I read this article and it was full of stuff that I didn't know about Armalite and that they seemed to have a "spate" of bad luck, it seems. They design something really neat like the quintessential "America's rifle" like the AR-15 and its derivatives, then crash and burn later. Yes I got this from "American Rifleman.

Bringing Small Arms Into The Space Age

As detailed in The ArmaLite AR-10 by Maj. Sam Pikula, USAR, The Black Rifle by R. Blake Stevens and Edward C. Ezell and the company’s own official history available at armalite.com,

the ArmaLite story starts with George Sullivan, patent counsel for

Lockheed Aircraft Corporation. Visionary, firearm enthusiast and

huckster all describe Sullivan. His job at Lockheed was crucial to

subsequent events because it meant that Sullivan was aware of the latest

technological breakthroughs and space-age materials at a time when the

American small-arms industry was stagnated and relatively antiquated.

Small arms were built only of steel and wood, and new products were

simply derived from evolutionary changes to old ones.

While not a professional, Sullivan had a passion for small-arms

design. Through contacts in the aviation industry, that passion

eventually came to the attention of fellow firearm enthusiast Richard

Boutelle, who happened to be president of Fairchild Aircraft. Boutelle

was intrigued by Sullivan’s ideas and, in the early 1950s, provided

funding for a foray into the business of designing small arms. Sullivan

set up shop in Hollywood, Calif., in a small building affectionately

referred to as “George’s Backyard Garage.” Initially, the hope was to

create sporting arms for the commercial market using modern, high-tech

materials. The first effort, for example, was a .308 Win.-cal.,

Mauser-style bolt-action with a foam-filled plastic stock and aluminum

receiver and barrel with a thin steel liner. Very few examples of this

rifle, variously called the AR-1 and “Parasniper,” were produced.

A 1950s AR-10 prototype (l.) is shown

next to a state-of-the-art AR-10A4 flat-top, this one mounted with an

Arma-ment Technology ELCAN 3.4x scope.

As envisioned by Sullivan, ArmaLite was not intended to be a

firearm manufacturer; ArmaLite’s stock-in-trade was to be ideas. The

company would use knowledge of materials and manufacturing techniques

gleaned from the aircraft industry to create radical new designs. It

would then build prototypes of those designs and market them to

manufacturers who would produce them under license. Sullivan proposed

that Fairchild purchase ArmaLite

and make it a division of the company, and in that way inject

additional capital into the venture. Boutelle agreed and, on October 1,

1954, ArmaLite became a division of Fairchild Aircraft.

