The Battle of Bunker Hill or actually Breeds Hill but Bunkers Hill was the first large scale engagement between the British and the Colonist, who were still considering themselves part of the British Empire, the Declaration of Independence wasn't mentioned until July 4 1776. At this time Many were hoping that King George III and his ministers would see reason and back off on their unreasonable demands, but they doubled down and the die was cast.

On May 25, 1775 – as gulls squawked, circling overhead – the British frigate HMS Cerberas dropped anchor in Boston harbor. Onboard, generals William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne prepared to disembark after a lengthy trans-Atlantic passage. It would not take them long, however, to discover that his majesty’s forces and his colonial subjects were now locked in a virtual state of war around Boston, and that the colonists had seized control of all land access to and from the city.

Unbeknownst to the three generals, they had just dropped anchor in Chapter One of the American Revolution.

Relations between the Province of Massachusetts Bay and Great Britain had been spiraling downhill for quite some time. In response to a series of taxes and import duties placed on the colonies, in December of 1773 members of the Sons of Liberty boarded British merchant ships in Boston harbor, and dumped tons of tea into the water.

The king’s response to the Boston Tea Party had been the introduction of 4,000 British regulars into the city under command of General Thomas Gage, who had orders to promptly restore order.

But things did not go well, and in 1775 Gage found it necessary to close Boston’s port to merchant traffic, a punitive measure that caused both a serious financial and political crisis in the city. Then relations grew worse, and local militias began stockpiling weapons in various country locations.

On April 19, 1775 Gage sent a force of 700 regulars on a mission to collect or destroy what armaments and supplies they could locate in the villages of Lexington and Concord.

Local militias were promptly notified and gathered to oppose the British advance. Early that morning the first shots were fired at Lexington Green, and later a detachment of about 100 British regulars faced a determined collection of militias numbering about 400 at Concord Bridge. Shots were again exchanged, and the regulars, clearly outnumbered, began withdrawing toward Boston.

Additional militias then joined in the pursuit, and a running gunfight between Americans and Redcoats roared back-and-forth throughout the afternoon, all the way back to Boston. The militias then swarmed the city, cutting off land access. Since then, the British garrison had been reinforced by sea, increasing their numbers to approximately 6,000, but they remained besieged within the city’s limits.

This, then, was the basic situation as the Cerberas dropped anchor on May 25. Except that in the intervening month, militias from across New England had descended upon Boston like swarms of angry hornets, swelling the ranks of the encircling Americans to somewhere around 15,000, all of them now under command of General Artemas Ward. But angry militias are no more an army than are angry hornets, and while the colonists surely outnumbered the British, they lacked even the basics of organization, supply, and discipline required for effective campaigning – all significant shortcomings.

Now well reinforced, and with the addition of three major generals for assistance, Gage began plotting a breakout. The British officer’s opinion of their American besiegers at the time was decidedly low, and this disdain certainly played into their planning.

Typifying this attitude was General “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne, who considered the Americans little more than a “rabble in arms.” Overconfident of success, he told Gage, “Ten thousand peasants keep 5,000 king’s troops shut up! Well, let us get in and we’ll soon find elbow room.”

The plan the generals devised was first to take back Dorchester Neck, south of Boston, then move upon Dorchester Heights, ultimately attacking the American militias occupying nearby Roxbury. Once that phase had been completed, the Redcoats planned to move on Charleston Heights and Cambridge simultaneously, shattering the American’s grip on the city. Execution of the plan was scheduled for June 18.

But a New Hampshire gentleman, visiting Boston, had gotten wind of the plan, and the news was promptly relayed to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. The Congress then ordered General Ward to erect appropriate defenses, and Ward directed General Israel Putnam to fortify Bunker Hill, a prominent elevation on the Charlestown Peninsula, just north of Boston.

