Artist rendering of the proposed Lexington Class Battle Cruisers.

The United States Navy’s only planned battlecruisers, six Lexington class ships authorized by the Naval Act 1916, were cancelled by the Five Power (‘Washington’) Treaty of 1922. Two – Lexington and Saratoga – were completed as aircraft carriers instead. The battlecruisers have often been considered something of a side-issue

for a US Navy that was primarily interested in well-armed and armored

battleships.

In fact, these battlecruisers had a central place in US naval

thinking at the time. Their concept reflected a prevailing US Navy

battle doctrine of ‘aggressive offensive action’. The same style of

thinking was also applied to the designs of the first US ‘Treaty’

cruisers of the early 1920s. And the Lexingtons drew from specifically American tactical naval needs and thinking.

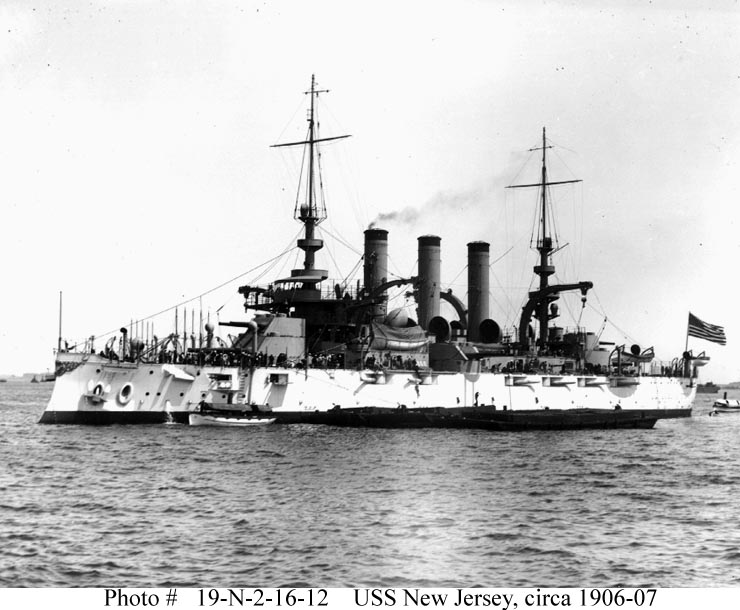

By the last years of the nineteenth century,

however, battleships were gaining medium guns on top of the rest –

literally in the United States, where the medium guns were at times

housed atop the main armament. The rise in fire-power also influenced armored cruiser designs, which

gained displacement and scale of fire-power comparable to second-class

battleships, yet retained greater speed. These developments then fed into emerging thinking about how the design

components – protection, fire-power, sea-keeping, speed, range,

displacement and habitability – could be mixed. Tactics and technology,

in short, were entwined; and a conceptual revolution involving both was

well under way by 1901-02.

This thinking was shared across the Admiralty. However, Fisher also felt the heavy gun had won the gun-vs-armor race. Because ships were going to be size-limited, primarily for cost reasons, he felt it better to put displacement into speed and massive guns. Heavy armor was unnecessary. So too was anything other than minimal lighter weaponry. As Norman Friedman observes, by 1915 Fisher even opposed the heavier secondary guns required for anti-destroyer work.

The crucial point is that Fisher felt that all heavy construction should go into such faster ships. As early as 1902 he was arguing that there was little distinction between armored cruisers and battleships. ‘The Armored Cruiser…is a swift battleship in disguise’. And this is the point: to Fisher, the evolved armored cruiser became a replacement for the battleship. As First Sea Lord from late 1904 he put a good deal of effort into trying to persuade the rest of the Admiralty and the Cabinet to agree. In a way, he had a point. A fast ship with monster guns could keep a safe distance while dealing out massive blows. Fisher was not the first to come up with this idea: the Italian naval designer Benedetto Brin had explored it in the 1870s.

In the end, Fisher never convinced either the Admiralty or the British government to authorize battlecruisers in number. The original three were a windfall; the 1904-1905 building program called for one battleship and three armored cruisers on the basis that Britain was under-strength in the latter. Before any were laid down, Fisher’s Committee on Designs produced the Dreadnought and its cruiser homologue, the Invincible – and so Britain got one all big-gun battleship and three all big-gun armored cruisers, later dubbed battlecruisers. But aside from the 1908 ‘naval panic’ with the ‘contingency’ program approved in August 1909, only one battlecruiser was then usually authorized in each annual schedule, and the type was abandoned altogether in the 1912 program Battlecruisers were not re-visited until Fisher’s return to the Admiralty in 1914.

