I am what is called a "old school unionist". Unions served a purpose when they first started for the working conditions in the average facility was horrible, people were getting maimed and killed and the kids working the factories at a young age to help out their families but they were not able to go to school and having to work, with little education guaranteed them being virtual slaves. My experience with unions was that I was a "shop steward" for the automotive union. I got the job by my peers because I knew the contract backward and forward and I would go toe to toe with any one. I was the only republican to hold union office. A bunch of us found a home in the "America First" movement of Donald Trump I found my experience interesting, with few exceptions I found myself working with the same group of people, they wanted to get paid but not work. I used a formula, 5% of the workforce utilized 95% of my time as they gamed and played the system. I heeded my oath of office to do the best I could and I did, I was successful. I would have the rank and file members always complain that "the union are saving the sorry asses." And I agreed. I was an employee and a Ford Stockholder and I wanted them gone but as a union rep, I had to do the best I could and I did. I almost wished the union was self policing and got the sorry asses gone on their own. I would have the same slackers tell me that "Ford owes me a job", and when I go outside in the parking lot, I would see the latest offering from the Japanese companies. I would then ask the dirtbags " what about a Ford? their response was "F*ck Ford, it be my money." I would then call them" a hypocritical 2 face suns of bitches." They would then threaten to whip my ass, I would reply "if you feel froggy, jump to it." They would complain to the chairman about me but I never got any complaints from him. What I meant by an "old school unionist" was that the union was our balance against the corporations, I don't agree with government unions. Walther Reuther one of the founders of the UAW considered a government union to be incorrect. In the traditional relationship, the union and company knew how much the other can stand and still pay and stay in business. Contrary to popular belief, the unions don't want the company to go out of business for it is the livelihood of their members....Little Debbie and Yellow Trucking not withstanding. With the government unions, the people representing the "company" are politicians, they don't feel the pain for their decisions. The decisions are then pushed on the communities and there is no check and balance. Walther Reuther believed in community and the community would pay the freight for the negotiated contract between the government unions and the politicians and he knew that it would be lopsided.

Most of the world marks Labor Day on May 1 with parades and rallies. Americans celebrate it in early September, by heading to the beach or firing up the grill. Why the discrepancy? Here’s a hint: The answer would have been a great disappointment to Frederick Engels.

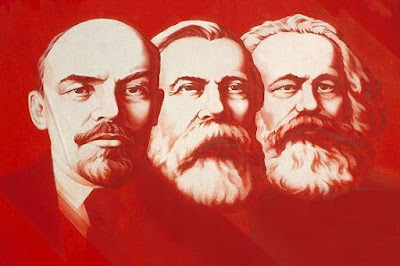

Engels, the co-author of The Communist Manifesto, had high hopes for May Day, which originated in the United States. When the socialist-dominated organization known as the Second International jumped on the American bandwagon and adopted May 1 as International Labor Day, Engels confidently expected the proletariats of Europe and America to merge into one mighty labor movement and sweep capitalism into the dustbin of history.

Things didn’t work out that way, of course, and the divergent Labor Day celebrations are part of the story.

May Day’s origins can be traced to Chicago, where the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, under its leader Samuel Gompers, mounted a general strike on May 1, 1886, as part of its push for an eight-hour work day. On May 4, during a related labor rally in Haymarket Square, someone threw a bomb, which killed a policeman and touched off a deadly mêlée. As a result, four radical labor leaders were eventually hanged on dubious charges.

In 1888, Gompers’s union reorganized itself as the American Federation of Labor, and revived its push for the eight-hour day. Gompers laid plans for a strike to begin on May 1, 1890–the fourth anniversary of the walkout that had led to the Haymarket affair. Meanwhile, in Paris, a group of labor leaders were meeting to establish the Second International. To these Europeans, the executed Chicago radicals were revered martyrs. In an act of solidarity, the Second International set May 1, 1890, as a day of protest.