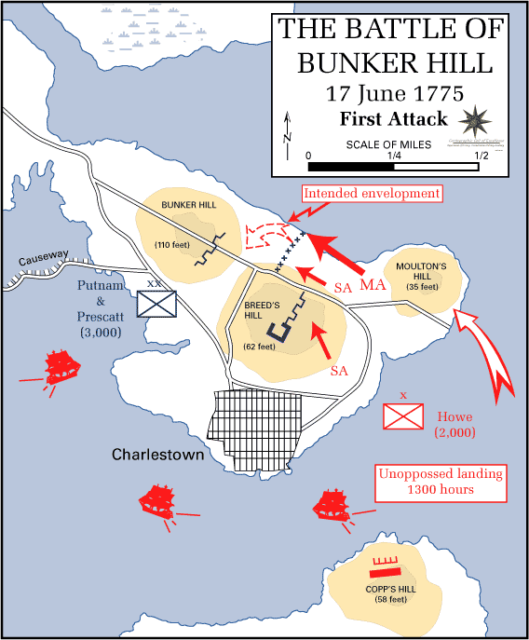

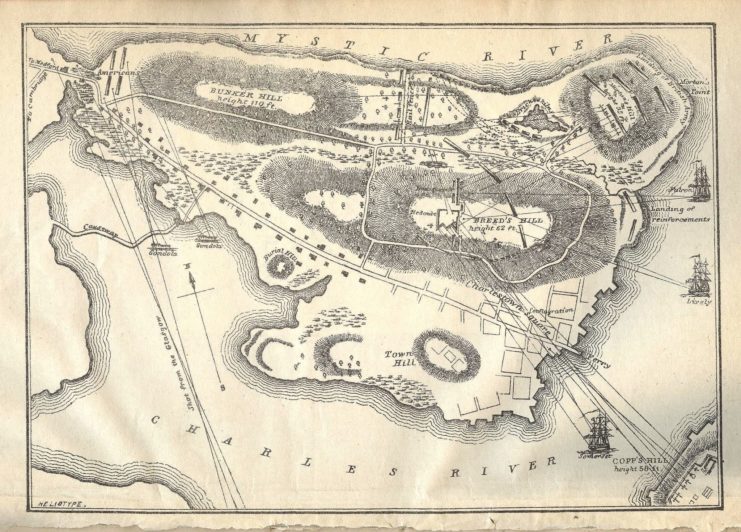

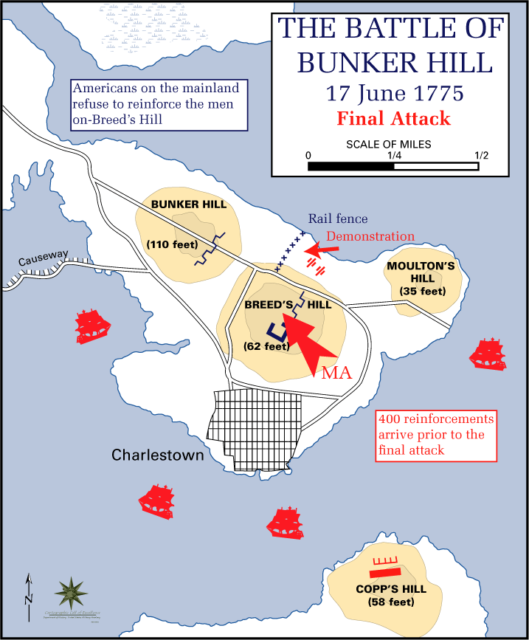

During the evening hours of June 16/17, Colonel William Prescott, in command of several militia forces totaling about 1,200, began to erect the called-for fortifications. Some initial work was done on Bunker Hill, but the focus then shifted (for reasons still unclear) to Breeds Hill, which was lower, but closer to Boston than Bunker Hill. A square redoubt was constructed, about 130’ per side, with a firing platform erected inside.

This work-in-progress was quickly discovered by the British, however, and early the next morning their batteries opened-fire on the redoubt; but causing little in the way of damage. Watching as the fortifications were going-up, the British generals decided to immediately mobilize an attack against the Americans, both Howe and Burgoyne of the opinion that their troops would easily sweep over the “rabble” and put them at once to flight.

It would take the British hours, however, to accumulate the necessary force, and then additional time to ferry them across the water to the Charlestown Peninsula. At last, with the arrival of their marines, the British had finally amassed a force of 3,000 on the Peninsula, sufficient, it was thought, to disperse the colonists.

These British preparations hardly went unnoticed, however, and the Americans responded by marshalling additional men and hastily throwing-up fortifications across the width of the Peninsula. By 3 o’clock that afternoon, just as the British launched their initial assault, the American force had swelled to 2,400, manning a string of defenses of varying complexity.

But the American forces, while game, were in a state of disarray, still a conglomerate of militias with no real central planning, communications, or coherent leadership. Nevertheless, as time would tell, those individual militiamen who had come to the Charlestown Peninsula that day, had come to fight.

