I ran across this article reading my American Rifleman magazine, and I found it fascinating. it is on my bucket list to visit this and the Imperial War Museum once all this Covid restrictions and other stupidity is relaxed. I also want to check out the "HMS Belfast, she is a museum ship in the Thames River. We will see though.

It was London, it was September, it was raining.

Outside the Brigade of Guards Museum, near Buckingham Palace, the statue of Field Marshal Earl Alexander of Tunis stands 15' high—a tribute to Britain’s greatest field commander of the 20th century. His trademark sheepskin is faithfully reproduced in a half-ton of bronze, and even here he manages to wear it like a dinner jacket. England’s greatest combat soldier was also known as the best-dressed man in the regiment.

As the rain pelted harder, plastering the brown beech leaves to the paving stones and forming tiny waterfalls in the creases of the jacket, Alexander—or “Alex,” as he was known to all—took no notice. He kept his eye fixed firmly on the entrance to the museum, and suddenly that seemed like a heck of a good idea as the sky opened up and the cold rain came down in sheets.

The Guards regiments are among Britain’s most famous icons. They are the soldiers in red tunics and black bearskins who mount the guard on Buckingham Palace, among other places. What is less well-known is that they are also elite soldiers who have fought the king’s wars around the world for centuries. The oldest regiment is the Scots Guards, followed by the Grenadiers and the Coldstreams. The Irish Guards—Alexander’s regiment—and the Welsh are the youngest.

Inside the museum, one tableau after another depicts their exploits at Waterloo, Dunkirk, South Africa, Flanders. The displays, colorful at first, turn slowly sodden and muddy as all the gentility was wrung out of warfare, and red tunics were replaced by khaki (in South Africa) and brown service dress in the mud of Flanders. The display from the First World War includes bits of webbing, barbed wire, grenades, a bayonet. The stuff looks muddy even when it isn’t.

