I had blogged a bit about the CSS Virginia the best known of the Confederate Ironclads, the confederacy used a myriad of ships to turn into ironclads to challenge the Federal navy

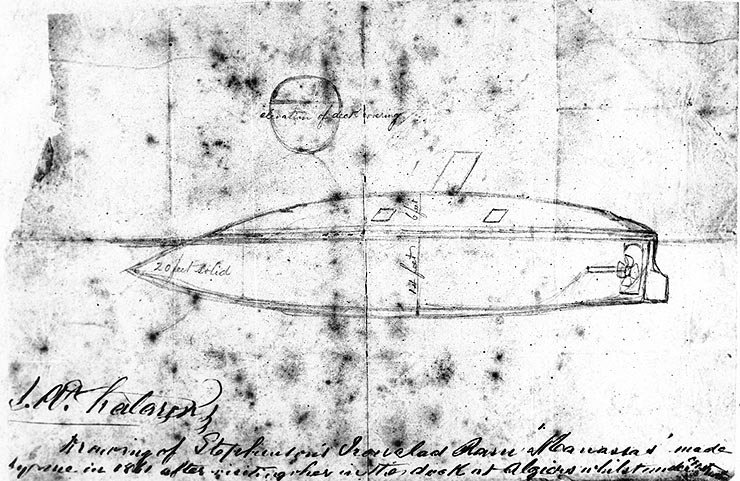

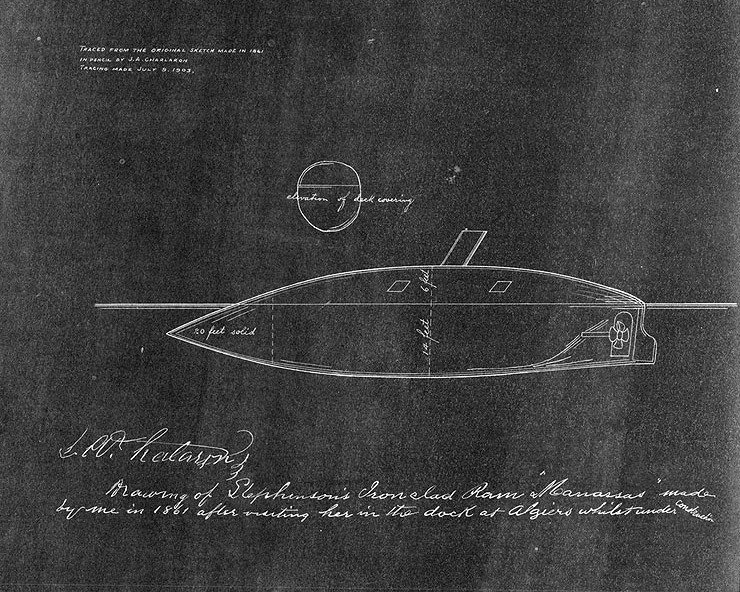

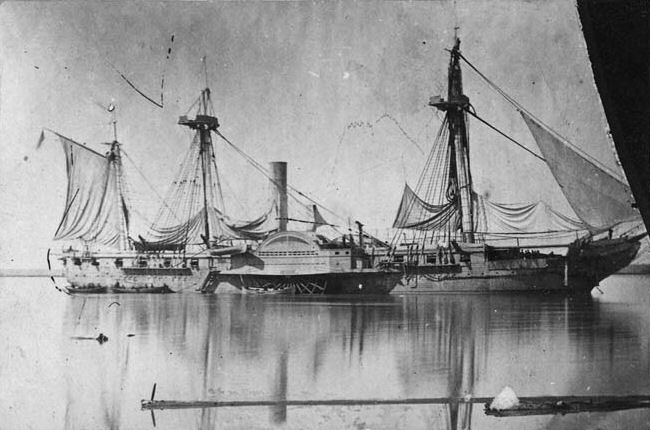

C.S.S Manassas

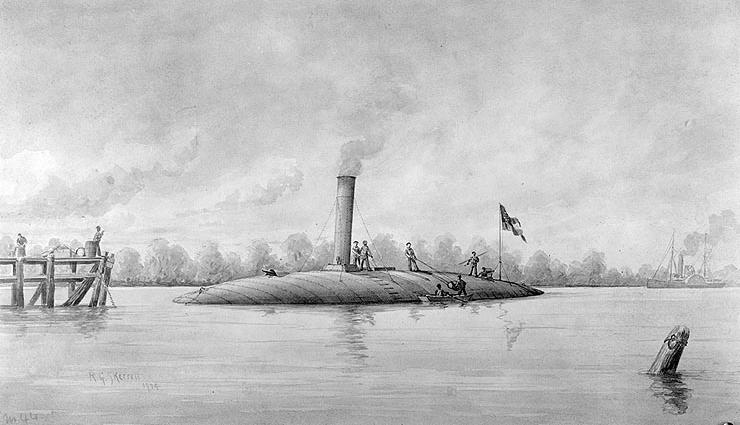

From the very onset of the Civil War, the Confederacy knew they were overmatched by the industrial might of the Union. The Union Navy operated with near impunity along the shores of Confederate territory. Seeking a way to challenge this mighty foe, the Confederacy tried many new and unconventional tactics. In addition to boobytraps and privateers, the Confederacy was also mindful about the recent emergence of ironclad warships. At a time when a majority of navies were made up of wooden sailing ships, the ironclad seemed like an invulnerable beast, able to decimate fleets of wooden warships with impunity. Thus, the Confederate Navy attempted to bolster its fleet with numerous ironclads. Though many were completed and several went on to make a name for themselves, none were as radical in appearance than the CSS Manassas. Her very appearance was enough to have Union forces describe her as a “Hellish Machine”

Outside of her radical armor, the ironclad was modest. A smaller ship, she was only about 128′ in length with a beam of 26′ Intended to operate from the Mississippi, the ship’s draught was reduced to 11′. She was steam driven, propelled through the water by twin screws. Only one gun was equipped, a 64-pounder. The gun could only fire forward and was protected inside the hull by a large armoured shutter. However, this gun was only a secondary armament as the primary weapon was a ram jutting out from the ship’s stem. With her armor, it was expected that the ironclad could steam into the fray and ram opponents at her leisure.