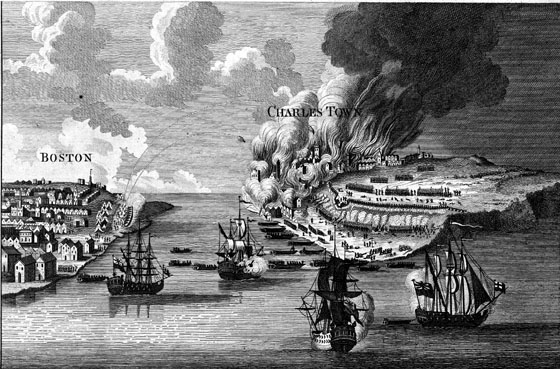

Taking fire from buildings in Charlestown on their left, the British opened the engagement by lofting artillery rounds into the town, then sending in troops to set fire to the buildings. As great, black funnels of smoke rose from the village, Howe – in field command, a servant at his side with a bottle of wine for his refreshment – sent a feint at the redoubt on Breeds Hill, while launching his major assault on the American left.

This attack was meant to dislodge the militia line established in front of Bunker Hill, then sweep behind the Americans on Breeds Hill, effectively cutting-them-

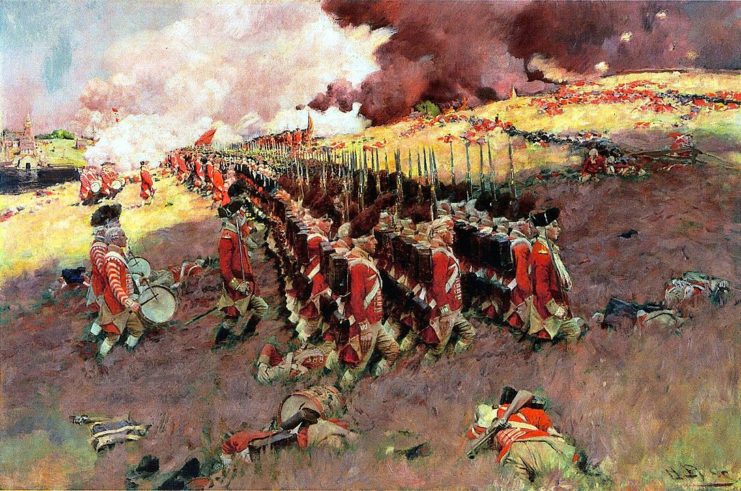

The assault on the left was led by Howe himself, and was comprised of both regular infantry and grenadiers. When the files of Redcoats marched into musket range, an unexpected explosion of smoke and fire erupted from the colonists positioned behind a line of rail fencing, instantly savaging the British ranks.

The Redcoats returned fire but, under a fusillade of accurate musketry, were forced to withdraw in some confusion. This, to say the least, was not what Howe or his officers had expected.

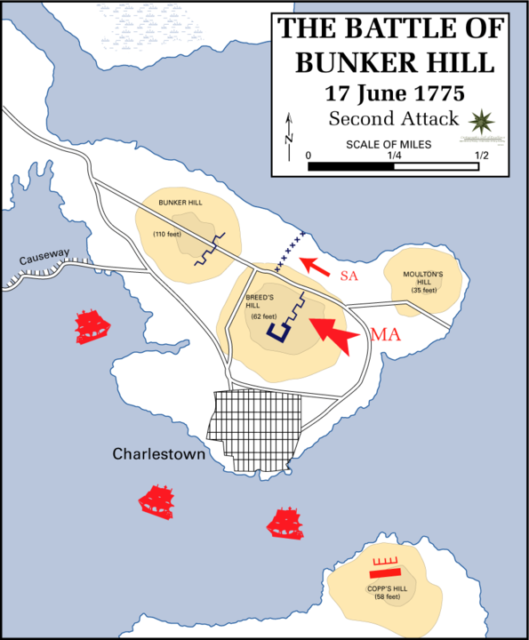

The British regrouped for a second try. This time Howe sent his troops on Breeds Hill directly at the redoubt, while he led another assault on the American left. Both attacks were handled roughly by the Americans, British troops gunned down in ghastly clusters before being forced to withdraw once again.

British losses were already appalling. “Most of our Grenadiers and Light-infantry,” said a British officer, “the moment of presenting themselves lost three-fourths, and many nine-tenths, of their men.”

While the American defense had held against both attacks, behind the colonist’s lines something approximating chaos reigned. General Putnam tried to shift troops to the endangered points, but his grasp of the battle, his troops, and British intentions was limited. Moreover, the American units remained disorganized, some following orders, some fighting on their own hook, others making for the rear.

With no true chain-of-command, the American’s response was precisely the jumble of confusion that had exemplified their siege since its inception. While individuals fought with great valor and distinction, tactical coherence, at the time, remained beyond their organizational capabilities.

