I saw this purely be accident whyle taking a break at work, so I being the caring individual, shamelessly "clipped" it for my Blog. I still am working all the crazy hours and will be until Labor day or a bit afterwards.

The US Navy at the end of WWII was the largest on the planet, and would be unaffordable at that size in peacetime. What followed was the largest warship preservation effort in history.

(WWII Cruisers USS Huntington (CL-107), USS Dayton (CL-105), and battleship USS South Dakota (BB-57) in mothballs at Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility Philadelphia, PA in August 1961. These warships had been in reserve for 14 years and show the characteristic “igloos”.) (official US Navy photo)

(The Suisun Bay, CA facility packed full of mothballed warships after WWII.)

The plan

In September 1945, immediately following the end of WWII, the US Navy put forth it’s first draft of what the peacetime fleet would look like. Using a very broad brush and not differentiating between types and classes, it recommended retaining 30% of it’s ships on active duty, placing 50% into mothballs, and scrapping 20%. Senator David Walsh (D-MA), an expert on naval affairs, calculated in September 1945 that this would require total manning of 500,000 men.

The post-WWII mothballing effort was a juggling act between the need to get men back to civilian life, and the need for their services to lay up the fleet. There couldn’t be warships still on duty without a crew, but, demobilization couldn’t be held up either.

When the Japanese emperor made his surrender announcement in August 1945, the total manpower of the US Navy hovered around 3,000,000 plus another 400,000 non-active reservists, female WAVEs, and recruits still in training.

In early November 1945, about six weeks after the surrender signing aboard USS Missouri, Congress outlined the first demobilization plan for the US Navy. A minimum of 33% of the fleet’s WWII manpower, about a million men, was to be out no later than 15 February 1946; and of this, 327,000 by Christmas 1945 and 865,000 by New Years Eve. By the end of April 1946, 50% of the wartime manpower would be out. By 1 September 1946, the process would be essentially completed with 3,000,000 WWII veterans mustered out, leaving about 490,000 on active duty in January 1947 including new sailors recruited in the meantime.

In November 1945 Congress set a target of 1,079 active-duty warships to be in service at the end of 1946. This was to include WWII-veteran warships and vessels built in the meantime. While it might sound counter-intuitive, the US Navy had to maintain at least a snail’s pace of new commissionings even as relatively fresh ships were mothballed. This would avoid block obsolescence problems (entire generations of ships simultaneously wearing out) down the road, and would also avoid bankrupting shipyards.

Determining active vs reserve

While WWII was still raging, a small office of the US Navy quietly began planning what the postwar battle fleet might look like. This was kept hidden as not to seem arrogant or callous to the American public.With no knowledge of the Manhattan Project, the team estimated that WWII would end in 1946 (in Great Britain, the Royal Navy felt early 1947 was more likely). The team took into account losses to date, ships under construction, current & future technology and tactical trends, and projected losses during the final invasion of Japan. The team estimated the US Navy would finish the war with a surplus of battleships, cruisers, submarines, and convoy escorts, a parity of aircraft carriers, and a shortage of destroyers and amphibious ships. For carriers, destroyers, and landing craft, the terrible kamikaze poundings during the Okinawa invasion were projected to be much worse as Japan would obviously throw everything at the final invasion fleet.

Above is a chart of the intended (1945) postwar disposition of the fleet’s large combatants.

