The Minuteman I ICBM, or intercontinental ballistic missile, was a globe-spanning weapon with nearly ten times the destructive capacity of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima at the end of World War II, and in 1974, America successfully launched one out of the back of an airborne C-5 Galaxy.

As if lobbing an 87,000-pound nuclear payload out the back of an aircraft in flight wasn’t a dramatic enough undertaking in itself, the team responsible for history’s only air-launched ICBM were also under a strict deadline and potentially apocalyptic pressure. While their efforts could have resulted in a new approach to leveraging America’s nuclear arsenal, actually fielding a new capability may not have been the real aim of the program. Instead, the entire effort may have really been about sending a message to the Soviet Union before entering into a new round of disarmament talks.

In July of 1945, the United States conducted the first-ever atomic bomb test explosion, ushering in the nuclear age with a blast equivalent to 25,000 tons of dynamite. Four years later, in 1949, the Soviet Union would follow suit, shifting the balance of power around the globe, and setting the stage for a decades-long nuclear staring contest that, to some extent, would survive even the collapse of the Soviet Union itself.

Nuclear posturing had become an integral facet of the ideological conflict between the American and Soviet governments by 1974, with each nation working tirelessly to field new means of leveraging or delivering atomic, and then thermonuclear, weapons. The United States took the technological lead, fielding a massive arsenal of advanced weapons for their time, but what the Soviet juggernaut lacked in scientific accomplishment, it made up for in volume. By 1974, the Soviet Union had all but eliminated America’s technological advantage by simply fielding more of their slightly less advanced weapons.

The truth is, the number of warheads in each nation’s armories was a largely moot point by the time Secretary of State Henry Kissinger began coordinating with his Soviet counterpart for 1974’s Strategic Arms Limitations talks. If America and the Soviet Union were to go to war, the collective onslaught of the two nation’s arsenals would be enough to destroy all life as we knew it. This understanding, known as Mutually Assured Destruction, has been credited by some as the selfish cynicism that has–thus far–saved the world, with each nation knowing that to incite a nuclear war would be to invite one’s own destruction.

But MAD (as the concept is sometimes derisively known) is predicated on maintaining that destructive balance between states, and in the 1970s, the United States had grown seriously concerned that MAD’s equilibrium was beginning to give way. America had long since transitioned to leaning on ICBMs as their primary means of nuclear weapons delivery, but America’s Minuteman ICBM silos were stationary targets with known locations the Soviets could intentionally target in a first-strike offensive.

The Soviets, on the other hand, often leveraged mobile missile launchers, ICBM-firing trains, and even experimented with using giant helicopters to relocate their missiles quickly, to prevent the U.S. from finding and targeting them.

So as Kissinger prepared the meeting with General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Leonid I. Brezhnev, to discuss a joint reduction in arms, he was facing the uncomfortable reality that his opponent had the upper hand. If the Soviets managed to wipe out America’s silo-based nuclear arsenal, it would be extremely difficult to hold up the “mutual” part of the world’s assured destruction with the nation’s nuclear bombs and still fairly-new submarine-launched ballistic missiles.

Kissinger needed to re-balance the nuclear scales before the meeting with Brezhnev, and it fell to the men of the Aeronautical Systems Division at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base to do it.

If the Soviets knew where America’s Minuteman ICBM silos were, the Pentagon decided they needed to find a way to keep the missiles on the move, but merely moving the nukes wasn’t enough. They had to be able to launch them from new locations as well. With multiple options on the table, it wasn’t long before the idea of launching an ICBM from the back of America’s massive new cargo transport, the C-5 Galaxy, bubbled to surface. It was indeed crazy, but crazy wasn’t at all uncommon throughout the Cold War.

Carrying massive payloads was quite literally baked into the C-5’s DNA right from the start of its development. It was born out of the Air Force’s CX-LHS program aimed at fielding an aircraft large and powerful enough to carry America’s newest tanks at the time, the 30-foot long, 50-ton M60 Patton. When they were done, they had an aircraft that could carry two of them 5,300 miles without refueling. The aircraft offers an astonishing 34,734 cubic feet of cargo space, with the cargo bay itself stretching further than the distance of the Wright brother’s entire first flight, at 121 feet.

Perhaps most astonishing of all, the C-5 could carry more than 120,000 pounds inside that massive cavity and still get off the ground. That’s nearly twice the payload capacity of the massive B-52 Bomber or three times that of America’s stealth heavy payload bomber, the B-2 Spirit.

Technically speaking then, the 87,000 pounds of intercontinental ballistic missile and its accompanying gear would be a walk in the park for the mighty Galaxy, but there was more to it than simply getting off the ground. In order to give Kissinger the edge he needed, they had to prove the missile could really launch after the cargo plane released it.

