This was a fun post for me, I have blogged before about RADAR , I dealt with ELINT while I was in the service and my specialty was the Soviet Army and East Germans, those were who our threats were. I don't do that stuff anymore and haven't for a very long time, but I did enjoy it immensely while I did it.

Detecting and locating the approaching enemy aircraft during a war is integral in making sure that the troops are prepared in case of enemy assault, regardless of what they had with them— bombs, chemical weapons, maybe paratroopers. It’s great that radar (radio detection and ranging) was invented, thus, making it easier for soldiers to locate exactly where these planes are. Before it was made, however, people had to rely on what was available for us to use: eyes and ears. Just like any other primitive ways that our ancestors used in their time, experiments were done, too, to enable humans to do beyond what our bodies allowed us.

Before radar and all the other machinery inventions before it, the capability of detecting aircraft during the times of war was the responsibility of human spotters. They were often positioned in open fields, shorelines, rooftops of tall buildings, and hills so they could monitor and spot approaching enemy aircraft and send warnings. However, the effectiveness of this method was reliant on many parameters: the eyesight and hearing quality of the observers, their alertness, the visibility of the surrounding atmosphere (if it was raining or foggy), the level of light, as well as the size, color, configuration, and noise level of the aircraft.

Assuming it was the perfect and most ideal conditions and the human spotter was able to detect the aircraft as soon as humanly possible, it would only allow a few minutes for the soldiers to prepare a response before the plane reached their position. Usually, observer networks were placed up far in advance, and information was transmitted through a radio relay network, but the method was still not always reliable.

From mid-World War I until the early years of World War II, the acoustic location was used for passive detection's of aircraft by picking up the noise of their engines. How passive acoustic location worked was that sound or vibrations created by the detected object were analyzed to determine its location. At the same time, horns were used to increase the observer’s ability to localize the direction of the sound. These techniques, during that time, had the advantage as sound refraction allowed them to “see” around corners and over hills.

According to the reports, Commander Alfred Rawlinson of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve first used the equipment as he needed a means of locating the German Zeppelins during cloudy days. He improvised an apparatus made from a pair of gramophone horns that he mounted on a rotating pole.

The instruments were usually made of large horns or microphones connected to the operators’ ears through a tube. Imagine a stethoscope but supersize it. From there, an extensive network of sound mirrors that were used from World War I through the Second World War was developed. These sound mirrors worked with a combination of microphones that had to be moved to find the angle that maximizes the amplitude of the sound. Two sound mirrors at different positions were usually set up to generate two different bearings, allowing the operator to use triangulation to point out the direction of the sound source.

Although the equipment seemed crude by today’s standards, they were able to provide a fairly accurate fix on the approaching planes so guns could be directed at them before they arrived or even when they were out of sight due to low visibility.

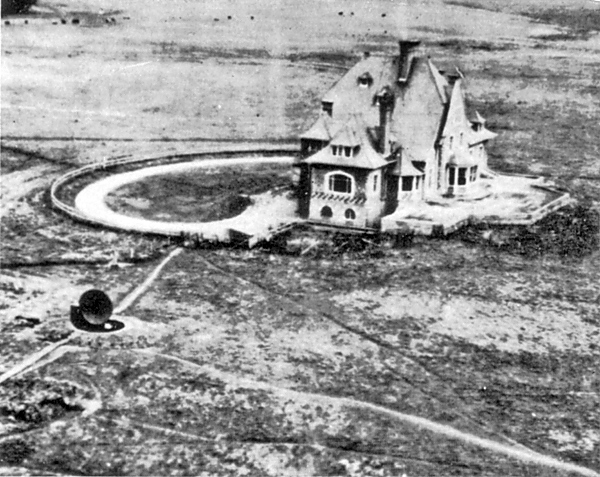

Dover Radar Station during WWII

During the half part of World War II, radar became an alternative to these acoustic location techniques and equipment. Both the United Kingdom and Germany knew that they were working on radio navigation and its countermeasures, known as the Battle of the Beams. Their interest in radio-based detection and tracking led to the use of radar. Britain, however, never really admitted that they were using radar and showed publicly that they were using acoustic location.

The Swingate transmitting station is a facility for FM-transmission in the village of Swingate, near Dover, Kent (grid reference TR334429). For many years there were three lattice towers with a height of 111 metres (364 ft). This station was one of the first 5 Chain Home Radar stations completed in 1936 and was originally designated AMES (Air Ministry Experimental Station) 04 Dover. The FM transmitting antennas are attached to what was the middle tower; microwave link dishes and mobile telephone antennas were spread across all three towers. The south tower was dismantled in March 2010, as a result, only two remain. The Swingate towers no longer have the three cantilever platforms that were fitted originally.

The Sparse construction made it difficult for the Germans to strike the towers and cause any real damage despite the accuracy of their bombers due to the fierce resistance by the RAF and the huge cost that is incurred every time the Germans went after the towers.

In the Battle of Britain, both sides were already using radars and control stations to up their air defense capability. At the same time, the United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan were also developing their own detecting systems. The acronym “RADAR” was not used until 1940, when the US Navy coined the term as an acronym meaning Radio Direction And Ranging. Even after this innovation, the acoustic location stations did not cease operation and acted as a backup to radar. After the war, radar has been so developed that audio aircraft detection equipment was totally obsolete.

At the same time, using sound to accurately detect objects moved from the air to beneath the waves become SONAR, or Sound Navigation And Ranging for submarines and surface vessels to navigate and find targets.