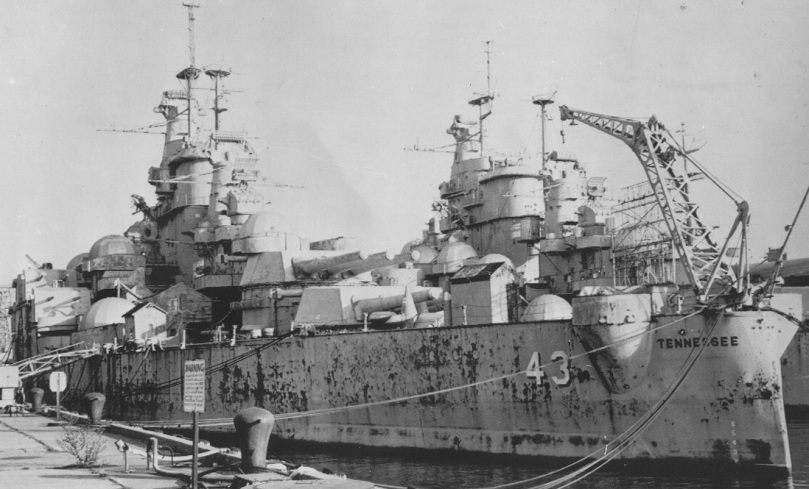

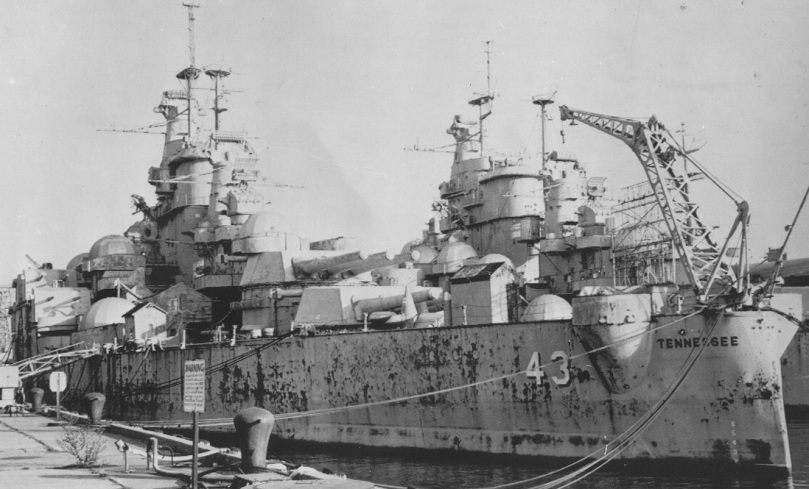

Already during WWII, it had been decided that none of the so-called “standard-style” battleships would be retained on peacetime active duty. All would be placed into reserve or discarded outright. Below is the mothballed USS Tennessee (BB-43), a pre-WWII design, decommissioned in February 1947 and rusting away in reserve on 6 December 1956. None of the “standard-style” battleships were ever reactivated during the Cold War.

Of the remaining ten, six were called “treaty-style” and finally the four very modern Iowa class. For battleships, which had been eclipsed by aircraft carriers and submarines during WWII, it was planned to retain on active service the four Iowas and two of the six “treaty-style”. The two North Carolina class ships were selected, even though they were older than the four South Dakota class, as mothballing all four South Dakotas would remove an entire block of training and spare parts requirements from the active fleet.

Battleships are tremendously expensive to operate in peacetime and even this modest plan unraveled. Both North Carolina class ships went into reserve in 1947. Above are USS North Carolina (BB-55) and USS Washington (BB-56) mothballed at Bayonne, NJ in February 1951. Both had been in reserve for four years at that point and have “igloos” covering their 40mm AA gun positions. Ahead of USS North Carolina is the battlecruiser USS Alaska. None of these ships was ever reactivated. USS Washington was scrapped in 1961, USS Alaska in 1960, and USS North Carolina was made into a museum ship.

One of Grumman’s “too-late cats”, the F7F Tigercat fighter just missed WWII combat. The Tigercat above was aboard the Essex class carrier USS Shangri-La (CV-38) in February 1946, six months after WWII. Capable of operating upcoming jets, the Essex class large aircraft carriers were considered war-winners and formed the core of the active-duty peacetime navy.

Meanwhile the smaller carriers (CVLs and CVEs) were greatly pared in number. Especially in the case of the CVEs, their primary task had been escorting convoys against u-boat wolfpacks in the Atlantic, and there was simply no real role for them in the late-1940s US Navy. Many of these ships were later pulled out of mothballs for conversion into ASW carriers or aircraft transports. Three were later transferred abroad. Above (lower left) is USS Solomons (CVE-67) along with a huge number of other mothballed CVEs at Boston Navy Yard in 1946. USS Solomons was later the first of the mothballed CVEs to be scrapped.