When construction was completed, the ironclad was commissioned on September 12, 1861 as the privateer Manassas. Unfortunately for the investors behind Manassas, they would never get to enjoy the fruits of their labour. George R. Hollins, commadore of the small Confederate fleet tasked with protecting the lower Mississippi, was desperate to bolster his meager fleet. Aware of the construction of the Ironclad, he ordered a crew to seize control of the ship. Following her commissioning, the ship was immediately appropriated by the Confederate Navy as the warship CSS Manassas, the first Ironclad to enter service with the Confederacy. Hollins was aware of powerful Union warships gathering in the lower Mississippi and it was hoped that the radical ironclad would be enough to balance the scales. Manassas would be put to the test during the Battle of the Head of Passes, a mere month after she was first commissioned.

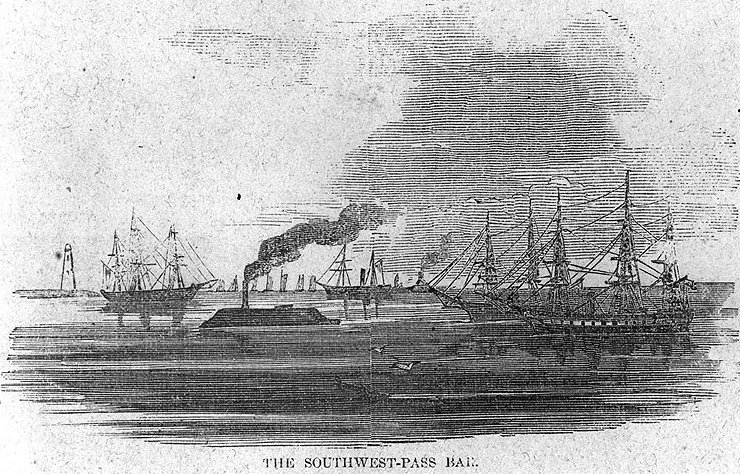

As part of the Union blockade strategy, the crucial Confederate port of New Orleans was a priority target. Due to its location on the Mississippi River, the Union fleet only had to block the river’s mouth to effectively cut the Confederacy’s largest city off. The problem was that the Mississippi river branched off into three different directions as it emptied into the Gulf of Mexico. This area of divergence was known as the Head of Passes and it allowed Confederate ships to circumnavigate the Union warships. To secure this strategically important location, the commander of of the Mississippi blockade squadron, Captain William McKean, dispatched four warships under Captain John Pope to secure the Head of Passes and establish a fortication.