A Change Of Direction

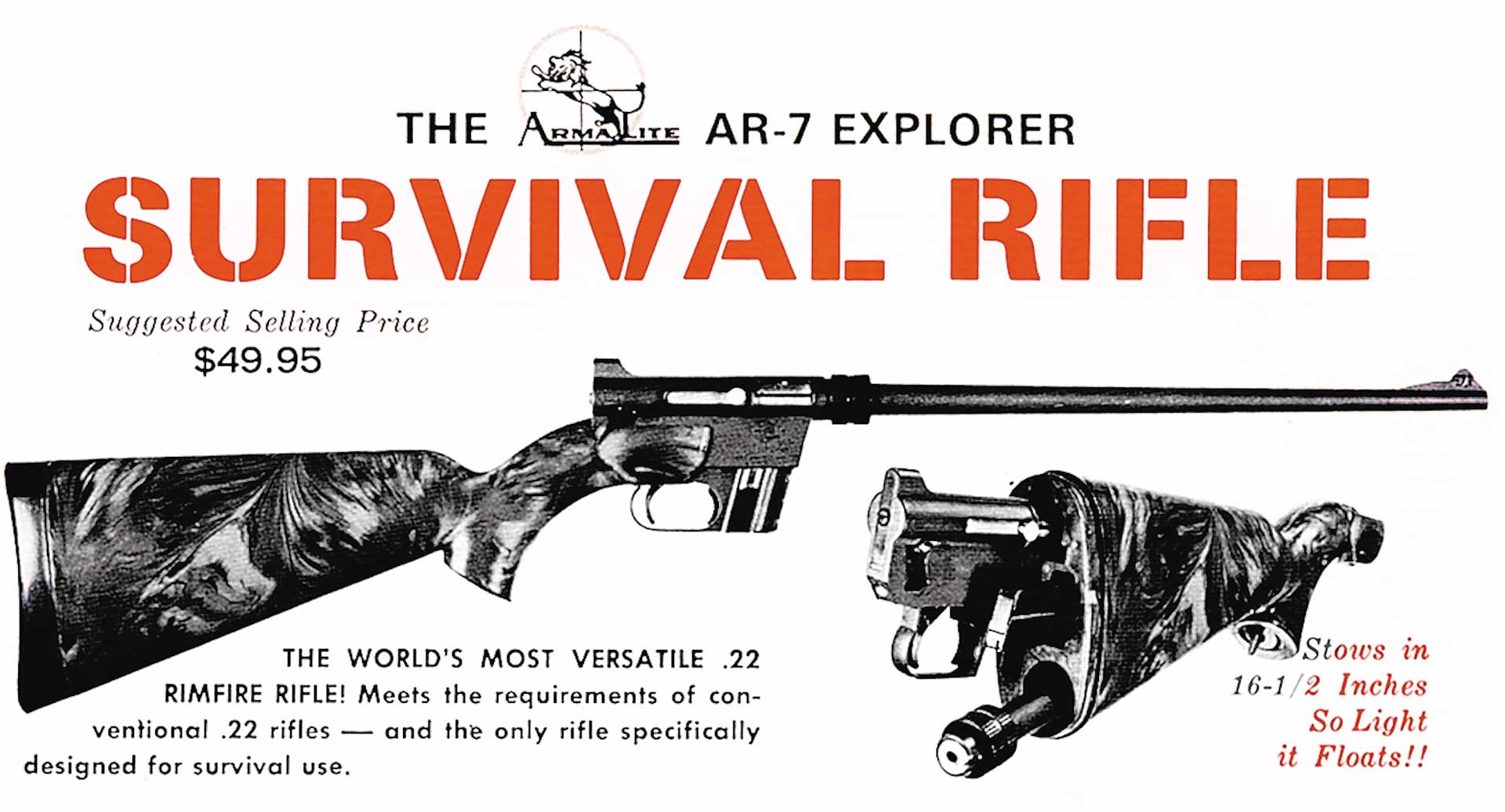

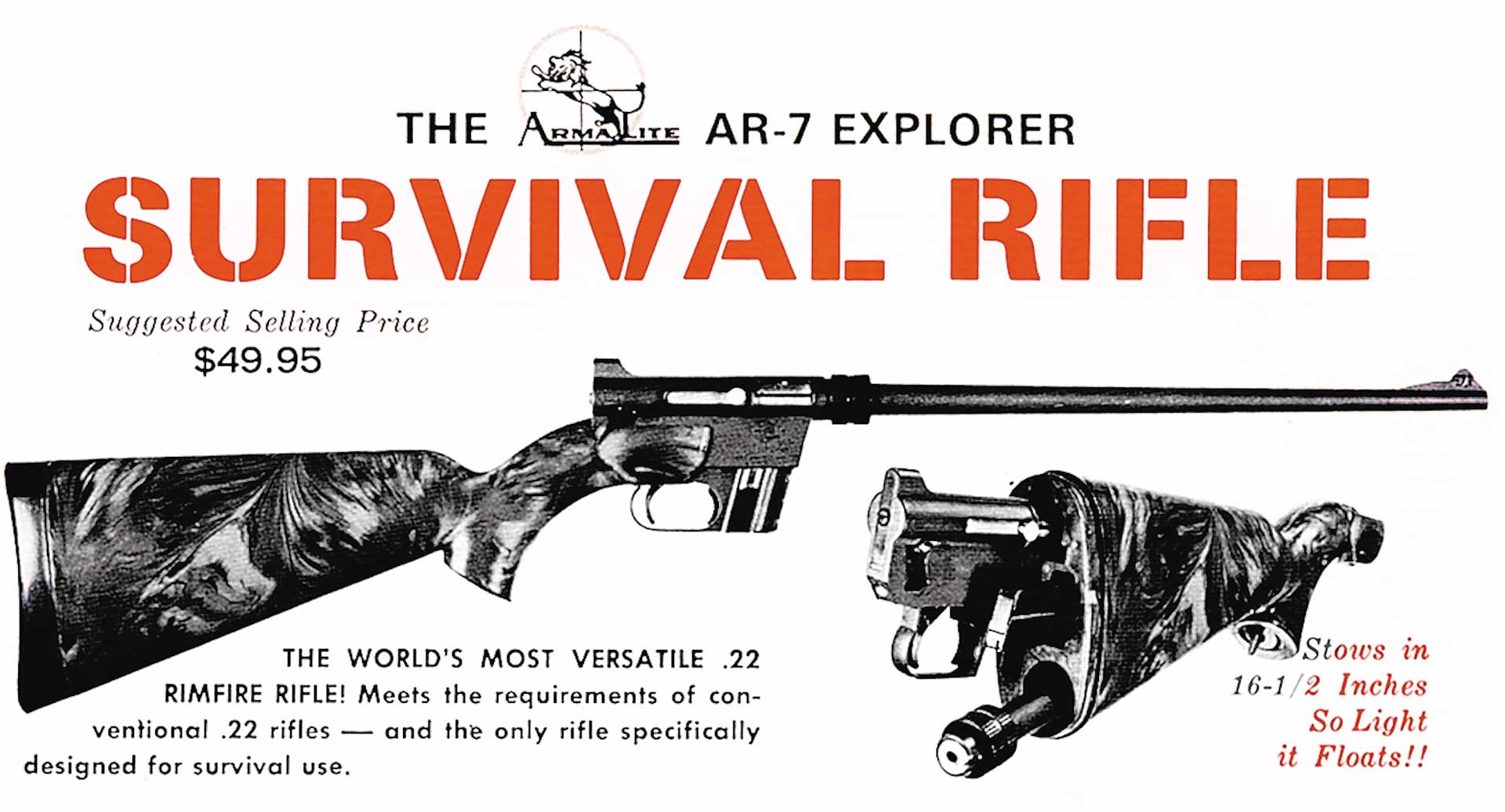

The AR-7 was a commercial, .22 LR-cal.

version of the Air Force AR-5 survival rifle. The barrel and action

could be detached and stored within the stock.

Shortly thereafter, ArmaLite was invited to submit a rifle for

consideration by the Air Force for its new survival rifle. The firearm

the company submitted, a .22 Hornet-cal. bolt-action takedown with a

four-shot magazine, was dubbed the AR-5. The gun’s barrel could be

detached from the action and stored in the plastic stock. With the

buttcap then replaced, the 2 3⁄4-lb. gun could float. The Air Force adopted the gun as the MA-1,

but never purchased it in quantity. Despite that, though, the interest

shown by the military took ArmaLite in a whole new direction. From that

moment on, the company would focus on military designs.

While testing an ArmaLite prototype at the Topanga Canyon Shooting

Range in southern California, Sullivan met a gentleman who lived in

nearby Los Angeles and made dental plates for a living. He was a former

Marine who also happened to be an amateur firearm designer. In fact, he

was testing one of his own designs that day. His name was Eugene Stoner.

Shortly thereafter, Stoner found himself in the employ of ArmaLite as

its chief design engineer.

While Sullivan had been the company’s visionary, day-to-day

operations were run by Charles Dorchester, who served in numerous

executive capacities, including president and eventually chairman of

ArmaLite. While the company conceived and developed various designs, it

was a semi-automatic rifle with an unusual locking action and unique gas

system that would make Stoner—and ArmaLite—famous. It was called the

AR-10 and was the focus of ArmaLite’s efforts from 1955 until 1959.