An extreme case (above photo) was the escort carrier USS Tinian (CVE-123), which literally went cradle-to-grave in mothballs. Launched about 48 hours after the Japanese surrender, USS Tinian was completed with leftover wartime funds and ran builder’s trials in early 1946. On 30 July 1946, the US Navy quietly declared the ship “accepted” without ceremony, and USS Tinian was sailed straight into the mothball fleet. The unused USS Tinian sat in reserve for a quarter-century before being scrapped in 1971, never having done anything.

The US Navy finished WWII with a huge surplus of cruisers. With the postwar Des Moines class already started, most went into reserve in the late 1940s. USS Augusta (CA-31) decommissioned ten months after the end of WWII. The post-WWII press release above announced the reinstatement of “dress ship” (flying of all pennants and lights on holidays) a custom of the sea which the US Navy suspended after the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. USS Augusta never returned to service and was later scrapped after 13 years in mothballs.

The two Alaska class battlecruisers were a separate issue. The American concept of battlecruisers differed from the rest of the world. The US Navy designed the Alaskas before WWII as “cruiser-killers”, specifically to hunt down and destroy Japanese fast heavy cruisers. By 1945, their intended prey had already been sunk and their core mission vanished. USS Alaska and USS Guam were almost as expensive as battleships to operate in peacetime. They went into reserve in 1947. Part of the reason they were retained in reserve was political; their Mk8 12″ guns were very expensive to design and build during WWII and were specific only to this class. It would have looked bad to not get return on the taxpayer investment, even if only as a reserve asset. Neither was ever reactivated and both were scrapped in 1960. The photo above shows USS Alaska prior to decommissioning, with her seaplanes already moved ashore.

USS William M. Wood (DD-715) was a Gearing class destroyer launched during WWII but still doing sea trials when Japan surrendered. The Gearing class was the best destroyer design of WWII and quite possibly the best all-around warship class in the world in 1945. Fresh, powerful, and modern; destroyers like USS William M. Wood would form the core of the peacetime escorts and continued in active duty.

The US Navy’s massive amphibious force, the largest the world had ever seen, was greatly dialed down in size. Never again would there be anything like the “Overlord” landings in Normandy in 1944, and there was neither the need for these ships, nor funds to operate them, in active duty. Additionally, some “minor” types like LCMs, LCVPs, LCTs, etc had been built more or less under the assumption that they were semi-disposable, with lifespans not intended to go much past the defeat of the Axis. Above is the medium landing ship LSM-272 in reserve. After Japan’s 1945 surrender, LSM-272 served the occupation fleet then decommissioned in May 1946. The vessel was used as a makeshift mooring barge by US Navy smallboats at San Diego, CA for a while then scrapped in 1948.

With less ships overall, there were less ships per auxiliary to support and the number of auxiliaries, both in active service and reserve, was trimmed. The warship above is USS Vanderburgh (APB-48), a Benewah class self-propelled barracks barge, which commissioned about two months before the end of WWII. With a surplus of these types already on duty, the fresh USS Vanderburgh was placed into reserve at the Mare Island, CA mothball fleet in 1947. The 1960s photo shows the typical “igloos” over the Mk4 40mm guns. USS Vanderburgh never returned to service and was scrapped in Portland, OR in 1969.

