Owning an M1 Carbine is on my bucket list for owning a rifle, but the cost of a specimen is easily $1200 bucks for a decent unmolested version. I missed the boat I guess on owning one, unless I win the lottery, LOL

I ran across this article from the "Sandboxx", and it had rifles that I never heard of, and I thought it was a really cool"Snapshot of Time".

The M1 Carbine is a legendary weapon that served our Soldiers, Marines, and Sailors well throughout numerous conflicts, earning its place in the hearts of many vets and historians alike. This handy little rifle came out of the Light Rifle Program that began after Uncle Sam found the M1 Garand was too much gun for a lot of troops. As a big, full-powered battle rifle, it worked well for infantry but was cumbersome for truck drivers, artillerymen, radiomen, and others. Thus, the desire for a light rifle reared its head.

In 1940, the United States launched the Light Rifle trials, seeking a new weapon that was neither traditional battle rifle nor submachine gun. The Army demanded a platform that offered more range, accuracy, and firepower than a handgun while weighing half as much as the M1 rifle and famed Thompson SMG. In order to make those demands a reality, the effort also led to the development of the 30 Carbine round by Winchester. There were several rifles submitted, and oddly enough, the M1 Carbine wasn’t even a part of the program’s initial trials.

We’ve talked about the M1 Carbine at length before, and you can read all about it in our full feature here. So now, let’s look at the light rifles that could have been if the M1 hadn’t won the day.

Related: Why the M1 Carbine became an American legend

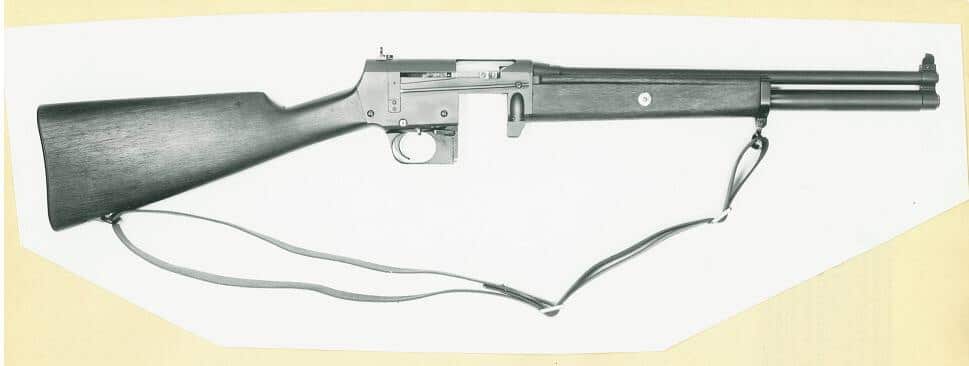

Auto-Ordnance Carbine

Two Auto-Ordnance carbines were made for the light rifle trials. Both used the same core design, but the second rifle had a number of improvements added after the initial trials. These weapons utilized a short recoil system that’s rather interesting and require a slight rearward movement of the barrel to function.

Auto-Ordnance designed five-round and thirty-round removable magazines for the weapon. The barrel was a short 15.6 inches, and the overall length was only 35 inches.

The first tests destroyed the rifle, and Auto-Ordnance rebuilt the gun into the second model. The second model featured selective fire, an optional compensated barrel, and a magazine that would auto eject when the weapon fired the last round.

The Auto-Ordnance carbine was deemed too complicated for service, with too many small parts and too many major reliability issues that couldn’t be resolved.

Thompson Carbine

Another model submitted by Auto-Ordnance was a model of the Thompson chambered in 30 Carbine. This delayed blowback weapon offered selective-fire capability and was fed from 20 or 30 round magazines.

The only major differences between the carbine and famed Thompson Submachine Gun were a quick change barrel, reduced weight, and an in-line stock.

This weapon performed well and even outperformed the M1 Carbine in accuracy and reliability.

However, this light rifle wasn’t so light. In fact, it was rather hefty and didn’t meet the weight standards set by the U.S. Army. Plus, like the Thompson SMG, the price was high for production. Thus, the weapon didn’t become America’s light rifle.

The Garand Carbine

John Garand, of M1 Garand fame, also designed his own light rifle. This gas-operated gun was remarkably light at 4.91 pounds and utilized an 18-inch barrel. The overall length was 34.9 inches, and the weapon used 5, 20, or 50 round detachable magazines.

Those magazines are mounted to the top of the rifle at an offset 45-degree angle, which forced the iron sights to be offset, and the charging handle was positioned across the top.