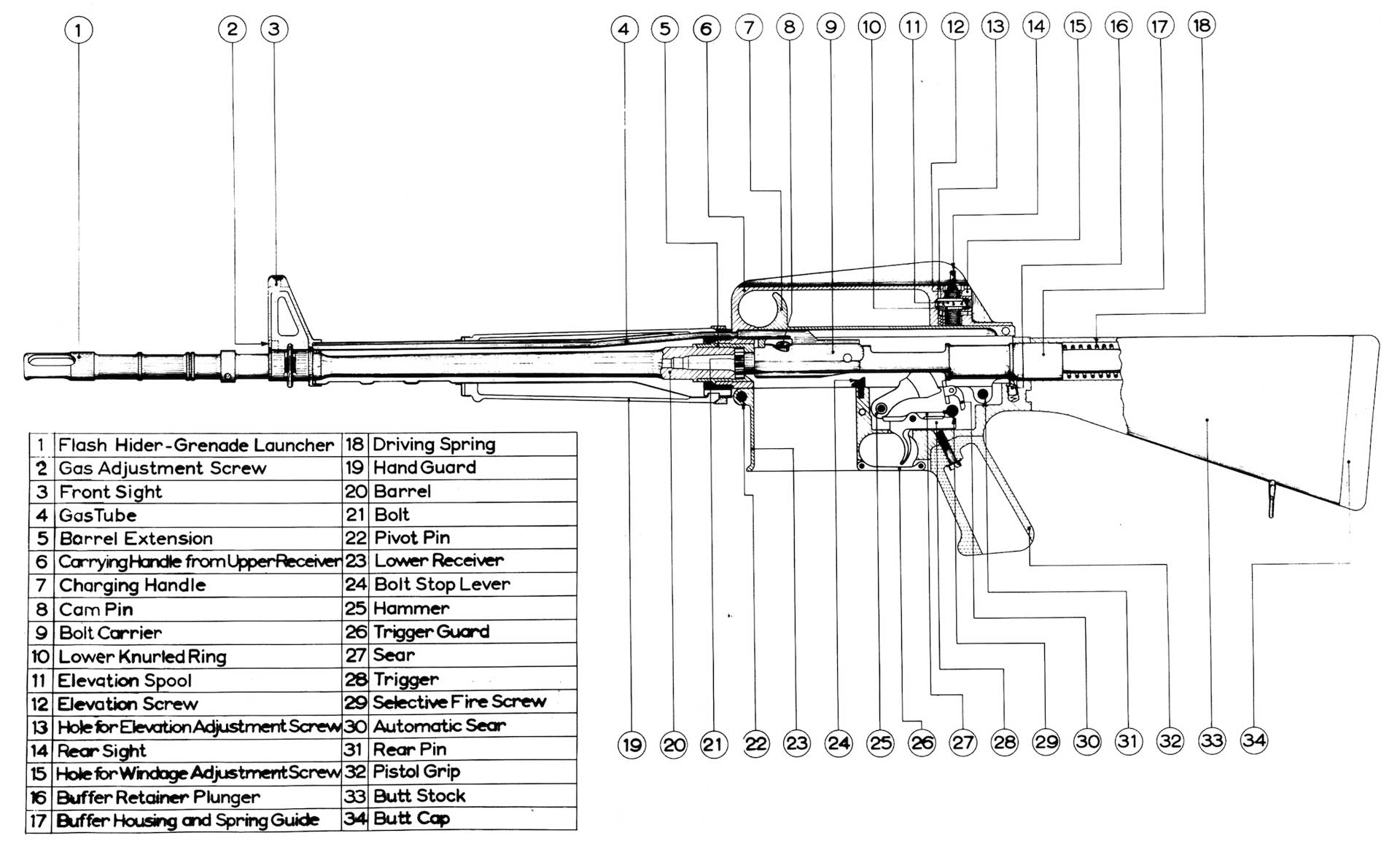

Tomorrow’s Rifle—Today

The AR-10 looked

radically different from anything previously seen. It had an integral

carry handle atop the receiver that contained the gun’s iron sights. The

cocking lever was on top of the receiver and articulated in the opening

of the handle. The fore-end was not wood, but fiberglass and, later,

plastic, thanks to plastics engineer Tom Tellefson. Inside, it was just

as radical with an eight-lug, rotary bolt locking not into the receiver,

but into a steel barrel extension. That allowed the receiver to be made

from lightweight, rustproof, forged aluminum rather than heavy,

rust-prone steel.

The rotary bolt and barrel extension was borrowed from the Johnson rifle designed by Melvin M. Johnson.

(Johnson was the East Coast military rifle consultant for ArmaLite and

had a contentious relationship with the military dating back to his

efforts to get the Johnson rifle adopted in place of the M1 Garand. Some

speculate that his involvement with ArmaLite didn’t help the company’s

chances with the military.) The lock-up may have been Johnson’s, but the

gas system was Stoner’s.

As described in The Black Rifle:

“[S]toner’s gas system

utilized a simple open pipe, a concept first used in the Swedish

Ljungman Gevar 42 and the later French 1944 and 1949 MAS semi-automatic

rifles. In these relatively rudimentary applications, the gas piston and

spring of a conventional gas-impingement system were replaced by the

jet of hot gas itself, which traveled back through the hollow gas tube

and impinged directly onto the face of the bolt carrier. The kernel of

genius in Stoner’s gas system was that the AR-10’s gas tube, running

along the left side of the barrel under the handguard, fed the gas

through aligned ports in the receiver and bolt carrier wall into a

chamber formed between the tail of the bolt and the surrounding bolt

carrier. This forced the bolt carrier back. After about 1/8” of

movement, the port in the carrier no longer lined up with the port in

the receiver, and the further flow of gas was cut off. The momentum

already imparted was sufficient to keep the bolt carrier moving, which

unlocked the bolt by rotating it with a connecting cam pin, thus

beginning its rearward travel. With the gas cylinder at maximum size and

the bullet long since out of the muzzle, what little pressure remained

was exhausted as a weak ‘puff’ through slots in the right side of the

bolt carrier.”

Battling The Big Boys

The gun was quickly entered into the

ongoing service rifle competition then pitting the Springfield T44

against the T48, a version of the FN FAL.

The AR-10 arrived on the scene too late and with too little development

to best the other rifles in the trials and the contract was awarded to

the T44, which was adopted by the military as the M14.

However, a handful of researchers at Aberdeen Ballistics Research Laboratories—among them American Rifleman

Ballistics Editor William C. Davis—had come up with some pretty radical

notions of their own. Despite years of insistence by Army brass on

.30-cal. rifles for combat use, some ballisticians within the military

had begun to explore the feasibility of lesser calibers. The Hall Study,

conducted by Donald L. Hall, had concluded that, given a rifle and

ammunition combination with a total weight of 15 lbs., a soldier armed

with a small-caliber rifle could kill, on average, 2.5 times as many of

the enemy as a soldier armed with an M1 rifle and ammunition.

This was followed shortly by The Hitchman Report prepared by Norman

Hitchman. It determined that most soldiers do not engage the enemy until

he has closed to 300 yds., and that hit potential was rather low until

combatants had closed to 100 yds. Therefore, the accuracy and power of

.30-cal. U.S. battle rifles—built to a 600-yd. standard—were excessive.