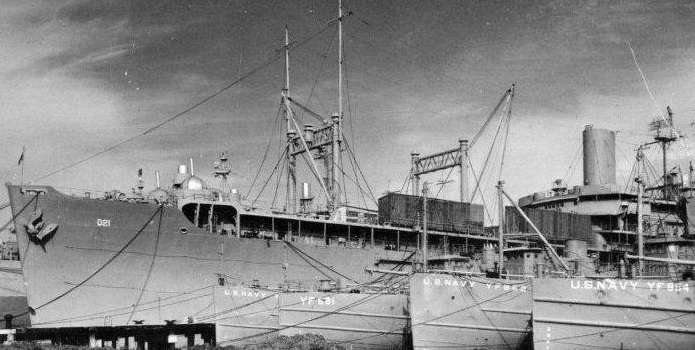

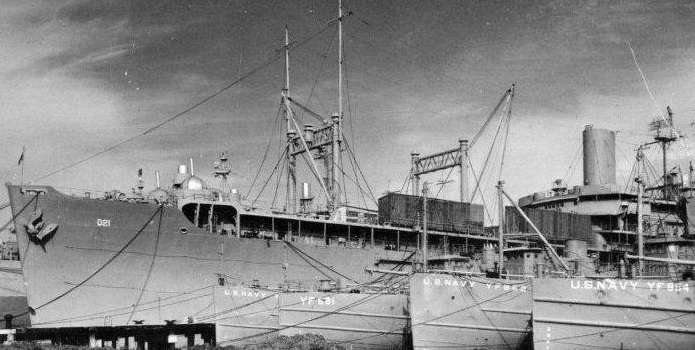

The destroyer tender USS Markab (AD-21) was mothballed at the Orange, TX facility in January 1947. The photo above shows the ship with four mothballed lighters of the Yard & District Craft fleet. The second from right, USS Ensenada (YF-852) was later reactivated and served into the 1980s.

(photo by Larry Cote)

In 1960, USS Markab was reactivated and converted into a repair ship (AR-23), seeing service in the Vietnam War. Decommissioning again in 1969, USS Markab was mothballed at Suisun Bay, CA and scrapped in 1977.

Little was done to preserve surplus WWII naval warplanes. In the 1940s, aviation technology was “turning a generation” every three years or so – consider that the US Navy started WWII with the laughable Brewster Buffalo but finished it with the Grumman Bearcat, in a span of just over four years. A few select types were preserved, such as the SC-1 Seahawk battleship seaplane being vacuum-sealed after WWII. This was for naught anyways, as by the time the Korean War started in 1950, helicopters had replaced catapult planes aboard cruisers and battleships.

Determining reserve vs scrapped

Once the ships desired for active-duty retention had been identified; the remainder had to be split up between those destined for reserve and those to just be discarded. Some choices were easy.With a surplus of modern types, the US Navy had no need for wartime-emergency obsolete holdovers.

Above is a graph showing the overall fleet disposition in 1946. This includes all the smaller types, such as landing craft, subchasers, convoy escorts, tugs, barges, and the such.

The WWI battleship USS Arkansas (BB-33) was, by 1945, old, slow, and thoroughly obsolete. The US Navy’s oldest frontline battleship at the end of WWII, USS Arkansas was decommissioned and sunk as a nuclear target. The remaining New York, Nevada, and Pennsylvania class battleships were also all quickly decommissioned and disposed of, as they would have no role in any future war. The photo above shows the final second of USS Arkansas‘s life; it is the black splotch on the right side of the test “Baker” mushroom cloud at Bikini in 1946. The atomic bomb picked the battleship up like a toy and piledrived it vertically into the seafloor.

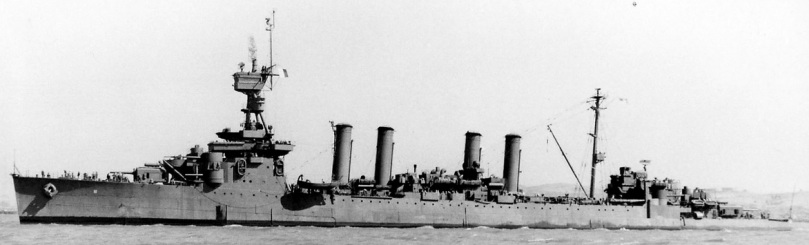

Above is USS Trenton (CL-11) a pre-WWII Omaha class cruiser photographed near the war’s end. Completely obsolete in terms of postwar cruiser tactics, USS Trenton decommissioned three months after the Japanese surrender was signed in 1945 and was sold as scrap for $67,288 in January 1946.

The Sims class destroyers is an interesting example of the rationale used when deciding which ships would be mothballed vs discarded. These destroyers gave excellent service throughout WWII and were always in the thick of battle. By the Okinawa campaign, seven of the twelve Sims class still survived. The US Navy anticipated massive destroyer losses during the planned invasion of Japan, and to that end, it was decided to modernize the remaining seven for service in the invasion and then in the postwar fleet.