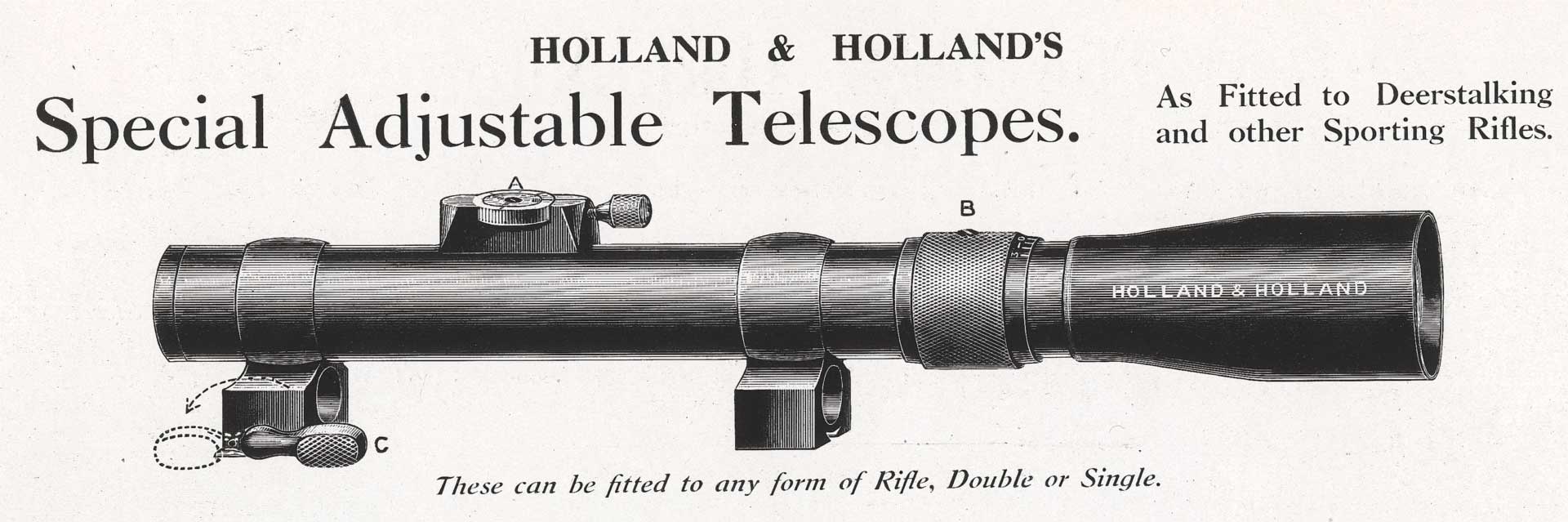

There is also a rifle. Not a Lee-Enfield, No. 1 Mk III, as might be expected, but a classic single-shot, break-action rifle of the type favored, before the war, for stalking stag in Scotland. It is of obviously fine pedigree, but has seen much hard use. The bluing is worn to a silver sheen and the stock is scratched and battered.

If you crouch down and peer closely, with the light exactly right, you can still read on the receiver “Holland & Holland.” It is an aristocrat among firearms, a “gentleman’s rifle”—a Royal Grade single-shot stocked in English walnut and finely checkered. At one time, the receiver displayed graceful engraving, although it is now worn almost completely away. Four years of trench warfare will do that.