Practically speaking, equal results could, in theory, be achieved with

smaller, less powerful, less accurate and less costly arms. This led to

the Small Caliber, High Velocity (SCHV) concept. In addition to

maintaining practical effectiveness, a small cartridge would recoil

less, be more controllable in fully automatic fire (a distinct problem

encountered with the .308 Win.-cal. M14),

could be carried in greater quantity by individual soldiers and would

allow a lighter, handier rifle than a .30-cal. cartridge. ArmaLite was

consequently asked to explore reducing the AR-10 to .22-caliber. The

company agreed, though it continued to seek sales of its .30 cal.

domestically and abroad.

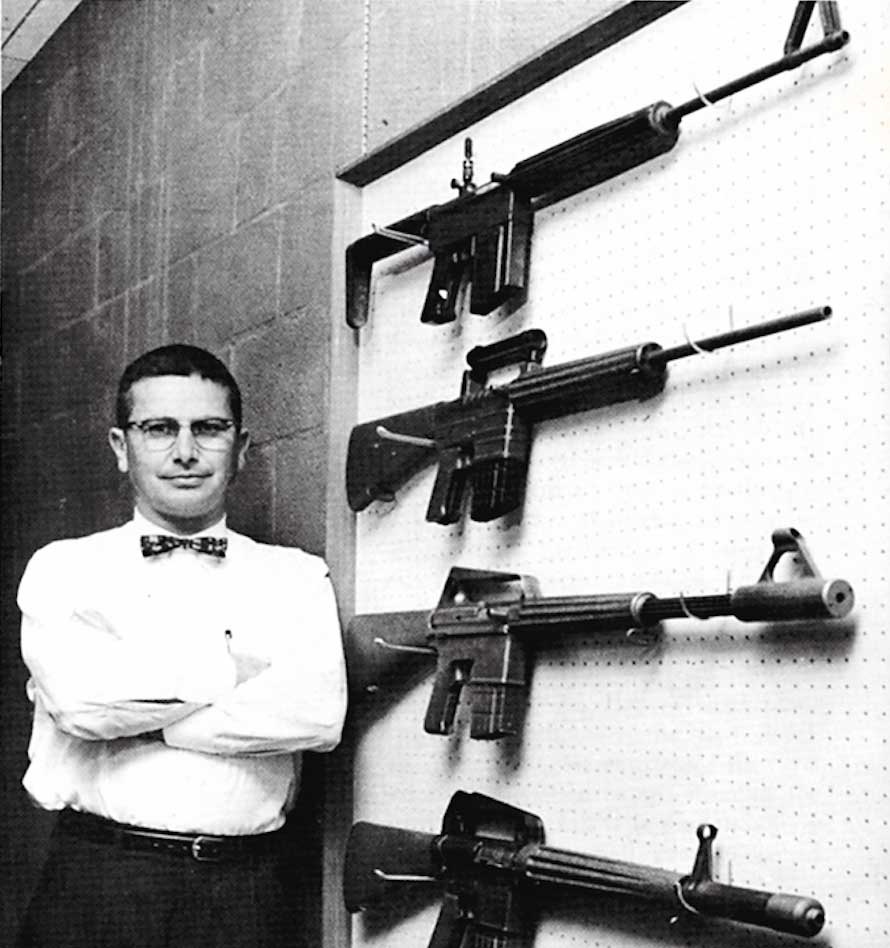

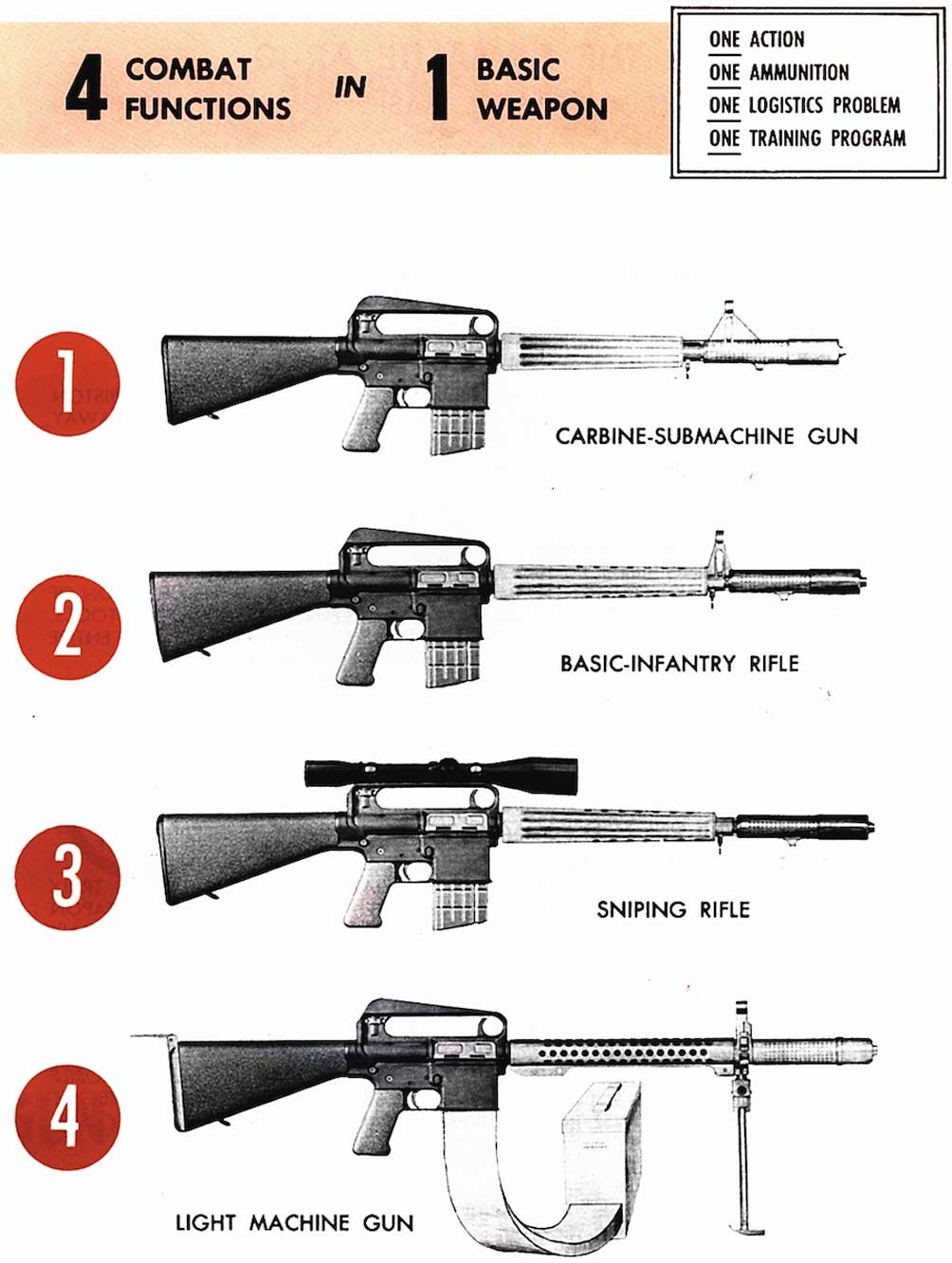

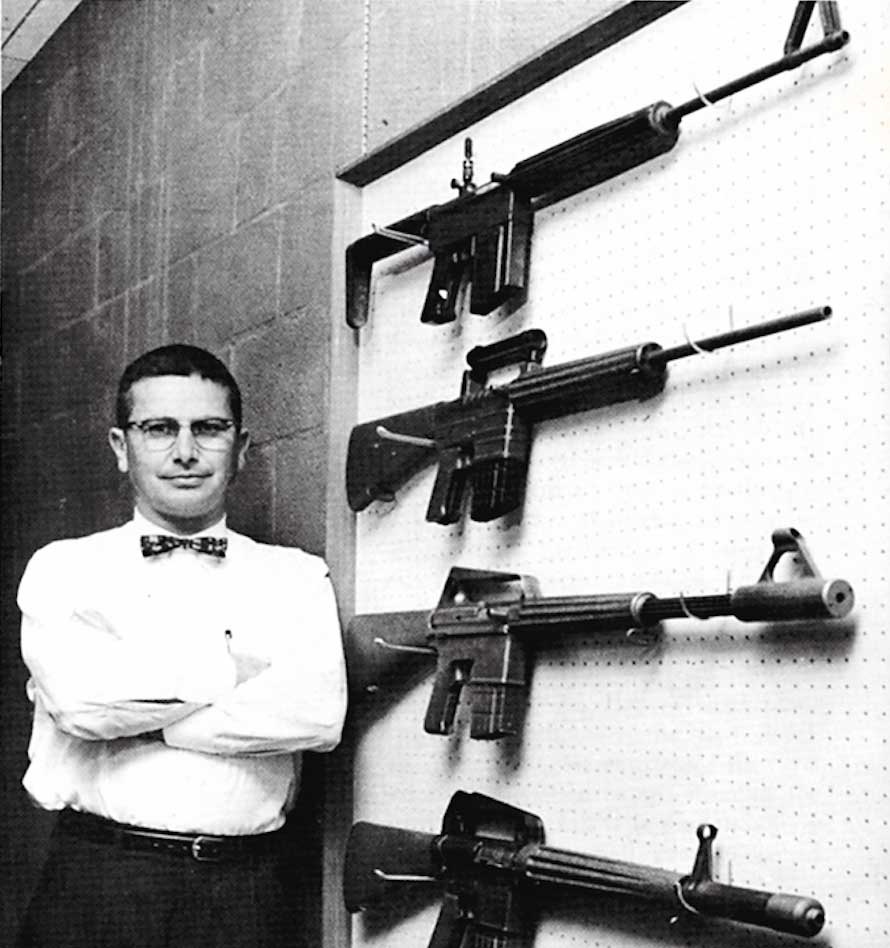

Firearm designer Eugene Stoner poses

beside various incarnations of the AR system. His greatest strength may

have been his ability to take clever, yet disparate design elements and

integrate them into a single, functional firearm. The AR-15/ M16 that

evolved from his design has been with us for about 40 years now.