The plan was to refit three and then rotate out the other four Sims for their refits. WWII ended while work on the first three was underway. Now with a surplus, not shortage, of destroyers; the US Navy decided to discard the entire Sims class even though there was nothing wrong with them. Eliminating the whole class removed an entire block from the fleet’s training and spare parts burden. The three in refit were given a stop-work order. Literally overnight, the yard workers left one shift trying to get them back to sea as fast as possible, then started the next day’s shift preparing them for scrapping. The other four were expended as nuclear targets at Bikini.

Above (inboard) is USS Roe (DD-418) two weeks after V-J Day. This shows how the Sims class would have been similar in ability to a Fletcher class (alongside) had the project continued. Instead USS Roe was scrapped.

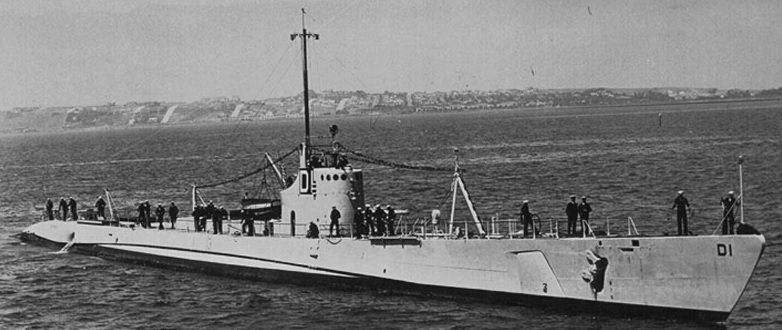

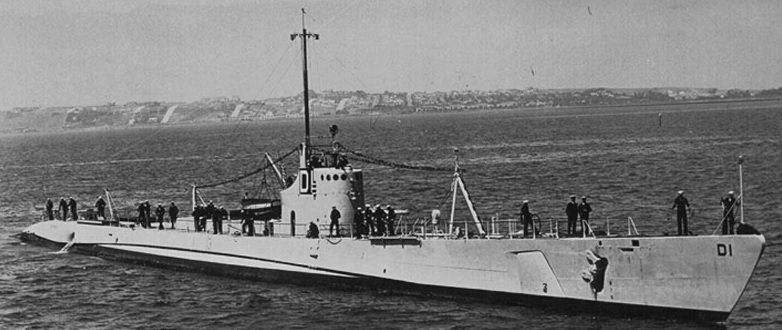

The submarine USS Dolphin (SS-169) commissioned in 1932. USS Dolphin was a “bridge” between the WWI-era subs before, and the Sargo, Tambor, Gato, and Balao classes later of WWII. A distinguishing trait was a watertight hangar for a smallboat; when USS Dolphin was being designed there was concern that unrestricted submarine warfare might later be classified as a war crime. To that end USS Dolphin was intended to surface, dispatch the smallboat to the target ship, and politely offer them the opportunity to surrender before firing torpedoes. After the savagery of WWII that now seems naive, but was the thinking of that time. USS Dolphin did not sink any ships during WWII but served first as a valuable training submarine at Pearl Harbor, HI; then as an instructional hull for the Navy Submarine School at Groton, CT. A submarine like this had no future and there was no point in keeping USS Dolphin in reserve. One of the first subs to go, USS Dolphin decommissioned 28 days after V-J Day and was scrapped.

With the drawdown of the combatant fleet, much of the yard & district support ships that kept it going joined it in mothballs. But there was a limit to how much could be supported in reserve. Some vessels did not make the cut and were scrapped.

The little 1,600 ton nameless drydock YFD-60 had only been completed in 1944. With WWII’s end in 1945, YFD-60 and her sister-ship YFD-61 were at the bottom of the totem pole of floating drydocks. Both decommissioned shortly after the war’s end and were discarded, having seen little use. In the YFD-60 photo above is the drydocked Coast Guard cutter USCGC Pamlico (WPR-57); a veteran of WWI, Prohibition rum patrols, and WWII. USCGC Pamlico was also discarded shortly after WWII.