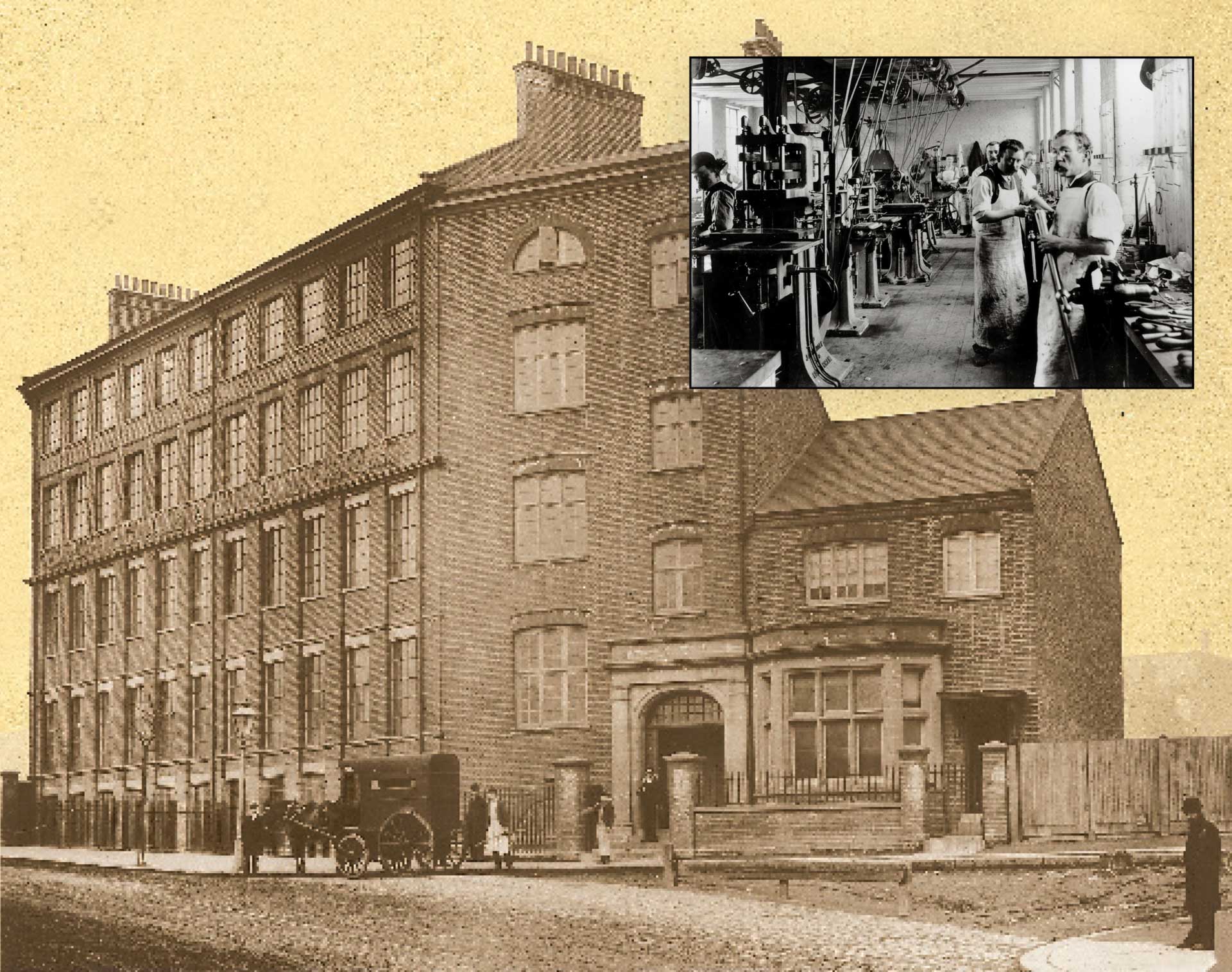

The story of how H&H rifle No. 26069 journeyed from the Bruton Street showroom to the Guards Museum is really one of convergence of the great names in pre-war England, in the military, in literature and in gunmaking. It involves Harold Alexander, Britain’s greatest soldier of the 20th century, and Field Marshall Lord Roberts, one of its greatest of the 19th; it involves Rudyard Kipling, Poet Laureate of the Empire and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature; and of course Holland & Holland, England’s greatest riflemaker.

The story begins with Lord Roberts in South Africa, fighting the Afrikaners in Britain’s first, and one of its bloodiest, military campaigns of the 20th century. There, Roberts renewed his acquaintance with Rudyard Kipling, an old friend from India.

Roberts was an Ulsterman, a gentleman of Anglo-Irish descent. For reasons no one has adequately explained, Ulster (Northern Ireland) has produced a disproportionate number of great British generals. The Duke of Wellington was an Ulsterman, as was Montgomery, among many others. In the South African campaign, the army’s Irish regiments performed spectacularly. To recognize their contribution, Queen Victoria ordered—on Roberts’ advice—the formation of a regiment of Irish Guards to join the Scots, Grenadiers and Coldstreams.

When he heard the news, Harold Alexander (also from Ulster) was 9 years old. He immediately decided that his future would lie with the Irish Guards. The son of the Earl of Caledon, he attended school at Harrow, went on to the military academy at Sandhurst, and joined his new regiment in London in 1911. He was a 22-year-old first lieutenant when the war broke out in 1914.

One of his fellow officers was the Earl of Kingston, and they shipped off to France together. In the Earl’s kit was the H&H rifle. It came to be there in a rather convoluted way.

As war in Europe approached, many Germans made last-minute visits to London to order rifles from the English gunmakers. One ordered a stalking rifle, and even provided a fine Voigtlander scope to be mounted on it. Ordered in 1913, it was barely finished when the Germans marched into Belgium. H&H could not ship a rifle to an enemy country, so the firm re-barreled the rifle to .303 British and fitted it out as a sniper rifle. A member of Parliament, Colonel Hall Walker, bought it and passed it on to Lieutenant the Earl of Kingston of the Irish Guards.

Recruit No. 26069 was in the quartermaster’s stores when the regiment went into action for the first time and was still there, amid the chaos of retreat, advance and retreat, before the war settled down to the hell of the trenches. By that time, the Earl of Kingston had been wounded and invalided back to England. Alexander fought with the regiment through the Retreat to Mons, was wounded in the First Battle of Ypres and returned home to convalesce. What happened then can be pieced together from scraps of information that have survived.