Commodore Hollins could not allow the Union to control the Head of Passes. The area would provide the Union with a perfect position to launch an invasion fleet upon New Orleans. He had to launch a preemptive attack before more Union Warships arrived or the fortification was completed. Thus, he took control of the Manassas and marshalled the rest of his fleet At his command, Hollins had the ironclad Manassas and six small gunboats, Calhoun, Ivy, Tuscarora, McRae, Pickens, and Jackson. On October 12, 1861, the tiny Confederate fleet moved out before dawn and headed downriver with Hollins commanding from Calhoun.

Hollins organized his fleet with Manassas in the lead. She would carry out the opening attack by ramming the anchored Richmond. Once Richmond was crippled, the Confederate gunboats would deploy three fire rafts to drift downriver. The rafts were chained together and it was hoped that they would ensnare the Union Warships. Though it was possible for the Manassas to be caught by these fire rafts, Hollins was willing to sacrifice his most powerful warship if it meant the destruction of the Union fleet. Hollins would wait behind with his gunboats, waiting for the opportunity to mop up the remaining enemy forces.

As Manassas steamed downriver to engage the ships, she picked out Richmond and began accelerating. She was spotted by Preble, anchored ahead of Richmond. The warship promptly opened fire on the interloper. However, all of her rounds sailed over Manassas and the Confederate Ironclad continued on her collision course. In the darkness, she was barely visible and only the sparks from her stack stood out. No doubt, the crew of the Union warships were bewildered by this fire-belching contraption as it bore down on the seemingly helpless Richmond. Her aim true, Manassas crashed into the side of Richmond. However, it was at this point that everything went to hell.

Unknown to the Confederates, the coal barge Joseph H. Toone was tied alongside USS Richmond. As Manassas rammed the Union ship, she also collided with the barge, lessening the impact. Though Richmond was damaged, she was in no danger of sinking. Manassas came out considerably worse. The impact knocked one of her engines loose, cutting her power. In addition, it caused her hull to buckle, allowing water to enter the hull. To make matters worse, the momentum of Manassas carried her along the hull of the Union warship and she briefly became trapped between the warship and the barge. Luckily, the impact caused the Toone to break away from Richmond and, in the process, free Manassas.

Free, but damaged, Manassas turned away and tried to escape upriver. She fired off rockets to signal the deployment of the fire rafts. (One rocket was knocked over and ended up shooting inside the Ironclad, ricocheting about inside.) As Manassas made her escape, Union gunners began finding their mark and one managed to knock the ironclad’s stack off. Luckily for the damaged ironclad, the arrival of the fire rafts and shelling by the gunboats caused the Union ships to panic. Cutting their lines, the Union warships retreated downriver. Manassas continued moving upriver while the gunboats pursued the fleeing Union fleet. In the confusion, the Union ships ventured out of deeper water and all warships except Prebel grounded themselves on a river bar. However, they still exchanged fire with the Confederate gunboats and by ten o’clock that morning, Hollins decided to pull back. Taking the damaged Manassas in tow, the victorious Confederate fleet sailed back to Fort Jackson.

In the confusion of the battle, the Union Navy appeared to have placed more blame on Manassas than their own ineptitude. The sudden appearance of the alien-looking craft ingrained itself on the Union fleet during the battle. John Pope wrote back to his superiors, stating that, “Everyone is in great dread of that infernal ram. I keep a guard boat out upriver during the night.” [1] Over the next couple of months prior to the Battles of Fort Jackson and St. Philip, the Union Navy continued to fear the strange ironclad guarding the Mississippi River.

In stark contrast, the Confederacy was tremendously disappointed by the Manassas. Though she was intended to sink Union warships with impunity, she emerged from the battle as the most damaged warship. She proved to be too lightly built for her intended role. In addition, she was too slow to keep up with Union warships. Even the sailing vessels were able to outrun Manassas as they retreated downriver. Her turning radius was also horrible, preventing her from effectively using her primary weapon. Despite her ineffectiveness, the Confederacy was so short on warships, she was officially purchased within two months.