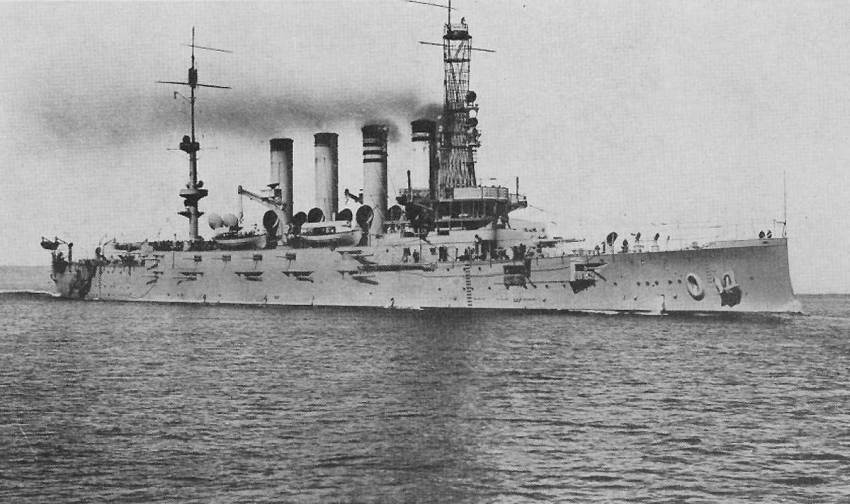

But in any case, while professional opinion within the US Navy was better-defined than in government – thanks in part to the Naval War College– thinking leaned towards heavily armed and armored battleships with moderate speed but good unrefuelled range. This was largely to meet US strategic commitments of the day, which focused on trans-Pacific interests. Such ships were intended to form a solid battle-line, to which the enemy would have to come if they were to defeat the United States at sea. This influenced the occasional foray into faster vessels. In 1910, the Chief Constructor of the Bureau of Construction and Repair, Rear-Admiral Washington L. Capps, organized six potential designs for fast all-big-gun armored cruisers, which had relatively modest speed by the British battlecruiser standards of that period – 25.5 knots – but with armor closer to contemporary US battleship scale. These were rejected by the General Board, which felt such ships were cruisers, and what the US Navy needed were more battleships.

Yet, within a few years, the US Navy was indeed pursuing the idea of battlecruisers – and, furthermore, battlecruisers with the massive fire-power, remarkable speed and thin armor that Fisher thought ideal. But this was for wholly US-developed motives, which diverged from Fisher’s reasoning. Proposals along the way included a surreal 1,250 foot long monster displacing over 60,000 tons. We shall pick up the story of how that happened, and how the latest mainstream British ideas about heavier armor then infused themselves into US battlecruiser thinking, in the next article

Jutland showed the fallacy in Fisher's battlecruiser concept .

ReplyDeleteThe Germans did it better - thicker armor , slightly smaller guns , not quite as fast - but able to dish it out just fine , and infinitely more survivable .

The Lexingtons would have been enormous white elephants had they not been converted into carriers . The Japanese also recognized the flaw in the battlecruiser concept , rebuilding the Kongos as ( very useful ) fast battleships , and the Akagis as carriers .

Even the Brits rebuilt their Courageous "light" battlecruisers as carriers . Sadly , Hood and Repulse were not , and went on to the typical fate of a battlecruiser in combat .

Hey JerseyGirlAngie;

DeleteYep you are correct, while reading and putting this article together, I was thinking of the Hood, not the Repulse though. The sad thing was that HMS Hood was due for an extensive refit that would have corrected most of the armor deficiencies that the ship had. The British Admiralty knew of the flaws of their battle cruisers, after Jutland, it was apparent. I remember reading somewhere an admiral asked "What is the matter with our battlecruisers?".

Jersey beat me to it. And Billy Mitchell's actions had a bit to do with the change in thinking... Just sayin...

ReplyDelete