Another example, above, was USS Zane. Built as a destroyer (DD-337) in 1919, USS Zane was obsolete in that role even at the start of WWII and was unsuccessfully converted into a mine warfare ship (DMS-14) during the war, and then again to a test ship (AG-109) which proved more useful. When WWII ended the US Navy had any number of newer hulls to use as test vessels, and USS Zane was decommissioned eleven weeks after WWII’s end and scrapped.

Of the civilian yachts and fishing trawlers emergency-requisitioned at the height of the u-boat attacks, many were returned to their owners even before WWII ended. The cheery clipping above is from a 1945 issue of All Hands, the US Navy magazine. Chevrons or not, many civilian owners were unhappy at the condition their watercraft were returned in.

Scrapping

For warships in the discard category, usable spare parts were stripped off. Usually (but not always) the main guns were “demilled” by torching the barrel or cracking the breech. The US Navy’s final step for scrapping a WWII warship was estimating what would be recovered, so that an auction minimum could be calculated. Generally in a destroyer there was about 40 tons of recoverable steel, 1 ton of copper wiring, 1 ton of brass, and 3 tons of lead.

WWII-era forward bases in the Pacific

The WWII US Navy had acquired many forward bases, anchorages, and naval airfields across the Pacific Ocean between 1941-1945. In November 1945, Congress shortlisted nine which would be retained or even expanded for the postwar fleet. They were Adak, AK; Kodiak, AK; Pearl Harbor, HI; Balboa, CZ; Apra Harbor, GU; Subic Bay, Phillipines; Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and Manus Island.

This expensive plan never came to fruition. As time passed and things were re-evaluated, most of these bases dwindled. The two in Alaska and one in the Canal Zone remained but in greatly-reduced scope and importance. Iwo Jima was never a key postwar base and was later abandoned. Manus Island, north of New Guinea, was allocated to Australia and was never a postwar US Navy base at all. By the late 1960s, only Subic Bay, Apra Harbor, and of course Pearl Harbor were still of any real importance.

Congress mandated retention of other WWII forward naval bases in lay-up status; in view of a possible future need. These were Wake Island, Midway Island, Truk, Tern Island, and Eniwetok. None of these played any major role ever again. Truk was quickly abandoned, Tern Island naval airstrip was destroyed by a tsunami in 1946, and the others played very minor roles in the Cold War. Eniwetok was used as the staging area for nuclear tests but otherwise unimportant. Midway was reactivated during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, finally being disestablished in 1978 and permanently abandoned in 1993.

The “roll-up”

Millions of dollars of ashore US Navy property was scattered around the world when WWII ended. Congress demanded a genuine effort to recover the taxpayer’s investment, either through use, sale into the civilian economy, or auction as scrap. The Army-Navy Liquidation Commission was established to ensure this directive was obeyed. Navy ashore equipment was divided into three categories:

- No longer needed at it’s current location but able to be economically shipped back to the USA for use, sale, or scrapping.

- No longer needed at it’s current location, and uneconomical to ship back to the USA. US Navy commanders were responsible to seek a nearby Army, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard unit in need of the equipment.

- Unwanted by any branch of the military and uneconomical to ship back to the USA. Gear in this category was to be first offered for sale to allied foreign navies, then to local civilian authorities, and finally, abandoned.

While there was some waste – such as “Million Dollar Point” off Espiritu Santo island where everything from artillery to the construction crane above to unissued Coca-Cola rations was dumped into the ocean – the worldwide “roll-up” was generally an economic success. A case in point was Ulithi. This 85 miles² atoll lagoon could accommodate 1,000 warships including battleships and carriers. Ulithi was the US Navy’s main Pacific forward base. At it’s peak, it briefly displaced Norfolk, VA as the largest naval base on Earth. Ulithi lost it’s importance after Subic Bay was liberated in 1945. As part of the “roll-up”, literally everything at Ulithi was collected and sent back to the USA. The US Navy estimated the total ashore equipment recovered filled the equivalent of six full freighters. By late 1946, barely a trace of WWII remained.

Lend-Lease returns

Almost none of the ships lend-leased to the Allies were retained in reserve. Some were obsolete, many duplicated the abilities of mothballed US Navy ships, and most had seen rough use during WWII. Many had foreign equipment installed and for some, the US Navy lacked a full bibliography of their maintenance records.