From the hospital, Kingston wrote to the commander of the battalion, Jack Trefusis, inquiring about his rifle. On January 6, 1915, Trefusis replied:

“My dear K.

It has been in QM Stores for ever so long and I have only just this moment heard of it. It was a thing we have wanted badly for a long time, and if we had only known of it in the last trenches we were in I have no doubt we should have accounted for a platoon of Germans. However we go back into the trenches on Friday and the rifle will be put into the most skillful hands I can find and a careful account of the bag that is made with it which I will report to you occasionally ... .”

The war was then barely four months old and Trefusis’s last paragraph is chilling:

“There is no officer here who was here with you except myself and Antrobus, and very few men. Poor Eric Gough was the last and he was killed last week.

“P.S.: I see I have never actually thanked you for letting us have the rifle, but I do enormously, it will put us on a more equal footing with those damned snipers, who are just as bad here as ever they were.”

As a military art form, sniping goes back several centuries, but it really flowered during the American Civil War. Not by coincidence, this was the first large-scale conflict in which trenches were used; trenches and snipers go together like coffee and cream. In the case of the British Army, through the late 19th century it fought mostly wars of movement until encountering the Boers in South Africa in 1899. Sniping was not a major factor, and while the British Army underwent a drastic reformation as a result, and became the best army of its size in the world, it still paid scant attention to sniping as it went to war in 1914.

Not so the Germans. When the German Army invaded Belgium, it had an estimated 20,000 sniping units ready to go. The Mauser Model 98 made an ideal sniper rifle; as well, when hostilities began the Germans collected thousands more accurate sporting rifles and sent them to the front. The British had but a handful of trained snipers, and few rifles with which to snipe. The German Army very quickly dominated “No Man’s Land” and the forward British trench lines. Trefusis’s rueful letter to the Earl of Kingston gives an idea of the havoc wrought by the German snipers.

When H&H rifle No. 26069 went into service with the Irish Guards and began to take its toll on the Germans, the call went out for more of the same. The War Office in London turned to H&H and the other fine rifle makers with orders for sniper rifles.

At the time, British gunmakers made three types of rifle: doubles, single-shots and bolt-actions. The doubles were mostly big-game rifles for Africa and India; bolt-actions went to the colonies, while single-shots—both break-action and falling block—were the classic stalking rifles for stag in the Scottish Highlands. As such, they were built to be accurate. Since the supply of Oberndorf Mauser actions had dried up for the British, they naturally built their sniping rifles to patterns like No. 26069.

A major problem was the supply of telescopic sights, and here the Germans, with their advanced optics industry, had a huge advantage. The War Office went so far as to try to smuggle scopes out of Germany by various underhanded means, but without notable success. This remained a problem until 1916, when British companies, like Aldis (of rangefinder fame), became capable of supplying telescopic sights in reasonable quantities. Until then, the gunmakers made do with whatever they had in inventory or obtained from civilian sportsmen.

The work went slowly at first, and by July 1915, H&H had fitted out only 10 more sniper rifles. Gradually, however, the pace picked up.

Another problem facing troops on the Western Front was the fact that German snipers concealed themselves behind pieces of armor plate. Early in the war there was little in the way of armor-piercing ammunition for standard rifles, and, again, the War Office turned to the London gunmakers. Figuring that any gun that could handle a Cape buffalo would punch through armor plate, Holland’s and the others shipped over 2,000 so-called “elephant guns.” These were a mixed blessing. While they demolished the armor well enough, the loud report combined with the smoke and belching flame revealed the shooter’s position to the enemy and brought down a rain of return fire.

Meanwhile, as H&H et al worked behind the scenes, rifle No. 26069 slogged on, killing Germans. Two weeks after his first letter to the Earl of Kingston, Jack Trefusis wrote again:

“The rifle has been an immense success and every Commander from C-in-C downwards has sent down to ask me about it, with the result that two are to be issued to each battalion.