When the military requested that ArmaLite investigate downsizing the

AR-10 to accommodate a .22-cal. cartridge, it’s doubtful the company

realized how significant the request was to prove. Modifying the .222

Rem. cartridge and freely building on the work done at Aberdeen,

Stoner—no ballistician—created the round that eventually became known as

the .223 Rem. (5.56 mm NATO). Meanwhile, Arma-Lite designers Robert

Fremont and L. James Sullivan downsized the AR-10, not an easy task

since it wasn’t a matter of a consistent ratio of reduction from the

large gun to the small one.

Once completed, the new gun—referred to as the AR-15—was largely

ignored by the military bureaucracy that had initiated its development.

Factions within the military were still uncomfortable with SCHV, while

some felt the military was too far along in its commitment to the new

M14 service rifle to change at that point.

From Bad To Worse

In the meantime, things

were going badly with the AR-10. It is important to remember that

Armalite was conceived of as a design shop rather than a manufacturing

entity. The company contracted with Artillerie-Inrichtingen, the Dutch

arsenal, to build the rifle, hoping for sales to foreign militaries.

However, the company had never had the funds to properly develop the gun

completely. There were numerous bugs that had to be worked out of the

design, bugs a larger company might have anticipated and dealt with

easily. Moreover, manufacturing obstacles continually delayed

production, frustrating ArmaLite executives. Further, with the exception

of a contract with Sudan—which no one has ever mistaken for a world

power—the rifles weren’t selling, even to the Dutch whose arsenal was

building them.

AR-180B (.223 Rem.)

Finally, with no future AR-10 sales on the horizon, the

military’s interest in the SCHV concept apparently waning and Fairchild

strapped for cash, ArmaLite chose to cut its losses and, in early 1959,

licensed the rights to both the AR-10 and AR-15 designs to Colt’s

Manufacturing for $75,000 and a 4.5 percent royalty.

Although it is widely regarded as a milestone in the history of bad

ideas, the licensing agreement with Colt’s was not irrational given what

was known at the time. Colt’s—itself near bankruptcy—was taking a

gamble. Fortunately, that company’s luck was much better than

ArmaLite’s. Its luck came in two forms: rising tensions in Vietnam, and

the person of Robert W. “Bobby” MacDonald.

New Shooter

When the U.S. decided to

intervene in Southeast Asia, it helped set the stage for the ultimate

triumph of the AR-15. The election of John F. Kennedy and the

appointment of Robert S. McNamara as Secretary of Defense meant that

change had come to arms procurement. With McNamara’s “Whiz Kids” steeped

in no tradition save arrogance, the traditional channels of trial,

development and adoption could be breached. That is just what happened

when Colt representatives took the AR-15 to Indochina.

The American government had decided that, despite the focus on

strategic nuclear weapons, small arms for fighting limited wars against

insurgents were needed and had been neglected. Developing and securing

such weapons was to be the mandate of the Advanced Research Projects

Agency (ARPA). These weapons were not to be carried by U.S. personnel,

per se, but were to arm U.S.-backed foreign nationals. It was the result

of such a program, specifically Project AGILE, that brought Colt’s

representatives, including MacDonald and now Stoner, to the Far East to

demonstrate the AR-10 and AR-15. The smaller arm was a tremendous hit

with the diminutive foreign troops. The gun and its shooting

characteristics appealed to those of smaller stature far more than did

the AR-10 or any other .30-cal. battle rifle. Moreover, the AR-15 had

virtually no competition from like-chambered combat rifles—there were

none. MacDonald promptly informed Colt’s to focus on the AR-15 rather than the AR-10 and to gear up for the Asian market.

ArmaLite AR-10A4 (.308 Win.)

Stateside, MacDonald was no less effective. At Boutelle’s

birthday party in Maryland, MacDonald handed Air Force General Curtis

LeMay an AR-15 and let him shoot a couple of watermelons with

devastating effect. The result was two exploded melons and LeMay’s quick

request that AR-15s be purchased to replace M1 Carbines for Air Force personnel responsible for the security of Strategic Air Command bases.