One month after the battle, the Union Navy began developing plans to assault New Orleans directly. As the largest city in the Confederacy, capturing it would deal a fatal blow. While the Confederacy had originally devoted numerous resources towards the defense of the city, the deteriorating war situation led to the slow removal of resources so they could be sent elsewhere. New Orleans lost many of their defensive guns and soldiers. The primary defense of the city was soon left to the Confederate fleet and two forts downriver of the city named Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. Manassas and the rest of the Confederate fleet were kept at the ready for the next several months until the following Spring when the Union Fleet began making their move.

Commodore Hollins, though renowned for his heroic victory at the Battle of the Head of Passes, could not impress upon his superiors the danger that New Orleans was in. Once he heard reports that the Union Navy was in the process of moving its ships into the Mississippi River, he attempted to get permission to launch another preemptive attack on the Union while they were vulnerable. Instead of getting permission, Hollins found himself recalled to Richmond. Command of the Confederate fleet fell to John Mitchell, a considerably less capable leader. To make matters worse, the Confederate Navy and Army could not agree on how to command their forces. By April 18 1862, the Union Warships under Commodore David Farragut were moving upriver and the Confederates had to go into battle with their piecemeal forces.

From April 18 to April 24, the Union Navy attempted to use mortar ships to bombard forts Jackson and St. Philip into submission. However, following the ineffective bombardment, Farragut decided to simply run the gauntlet and invade the city directly. At 3:00 am, the Union ships arranged themselves into formation and began heading upriver. The Confederate warships arranged themselves just behind the forts, ready to attack the Union fleet at first light.

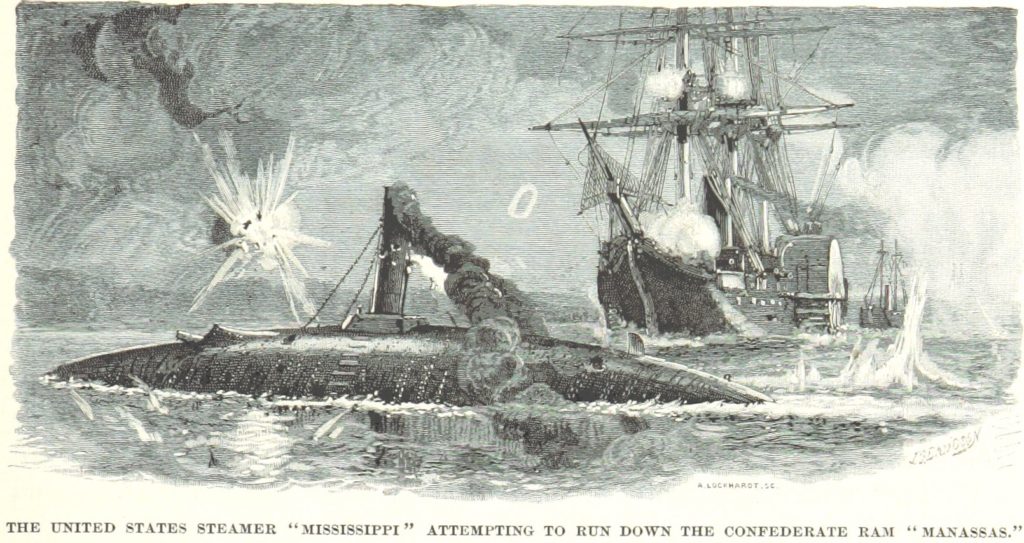

Once safe from friendly fire, Manassas positioned herself for a run on USS Pensacola. As she approached the ship, the larger Union ship avoided the attack and fired upon the Ironclad. However, the broadside was ineffective and Manassas continued fighting. She next spotted USS Mississippi and accelerated. She managed to ram Mississippi, but her momentum caused her to scrape along the hull of the Union frigate. She did manage to fire a round into the Union ship, dealing minor damage. She then attacked the sloop of war USS Brooklyn. Manassas rammed Brooklyn and fired into the ship, inflicting serious damage though ultimately not fatal.

Interesting piece of history! Thanks!

ReplyDeleteHmm - i wonder if Clive Cussler could find her wreckage, if any of it still exists.

ReplyDelete