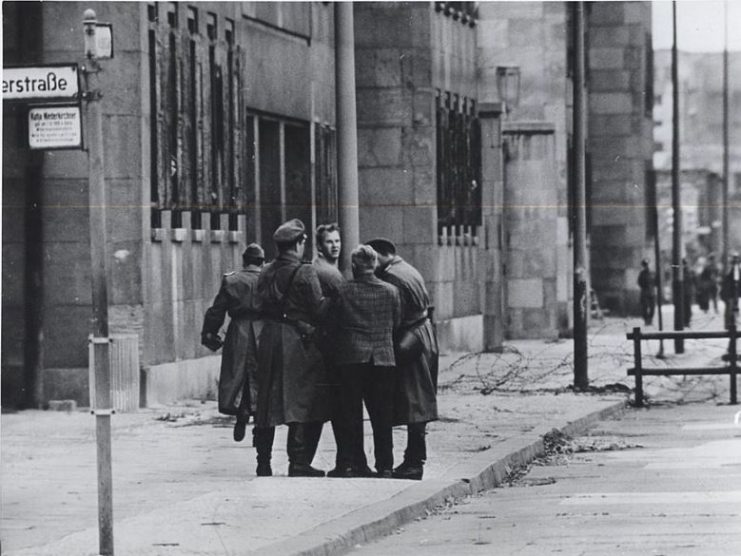

The Berlin Wall went up almost overnight.

On the morning of August 13, 1961, East and West Berliners were left

scratching their heads as they peered past the barbed wire and beyond

the East German soldiers guarding the border. By the end of the first

day, almost all the gaps were sealed, and the fate of those trapped on

one side or the other was all but decided.

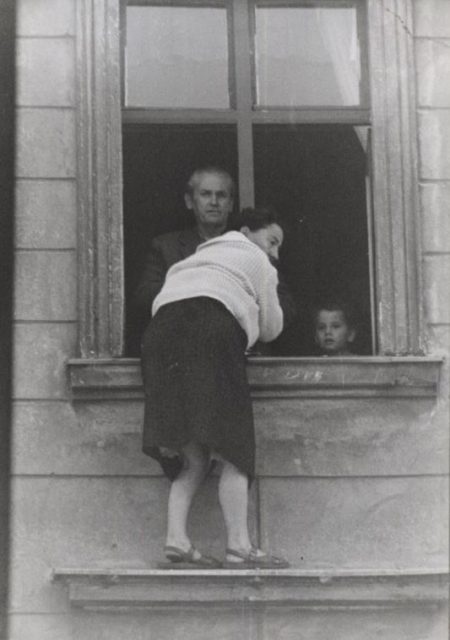

Families were separated. Jobs held in the

West by those living in the East were lost. Houses bordering the divide

had their windows bricked up.

In the early days of the wall, there were ad hoc

escape attempts, such as vaulting the barbed wire or jumping out of

windows. Some were successful, but the GDR’s (German Democratic

Republic) violent reactions to these attempts quickly set an example for

any future endeavors. From then on, meticulous planning would be

required if anyone wanted to escape.

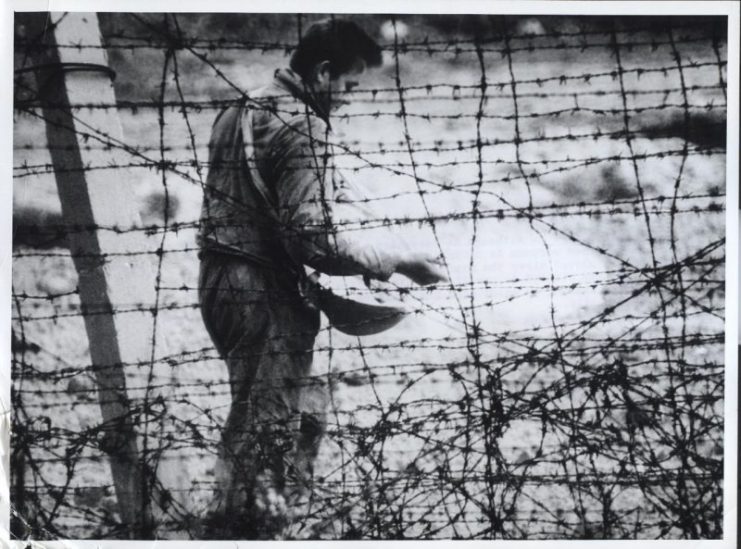

Late

August 1961. A worker spreads chemicals to kill weeds and to provide a

clear line of fire for the East German guards watching the border for

anyone seeking to escape to West Berlin

Late

August 1961. A worker spreads chemicals to kill weeds and to provide a

clear line of fire for the East German guards watching the border for

anyone seeking to escape to West Berlin

The 1960s saw a high number of elaborate

escape plans. The wall was still a fresh wound, and the idea of

reuniting families and friends was a popular idea — not just in Berlin,

but internationally.