In Vietnam, the role of the “black gun” continued to expand. Although

it was supposed to be issued only to foreign troops, U.S. personnel

gradually began carrying the new rifle, too. Obviously, this made

logistic sense since they were traveling with AR-15-equipped ARVN

soldiers. But also, American personnel noted that the light,

fast-handling gun was better suited to jungle warfare than any other

battle rifle-caliber longarm available. At first it was issued only to

specialized personnel, but soon became a general-issue arm. ArmaLite

could only watch in bitter astonishment as the AR-15 became the

standard-issue U.S. service rifle, supplanting the bulky M14.

There were, of course, problems with the AR-15 (which was

subsequently given the military designation M16). Many of those problems

were directly attributable to how the arm was adopted—without adequate

testing of the gun nor training for the soldiers. However, with the

wherewithal that comes from having enormous government contracts,

Colt’s, with Stoner as a consultant, was eventually able correct serious

problems, especially the extraction and jamming issues that plagued the

early guns and were only discovered after the rifles were widely

issued.

After having reduced the AR-10 to produce the AR-15, ArmaLite

reversed course and took what had been learned from the AR-15 and scaled

it up to create a new, improved AR-10 called the AR-10A.

The future, however, was clearly with the .223-Rem.-chambered rifle,

and it appeared that the age of the AR-10 would never come.

ArmaLite M15A2 National Match (.223 Rem.)

The Dream Winds Down

Boutelle was

eventually relieved of his position with Fairchild. George Sullivan, the

ArmaLite muse, landed more softly: He had never left his position with

Lockheed.

Recognizing that the .223 Rem. was the hot ticket, ArmaLite was faced with the problem that the AR-15 patents now belonged to Colt’s.

The company then created a “poor man’s .223” called the AR-18. It was

to be a low-cost .223 rifle made from stampings rather than forgings and

having a different gas system than the AR-15. It would allow

less-wealthy countries to equip their militaries with a .223 Rem.-cal.

rifle.

However, despite two decades of effort, the company’s luck ran true

to form and sales of the AR-18 were very limited. In the end, ArmaLite

was sold to Elisco Tool Manufacturing Company, a Philippine concern

whose U.S. component folded with the overthrow of Philippine president

Ferdinand Marcos.

Restoring The Dream

In January of 1994,

Mark Westrom, a former Army Ordnance officer and civilian employee of

the Weapons Systems Management Directorate of the Army’s Armament

Materiel and Chemical Command (AMCCOM) purchased Eagle Arms, a small

company that made AR-15-type rifles and parts following the expiration

of Stoner’s patents. A business associate of Eagle Arms, Dr. John

Williams, had worked for ArmaLite in his youth and introduced Westrom to

former ArmaLite Production Manager John McGerty who, in turn,

introduced Westrom to John Ugarte. Ugarte had been the last president of

record at ArmaLite and had retained the rights to the trademark;

Westrom promptly purchased those rights. Thus was the ArmaLite marque

reborn.

Japan

Air Self-Defense Force Honor Guard members participate in a drill

performance during the 2017 Friendship Festival, Sept. 17, 2017, at

Yokota Air Base, Japan. (U.S. Air Force photo / Airman 1st Class Juan

Torres - 170917-F-KG439-0111).

Japan

Air Self-Defense Force Honor Guard members participate in a drill

performance during the 2017 Friendship Festival, Sept. 17, 2017, at

Yokota Air Base, Japan. (U.S. Air Force photo / Airman 1st Class Juan

Torres - 170917-F-KG439-0111). Members

of the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force Special Honor Guard stand in

formation at the Ministry of Defense in Tokyo on Nov. 7, 2016. The JGSDF

held a welcoming ceremony for U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David

L. Goldfein as part of his first visit to the region as Air Force chief

of staff. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Michael Smith).

Members

of the Japanese Ground Self-Defense Force Special Honor Guard stand in

formation at the Ministry of Defense in Tokyo on Nov. 7, 2016. The JGSDF

held a welcoming ceremony for U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David

L. Goldfein as part of his first visit to the region as Air Force chief

of staff. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Michael Smith). Right side view of Beretta BM59E rifle SN #5347812 (formerly Springfield M1 rifle SN #5347812).

Right side view of Beretta BM59E rifle SN #5347812 (formerly Springfield M1 rifle SN #5347812).

A

U.S. Army Soldier displays an M1 rifle discovered in a suspected

insurgent's home in Western Muqdadiyah, Iraq, Dec. 12, 2007. The Soldier

is from Alpha Company, 2nd Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, 3rd

Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division. (U.S. Army photo by SPC

Shawn M. Cassatt).

A

U.S. Army Soldier displays an M1 rifle discovered in a suspected

insurgent's home in Western Muqdadiyah, Iraq, Dec. 12, 2007. The Soldier

is from Alpha Company, 2nd Battalion, 23rd Infantry Regiment, 3rd

Brigade Combat Team, 2nd Infantry Division. (U.S. Army photo by SPC

Shawn M. Cassatt).