Engels was thrilled. “As I write these lines, the proletariat of Europe and America is holding a review of its forces; it is organized for the first time as one army,” he wrote on the first May Day. “The spectacle we are now witnessing will make the capitalists and landowners of all lands realize that today the proletarians of all lands are, in very truth, united. If only Marx were with me to see it with his own eyes!”

The first May Day was deemed a success, so the Second International adopted it as an annual event. And for a few years, it seemed as though May 1 might be on the way to becoming a rallying point for socialists in America, as it was elsewhere. The Panic of 1893 touched off a national wave of bankruptcies that plunged the nation into a deep depression–and depressions generally push workers toward radical solutions. Things came to a boil with the Pullman Strike, which erupted in Chicago in May 1894. The striking Pullman Palace Car Co. workers quickly won the support of the American Railway Union, led by Gompers’s rival Eugene V. Debs. Railroad traffic in much of the country was paralyzed.

President Grover Cleveland, a conservative Democrat, was determined to squash the strike. But he did not want to alienate the American Federation of Labor, which was not yet involved in the Pullman dispute. Moreover, 1894 was a midterm election year, and the Democratic Party could ill afford to be seen as an enemy of labor. Cleveland and the Democrats hit upon a possible solution: They would proclaim a national Labor Day to honor the worker. But not on May 1–that date was tainted by its association with socialists and anarchists. Fortunately, an alternative was at hand.

Back in September 1882, certain unions had begun to celebrate a Labor Day in New York City. By 1894, this event was an annual late-summer tradition in New York and had been adopted by numerous states, but it was not a national holiday. Nor was it associated with the radicals who ran the Second International, and who liked to run riot on May Day.

On the contrary, the September date was closely associated with Gompers, who was campaigning to have it declared a national holiday. Gompers opposed the socialists and was guiding the AFL toward a narrower and less-radical agenda. Gratefully, Cleveland seized upon the relatively innocuous September holiday as a way to reward labor without endorsing radicalism. On June 28, 1894, he signed an act of Congress establishing Labor Day as a federal holiday on the first Monday of September. (He made a point of sending the signing pen to Gompers as a souvenir.) Less than a week later, the president sent federal troops to Chicago. Gompers refused to support the strike, which soon collapsed.

With his union in ruins, Debs went into politics, but his Socialist Party ultimately failed to catch on as America’s party of the left. Organized labor did not regain its momentum until the 1930s–and by that point, Gompers’s September holiday had been institutionalized as America’s Labor Day. May Day, meanwhile, had become the occasion for big annual parades in Moscow’s Red Square, which did not improve that holiday’s reputation in the United States.

May Day today is well established in most of the world as International Labor Day. May 1 also remains a traditional date on which leftists and anarchists of various stripes take to the streets to demonstrate their scorn for capitalism. But America, which has proved impervious to socialism, still celebrates Labor Day in September–and not by marching. AFL officials in New York long ago gave up holding their annual parade on Labor Day itself, because it could not compete with the prospect of a three-day weekend. The parade in recent years has been held on the following Saturday, and even so has been sparsely attended. This year, it has been canceled altogether.

Only 12% of the U.S. workforce belongs to a union these days, down from a peak of 33.2% in 1955. But whether they belong to a union or not, most Americans still have to work, so they appreciate a day off–and they prefer to spend it by relaxing, rather than storming the barricades.

On this Monday Music. I am going with "Allentown" from Billy Joel, I remember a line from the song, "The jobs went away and the union people crawled away" this happened when in the video it showed a worker getting his pink slip while in the shower. I thought about this when my job went away at Ford Motor Company.

Don't get me wrong, I understand why Ford did what they did and they treated us good in a really bad situation. I was the only republican to hold union office, I was a heck of a good shop steward. The rank and file knew it, I didn't hide it, and half of them voted for the GOP despite the union recommending anybody democrat. I had my own issues with the democratic party, even back then, they treated the UAW as an ATM, mention "worker platitudes" and they would take our money, but they were beholding to the environmental movement. and I knew if the environmental groups had their way, my job would be gone. Well it went away anyway. but it was for different reasons.