News companies from all over the western

world were desperate to obtain images of escapes. Often, the cameras

arrived only in time to capture the reuniting of loved ones. The escape

attempts themselves had to be kept secret as nearly one in six East

Germans were working for the Stasi (secret police).

“I’ve got a tunnel,” journalist Piers

Anderton said as he walked into the office of executive producer Reuven

Frank at NBC. Anderton had made a connection with a group of German and

Italian students determined to save whoever they could from the East.

Choosing the basement of a West Berlin

factory, the students had begun to dig the 100 yards necessary to reach

the East. But they lacked funding and, consequently, were short of the

necessary tunneling materials. The clay earth had proved treacherous and

the collapse of nearby tunnels, as well as the near deaths of friends, had indicated that this was a job to be taken seriously.

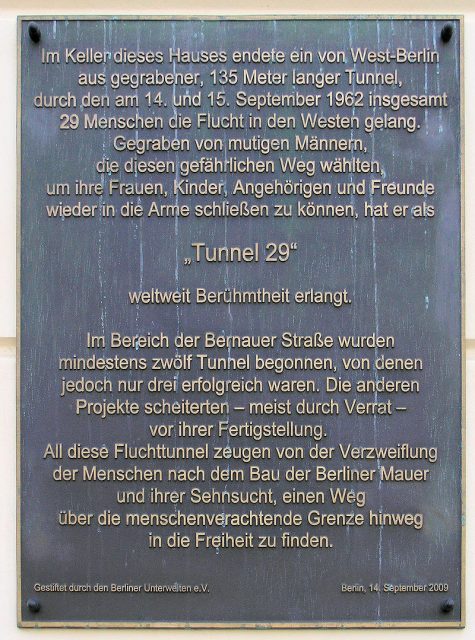

Tunnel 29 cost NBC around 50,000

Deutschmarks (about $150,000 in today’s money) and was dealt with

“outside the NBC channels.” Only the small Berlin team, the NBC News

president, and his assistant knew of the details: no lawyers, no

politicians.

The secrecy was, in part, an attempt to

hide the planning from Eastern ears. However, the most pressing matter

was East-West relations. The risk of potentially sparking an

international crisis would have certainly been acknowledged by those in

the know at NBC News.

Seeing it as a humanitarian investment as well as a “big scoop,” the news channel decided to continue regardless.

Using this new injection of money, the

team was expanded to 40 tunnelers. Tools and food were purchased, and

underground rest areas were built to house the workers. Sending a camera

team down the pit, NBC News began obtaining images unlike anything

previously seen.

Speaking in a German language interview in 2001, one of the tunnelers, Joachim Neumann, spoke about the digging of Tunnel 29: “We

sometimes housed in there, like in barracks, for one or two weeks at a

time. We wanted to keep the traffic in-and-out down to a minimum, so we

slept right there instead of heading home after each shift.”

Aiming for two meters per day, they were

to dig continuously by rotating day and night shifts with four to five

people per shift. The 40 tunnelers would take it in turns.

“[We] had a real shift schedule so that

everyone knew when and where he was assigned to work and if he couldn’t

make it one time he had to find a substitute,” Neumann said.

In a world of spies and informers, the tunnelers were naturally suspicious. The team leaders secretly changed

the tunnel’s exit location, and a code was established. And they were

right to do so. Little to their knowledge at the time, one of the

diggers was an East German secret agent, remember the 1 in 6 Osters spied on the others..? Fortunately, he was kept in the

dark regarding the location change.

On the surface, escape attempts

continued. Peter Fechter, an 18 year old East German, dashed over the

wall before being gunned down by border guards. His photo was pinned to

the tunnel’s entrance as a reminder of why they were working so hard.

Once the tunnel was ready in late

September 1962, NBC News broadcasted a series of coded messages, and the

escape attempt was set to go.

News cameras at the ready, the East

German refugees began to appear. One woman wore a Dior dress so that she

could look her best when entering the affluent West. One man tearfully

embraced his wife and baby who had been waiting for him for over a year.

Another escape trip was attempted, but it

was to be the last. The wet clay and a series of leaks forced the

closure of Tunnel 29. Only on its collapse did the Stasi uncover the

true exit of the tunnel.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I had to change the comment format on this blog due to spammers, I will open it back up again in a bit.