“The sergeant major uses it and the score of Germans is for certain four killed and eight wounded in three days use ... . Those who were killed or wounded were fired at from a range of 800 yards. So it has been a great success.”

In March 1915, recovered from his wound, Lt. Alexander was promoted to captain, helped to form a second battalion of Irish Guards and returned to France commanding its No. 1 company. One of his officers was a subaltern named John Kipling.

Lt. Kipling was Rudyard’s son. Denied a commission because of his poor eyesight, the novelist appealed to his old friend Lord Roberts, who was now Colonel of the Regiment of the Irish Guards. Roberts’ influence was still immense, and he obtained a commission for the boy. Within a month, the battalion went into action at the Battle of Loos, where 800,000 men were ordered to breach a German position after a four-day bombardment by 1,000 guns. Five days and 45,000 casualties later, the attack was called off.

The unit that penetrated deepest into German territory was No. 1 Company of the 2nd Irish Guards under Captain Harold Alexander. When they withdrew, they left the body of Lt. John Kipling, shot through the head. He was one of 10,000 British soldiers whose bodies were never recovered from the all-swallowing mud of that battlefield.

In deep sorrow, and as a memorial for his son, Rudyard Kipling, Britain’s foremost author, agreed to write the official history of the regiment, The Irish Guards in the Great War, and the “telescope rifle” found its way into literature:

“Casualties from small-arm fire had been increasing owing to the sodden state of the parapets; but the Battalion retaliated a little from one ‘telescopic-sighted rifle’ sent up by Lieutenant the Earl of Kingston, with which Drill-Sergeant Bracken ‘certainly’ accounted for three killed and four wounded of the enemy. The Diary, mercifully blind to the dreadful years to come, thinks, ‘There should be many of these rifles used as long as the army is sitting in the trenches.’ Many of them were so used: this, the father of them all, now hangs in the Regimental Mess.”

Alexander and the Irish Guards also saw action at the Somme and Passchendaele, Cambrai, the retreat from Arras and, finally, Hazebrouk. In this battle, Alexander commanded the second battalion and helped save the channel ports from German attack, but the battalion was annihilated as a fighting force.

Rifle No. 26069 soldiered on with the 1st Battalion, accounting for who knows how many German soldiers. It helped win the sniping war, and the men of the Irish Guards came to love the trim little “gentleman’s rifle” because it saved so many of their lives. In 1918, it was retired from active service and given a place of honor in the regimental officers’ mess before being turned over to the Guards Museum.

There, it became part of a permanent display depicting the valor and the unspeakable horror of the war on the Western Front. And there it was, that rainy morning in September, when I took refuge from the London weather by ducking into the museum. When I emerged after a couple of hours, the weather had cleared and it was breezy and cool. Alexander’s statue, so stern in the rain, now appeared to be smiling in the sunshine.

During the Second World War, when he rose to the rank of field marshall and commanded the Allied advance up through Italy, Alex was always cheerful, always a gentleman, no matter how bad things became. When you have men like George Patton under your command, I expect good humor is invaluable. The plaque on the statue describes him as Britain’s finest battle commander of that war. Montgomery would have disagreed, but Alexander would have smiled and shrugged. His tombstone reads merely “Alex”; longer names are for lesser men.

I strolled along Bird Cage Walk, through St. James’s Park and up toward Mayfair. It is a pleasant walk up to Berkeley Square and 31-33 Bruton Street, home of Holland & Holland. The former director of the firm, David Winks, was waiting for me on an upper floor where the company’s own collection of classic guns resides.

Winks was in charge when the curator of the Guards Museum approached H&H in 1992 and asked them if they would take rifle No. 26069, much battered by the war and deteriorated after 75 years of benign neglect, and return it to its former glory.

David Winks agreed to clean it up but flatly refused to return it to pristine condition, although it could easily have been done.

“Those are honorable scars, honorably earned,” Winks told me.

“It would have been wrong to touch it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

I had to change the comment format on this blog due to spammers, I will open it back up again in a bit.