I got lucky, I got hired by a local airline and am a chemtrail technician now and doing very well, unlike many of my Ford peeps, they didn't do so well. It was difficult making the adjustments. Even now I am sensitive to the subject of "Outsourcing".

.

"Allentown" is a song by American singer Billy Joel, which first appeared on Joel's The Nylon Curtain (1982) album, accompanied by a conceptual music video. It later appeared on Joel's Greatest Hits: Volume II (1985), 2000 Years: The Millennium Concert (2000), The Essential Billy Joel (2001), and 12 Gardens Live (2006) albums. Also, it was featured in Hangover II (2011) "Allentown" is the lead track on The Nylon Curtain, which was the seventh best-selling album of the year in 1982. The song reached #17 on the Billboard Hot 100, spending six consecutive weeks at that position and certified gold. Despite the song placing no higher than #17 on the weekly Billboard Hot 100 chart, it was popular enough to place at #43 on the Billboard year-end Hot 100 chart for 1982.

Upon its release, and especially in subsequent years, "Allentown" has emerged as an anthem of blue collar America, representing both the aspirations and frustrations of America's working class in the late 20th century.

The song's theme is of the resolve of those coping with the demise of the American manufacturing industry in the latter part of the 20th century. More specifically, it depicts the depressed, blue-collar livelihood of residents of Allentown, Pennsylvania and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in the wake of Bethlehem Steel's decline and eventual closure. Joel witnessed this first-hand while performing at the Lehigh Valley's numerous music venues and colleges at the start of his career in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The introductory rhythm of the song is reminiscent of the sound of a rolling mill converting steel ingots into I-beams or other shapes. Such a sound was commonly heard throughout South Bethlehem when the Bethlehem Steel plant was in operation from 1857 through 1995.

When Joel first started writing the song, it was originally named "Levittown", after the Long Island town right next to Hicksville, the town in which Joel had grown up. He had originally written a chord progression and lyrics for the song, but struggled for a topic for the song. Joel remembered reading about the decline of the steel industry in the Lehigh Valley, which included the small cities of both Bethlehem and Allentown. While the steel industry was based in Bethlehem with none of it in Allentown, Joel named the song "Allentown" because it sounded better and it was easier to find other words to rhyme with "Allentown." Although Joel started writing the song in the late 1970s, it wasn't finished until 1982.

A year after the song was released, the mayor of Allentown sent a letter to Joel about giving some of his royalties to the town. Mayor Joseph Daddona, who sent the letter, said it would help for scholarships for future musicians. On January 20, 1983, the letter was mailed to Joel, and a local paper published an article on the subject the next day, quoting Daddona as saying: "Not only would this fund be a great way to share a tiny part of your good fortune to others in Allentown, it would also help keep alive the 'Allentown' song and the Billy Joel legend (which you've already become here)."

When Joel performed the song in Leningrad during the concert recorded and later released as Концерт, he introduced the song by analogizing the situation to that faced by Soviet youths: "This song is about young people living in the Northeast of America. Their lives are miserable because the steel factories are closing down. They desperately want to leave... but they stay because they were brought up to believe that things were going to get better. Maybe that sounds familiar."

The video, directed by Russell Mulcahy and featuring choreography by Kenny Ortega, was in heavy rotation on MTV during 1982 and 1983. The original version of the video features partial male nudity when male coal workers are taking a shower at the beginning, but that part was edited when it aired on MTV. (Although it has aired uncut on both VH1 Classic and MTV Classic in recent years.)

Unions are like a lot of things. At the beginning they are good, often necessary. But it seldom takes long before they mutate into something nasty, evil and corrupt. Unions now are essentially slush funds for corrupt gang bosses. They drive costs of everything through the roof and eventually destroy companies driving production offshore. Now unions do far more harm than good.

ReplyDeleteHey Daniel,

ReplyDeleteI tend to agree, THey still serve a purpose, but there is a lot of corruption associated with the unions and a lot of it is justified. My biggest beef with the unions is how beholden they are to the democratic party, much to the members detriment.