Above is HMS Reaper, a British lend-leased escort carrier. Before the lend-lease expired, one of the ship’s final missions was operation “Lusty”, the transport of high-technology ex-Luftwaffe planes captured at the end of WWII to the USA for study. On deck are Me-262 jets, a Ta-152, a Fw-190, a Do-335 Pfeil, and a Ju-388. All are encased in plastic to protect them from seaspray. HMS Reaper decommissioned shortly thereafter. The US Navy had no interest in getting the hull back and Great Britain disposed of it.

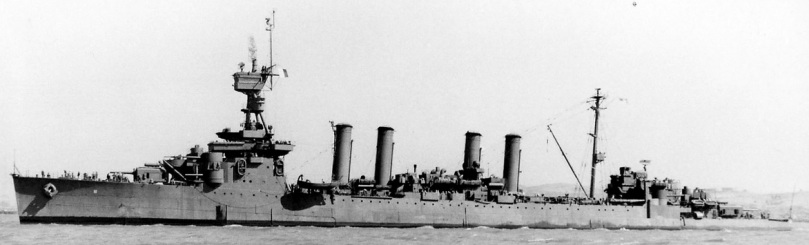

One of the oddest returnees was USS Milwaukee (CL-5). This obsolete cruiser had been loaned to the Soviet Union during WWII. On 16 March 1949, three and a half years after WWII ended, the Soviets returned the cruiser which they had named Murmansk. With sponsoned casemate guns, obsolete turrets, first-generation radar, and worn-out steam engines; the “four-piper” USS Milwaukee was a floating dinosaur. The cruiser was immediately decommissioned and immediately offered as scrap. However for about 36 hours while the paperwork went up the chain of command, USS Milwaukee was briefly, at least on paper, the senior active-duty cruiser in the US Navy.

Planned organization of the reserve fleet and the “divisions” concept

In the US Navy’s numbered fleet system, two “ghost” reserve fleets were formed; the 16th in the Atlantic and 19th in the Pacific.

Each had a number of reserve anchorages. The 16th fleet’s were Boston, MA; Groton, CT; the “Hudson River Group” in NY; Philadelphia, PA; Baltimore, MD; James River, VA; Wilmington, NC; Charleston, SC; the “Florida Group” in that state; Mobile, AL; New Orleans, LA; and Orange, TX. Meanwhile in the Pacific, the 19th fleet had Pearl Harbor, HI; Bremerton, WA; Astoria, WA; Stockton, CA; Suisun Bay, CA; San Francisco, CA; and San Diego, CA.

Not all were the same size, and the facilities were not “balanced” in the sense of having all kinds of warships. For example the Groton, CT facility was almost exclusively submarines, while the Charleston, SC location had a surplus of destroyers.

(The Tongue Point anchorage of the Astoria, WA facility at it’s peak just before the start of the Korean War.)

At each location, mothballed ships were formed into divisions. Each division numbered four to twelve ships, and was always of the same type and (if possible) the same class. The divisions were to be operated as follows:

- For “capital combatants” like large aircraft carriers, newer battleships, large modern cruisers, etc; every ship would have a skeleton crew at the facility assigned to keep the mothballed ship preserved, and also to form the nucleus of a new crew if the ship were reactivated in a national emergency.

- For secondary combatants like light cruisers, destroyers, frigates, LSTs, submarines, escort carriers, minesweepers, etc; only one ship in the division would have a skeleton crew, responsible for all the vessels in the division. These men would divide their time between the division’s vessels. The ship with the crew assigned would in theory, be able to be reactivated in about ten days, while the rest would be in “Ready-30” status, to be reactivated in five weeks or less.

- For minor assets like yard tugs, subchasers, landing craft, barges, lighters, etc; no skeleton crew would be assigned to the division and it’s upkeep would be the responsibility of the base.

The “divisions” concept did not work out as intended. The US Navy’s budgets in 1947, 1948, and 1949 were much smaller than had been envisioned in 1945, and there simply was not enough money for the skeleton crews. By the time of the Korean War, the idea was unraveling and in the mid-1950s was abandoned.