Meanwhile, the British, although twice mauled, rose valiantly for yet another attempt at the American works, this time directed essentially at the redoubt on Breeds Hill. Initially, this assault appeared equally as doomed as the two that had preceded it – Redcoats tumbling in great numbers before volleys of musketry – but soon the American defenders ran out of powder and, with that, their defense quickly imploded.

No longer able to hold the British advance at bay with musketry, the combat – as Redcoats poured into the redoubt – became one at close quarters, even hand-to-hand, the sort of fighting the British – trained fighters, armed with bayonets – were far more proficient at than the colonists. Fighting in the redoubt became desperate, soon hopeless, and the Americans were forced into retreat.

But the British, now hoping to drive home a decisive victory, were denied the opportunity of maneuver by a sensibly conceived and disciplined American withdrawal. While the American retreat was rapid, it never devolved into pandemonium, what might well have been expected from such a disorganized assemblage of militias. Despite leaving much artillery, ammunition, and tools on the field, most of the American defenders crossed over the Charlestown Neck in good order, later to redeploy at Cambridge.

Thus were the British left in command of the field, claiming a hard-won victory as a result, but it was a Pyric victory at best. British dead and wounded lay in mangled rows across the field in numbers far beyond what any of their commanders had ever imagined possible, the Charleston Peninsula a measly prize for the carnage.

The colonists had reformed elsewhere (as they would throughout the war), and, at days end, the cost suffered for moving them a few miles appeared wildly disproportionate to the price paid for moving them.

The British had suffered 1,054 casualties: 226 dead, 828 wounded. While those counts do not appear high by today’s modern standards, they were horrific by 18th Century norms, especially when compared to the “rabble’s” approximately 140 dead and 310 wounded, most of which were suffered during the retreat. It was one of the worst days for British arms during the entire course of the war.

Moreover, it was the British officer corps (commissioned and non-commissioned) that paid a particularly heavy price for the afternoon’s bloody adventure. In European warfare, where the officer corps were generally aristocratic, firing deliberately at officers in the field was unacceptable. But the Americans, untrained in the ways of Continental warfare – and watching as officers led their troops forward – were more-than-happy to gun them down.

Howe’s staff had been decimated, and the total included 100 dead and wounded commissioned officers, a significant percentage of their entire North American corps. At day’s end, the mood among the British generals was decidedly somber. Clinton later wrote: “A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America.”

The lessons drawn from the battle varied for each side, but each, in their own way served to lengthen the course of the war. The British, quite correctly, were forced to reevaluate (somewhat) their earlier dismissive attitude of American fighting capabilities and – with limited troops and an even more limited corps of officers – think twice about of launching costly frontal assaults against entrenched positions.

Howe, in command of the American campaign after Gates was recalled, became notorious for the almost glacial pace of his movements, and the specter of Bunker Hill has often been raised to account for this lack of zeal. Unfortunately, the British high command never lost entirely its scorn for the American fighter, a self-inflicted miscalculation that hobbled their war planning throughout the conflict.

The Americans, on the other hand, became convinced that Bunker Hill was proof positive that properly inspired militias could whip the British, and that a professional army was therefore uncalled for. While George Washington – the newly appointed commander of the “army” at Boston – knew otherwise, it would take him years to convince many in Congress to the contrary. Hence the war was delayed at its inception by these two interpretations and would ultimately drag on for six long years.

But surely the most salient lesson to be gleaned from Bunker Hill was the fact that the colonists – while unquestionably disorganized, untrained, ill-supplied, and undisciplined – had nevertheless mauled two splendid British advances and, had their powder not runout, may well have inflicted a disastrous defeat on the king’s troops by day’s end.

That their powder did run out provided the British with victory, but that victory could in no way erase the fighting spirit displayed by individual American militiamen. “Our three generals,” a British officer later lamented, “expected rather to punish a mob than fight with troops that would look them in the face.”

Thus, as the smoke cleared late that June 17th – and as the British gathered their dead and wounded from the downslope of Breeds Hill – generals Clinton, Howe, Burgoyne, and Gage, may well have wondered if their collective futures now held something far more unpleasant than any of them had before considered.

For if American militias continued to fight with the same spirit and fury, the war in America might prove considerably more difficult, bloody, long, and potentially ruinous, than anyone on the other side of the Atlantic had ever dreamt.

On June 17, 1775, the rabble had risen seemingly en masse, and on a single furious afternoon had written an emphatic, almost deafening statement of collective resolve. Only time would tell if that statement was simply a fleeting aberration – a passing wisp of high passion – or something far more ominous.

A lot of history here I either never learned, or long ago forgot. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteHey Doug;

DeleteLong time no see, glad to see you are still around. And you are welcome.