I recall this raid in my history, my specialty in the Army was ELINT, the British were having a battle with the Germans over Radar. Radar stands for RAdio Detection And Ranging. The Germans were using Radar beams to guide their bombers over targets in England and the British were working countermeasures, also the Germans were using Radar to identify the British night raids that were trying to attack the German homeland at night so it was turning into a war of technology, the first of its kind.

Parachutes and radar are long-established elements of war. But they both came into their own with Operation Biting. This British raid from the skies took place on the 27th February 1942.

Brave men landed in the northern French commune of Bruneval with the aim of stealing Nazi radar components. They faced incredible odds but came out the other side in triumph.

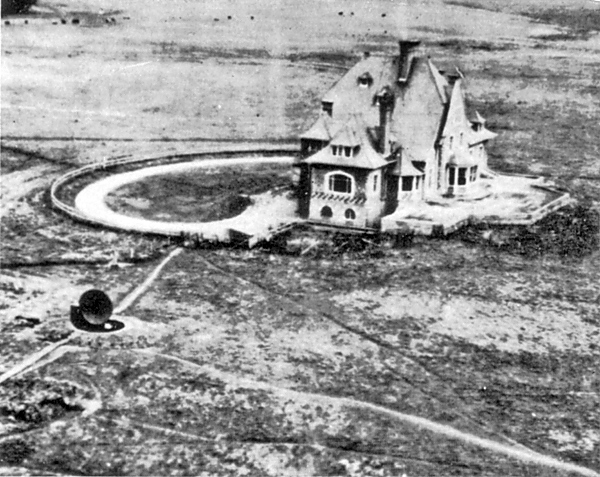

The Germans had set up a radar installation called “Wurzburg”, which Churchill’s experts wanted to get their hands on. At the time an invisible conflict was going on; “The Battle of the Beams”

As described on the Combined Operations website, the game was to jam your enemy’s kit so they didn’t see you coming. Radar expert Dr Reginald Victor Jones was in charge at the British end.

Lord Mountbatten set the plan for Operation Biting in motion. The lead up to the mission had been perilous in itself. Resistance operatives risked their lives gathering intelligence on Bruneval’s beachside location. Photographs of the target were taken from a Spitfire. This was way before the days of cameraphones, so the pilot really needed to master the art!

The recently-formed 1st Parachute Brigade, 2nd Battalion C Company were assigned to the momentous task. They’d been in existence only a matter of weeks. And reaction to their involvement wasn’t exactly positive. As Bruce Crompton explains on his ‘Amazing War Stories’ podcast, “Many in the corridors of power thought the Parachute Forces were a folly, a drain on vital war resources. However Churchill was determined…”

Commanded by Major John Frost, the team were assembled and trained rigorously in (typically co-operative!) British weather. High levels of secrecy were maintained.

As described on the Combined Operations website, the game was to jam your enemy’s kit so they didn’t see you coming. Radar expert Dr Reginald Victor Jones was in charge at the British end.

The men had to fly at night. Yet they remained in the dark over what exactly they were doing. Combined Operations writes, “The parachute unit, for example, believed the War Cabinet wanted them to demonstrate techniques and capabilities for raiding a headquarters building behind enemy lines.”

The Brigade, comprised of 120 men, were traveling by Whitley bomber. They would be dropped 600 ft. The drop was straight through the floor, with a risk they’d receive bumps and bruises before they even left the plane! The men were expected to display ABI, or “Airborne Initiative”, meaning no matter how bad thing got, they did their duty.

Once on the ground they operated in 3 sections. One to take the beach, another to serve as rearguard and reserve. Flight Sgt Charles Cox was part of the third group, who were responsible for raiding the Wurzburg. Offshore was Don Preist of the TRE (Telecommunications Research Establishment), studying Nazi transmissions and collecting data in case Operation Biting didn’t come off.

An early snag was well and truly hit when the beach unit, commanded by Lt Euen Charteris, found themselves 2.5 km out from their destination.

They faced the prospect of running toward Bruneval. The route took them through a village brimming with Germans. Thankfully the night gave them the cover they needed, though one enemy soldier was dispatched after joining them in a jog… the unfortunate soul figured they were Nazis.

Meanwhile, Cox and company were at the radar disc. Hitler’s forces were prepared for the parachutists’ arrival and hot metal flew everywhere. It also became clear the kit couldn’t be pried away with tools. Brute strength was used to dismantle the parts. These were then put on trolleys, with accounts of the loot being ridden down slopes to the escape route.

Lt Charteris reached the coast and the mainly Scottish team engaged with the enemy in a fight to the finish. Boats were supposed to be waiting for them but these had been forced to hold off while German vessels prowled the waters. Eventually help arrived, and the Brigade were sped away to Portsmouth.

Sadly while casualties were low, 2 men died. One of those was Lt Charteris. The Germans lost 5 men. 6 of the group became prisoners of the Nazis. The Brits captured soldiers of their own and brought them back to extract further information.

The Parachute Regiment’s ParaData website calls Operation Biting “a small but exciting taste of success at a time when the war was going badly.” It was a victory for Churchill in the media and in the national consciousness. The deadly radar-grabbing mission put Paras on the map and ushered in a new age of technological warfare.

They got the job done. Bravo Zulu to them!

ReplyDeleteHey Old NFO;

DeleteYeah they did