The only benefit this design could offer would be the ability to obtain a much lower profile when firing from the prone position.

The weapon performed admirably, but the tester didn’t like the magazine placement. Garand and Springfield revamped the weapon into a more conventional layout, but the weapon was found to be insufficient at the end of testing.

Hyde-Bendix

George Hyde designed the Hyde-Bendix rifle. His little carbine was gas-operated and weighed 5.3 pounds and 33.6 inches long overall. The rifle performed well and was decently accurate. However, the weapon had a few flaws, including the need for a stronger operating spring. It was thought to be simple, however, and functioned well in austere environments.

Hyde took the weapon back to the factory and made some changes. This included ditching the pistol grip and swapping out some internal components… but the newer model proved inferior in function in just about every way. Heck, it was even heavier. Thus, the Hyde-Bendix rifle languished.

Related: These are the longest-serving weapons in the US arsenal

H&R Light Rifle

The H&R Light Rifle came from the mind of Eugene Reising. Reising had great ideas, but often, they were ideas the world simply wasn’t ready for. He designed the M50 submachine gun, and his Light Rifle was just the M50 turned into a 30 carbine. The M50 Reising, however, kind of sucked, and so did the H&R Light Rifle. The first gun used a delayed blowback system taken directly from the old M50.

H&R’s Light Rifle proved to be accurate and simplistic, but suffered from bad magazines, ruptured cases, and other issues. H&R redesigned the weapon to be gas-operated, which helped solve some problems. However, it never became as reliable as the army needed it to be.

The Savage Carbine

In the 1940s, Savage did well in the arms industry, and the Savage carbine got sent to the Light Rifle trials. This short recoil-operated rifle is mixed with a rotating bolt to provide a novel operating system. It weighed just 5.45 pounds and utilized a 16-inch barrel with an overall length of 33 ⅜ inches. Magazine capacities ranged from 5 to 20 rounds in box magazines and 50 round in drums.

The Savage carbine didn’t last long. After 2,882 rounds, the rifle cracked at the breech. Savage did not receive a second solicitation as the Army found their carbine too complex with too many small parts.

Turner Carbine

Most of these guns resemble a standard wood stock rifle, maybe a Thomspon, but the Turner was something else entirely. It looked more like the inexpensive British Sten gun than any of its competitors. The Turner Carbine lacked any wooden furniture and wore a perforated metal handguard and wooden wire stock with a leather butt pad, which would have made it light and inexpensive to produce.

It turned out big army wasn’t ready for it and requested a more traditional rifle with a wooden stock. Turner obliged and sent a second model.

Body guns used a long-stroke gas piston system that acts on a titling bolt that locks to the side of the receiver. The back of the weapon featured an Allen screw that allowed the selection of semi and full-auto modes.

The first variant was thought to be average and rather reliable. However, the all-metal stock and perforated handguard didn’t inspire great ergonomics. The second variant proved to be extremely unreliable and of much lower quality, earning it the ax as well.

Woodhull Carbine

Cute describes the Woodhull light rifle well. In a lot of ways, it looks like a shrunk-down Browning Automatic Rifle. The big wooden handguard, the square receiver, and wood stock have that BAR look. In reality, the Woodhull, made by Frank Woodhull, copied the Winchester Model 1905. His rifle was 29.8 inches long with a 17.3-inch long barrel, and the weapon weighed 5.5 pounds.

The Woodhull used a crude and simplistic direct blowback design that relied purely on the weight of its heavy bolt to keep the breech closed until the weapon could safely cycle. The requirement for selective fire had Woodhull install a slot that needed a key to switch from safe to full auto.

The Woodhull carbine never performed reliably. Even a second variant was submitted, and still, the rifle remained unreliable.

The Light Rifle

The Light Rifle trials ended without a winner. However, the information from the trials would later have the Army and Winchester work together to develop what we now know as the M1 Carbine. Winchester’s rifle was placed against the other competitors and performed well. Some outperformed the M1, but they were usually too complicated or too expensive.

The M1 Carbine, on the other hand, checked all the boxes for Army use and would go on to become an absolute legend. And like most legendary weapons, it sent a fair number of challengers to scrap heap along the way

Yeah, there are STILL people who say the fix was in from day one. But nobody knows and the ones that did are long gone.

ReplyDeleteI can and do kick myself constantly for not getting one or three when they were cheap and available, along with a Garand or two, a couple M1903s and some M1917s (once I found out about them.)

ReplyDeleteStupid me...