With just 90 days before the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks were set to begin, the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Office (SAMSO) quickly gathered a slew of engineers, aviators, and other subject matter experts from within the military and beyond. The group immediately set to work, pouring over the C-5 Galaxy and LGM-30 Minuteman 1 schematics, looking for reasons the concept could work, or why it couldn’t.

“A couple of our engineers got called to the Pentagon on a Saturday and were asked if it could be done,” Pat O’Brien, an engineer who worked on the program at Wright-Patterson Air Base later recounted.

The most conspicuous challenge was the drop itself. While the C-5 had successfully dropped loads as heavy as 164,000 pounds in the past, the loads had always been divided into four drops, limiting each to around 41,000 pounds. Each drop was conducted by opening the rear doors and deploying drag parachutes out the back of the payload. The sled carrying the load is then unlocked, allowing the parachutes to pull the load safely straight out the back of the plane.

While a large drop might measure 28 feet under normal circumstances, the 87,000-pound Minuteman 1 payload (including its sled), with its three-stage rocket engines, guidance control section, and reentry vehicle stretched over 57 feet. If the chutes failed to successfully drag the load all the way out of the aircraft, the C-5 would become unbalanced and uncontrollable, resulting in a crash. If the nose of the missile tipped too far downward on its way out, the back of the missile would catch the top of the C-5, trapping it and, again, causing a crash. The only way it could work is if everything went exactly according to plan.

“The assessment was that there was a risk, a moderate technical risk, but that we could do it,” O’brien added.

Under normal circumstances, such a dangerous enterprise would have called for a slower, more methodical approach, but there wasn’t time for that. In fact, as testing began and failures started to occur… the program pushed ahead anyway.

“We didn’t realize at the time it was for the SALT talks [Strategic Arms Limitation Talks], but we knew they wanted it done in a certain number of days,” O’brien said.

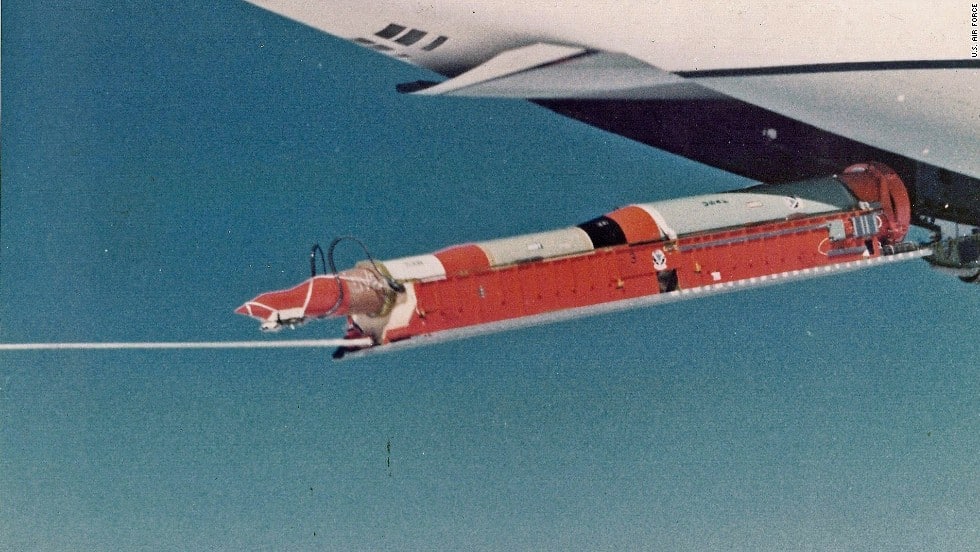

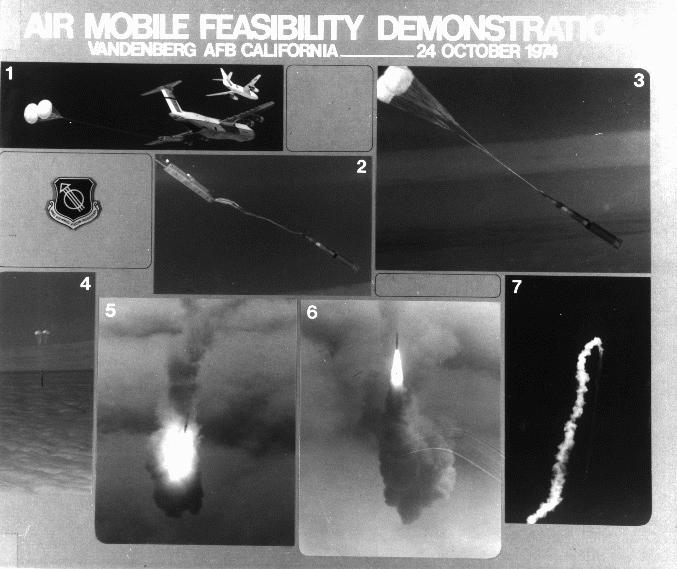

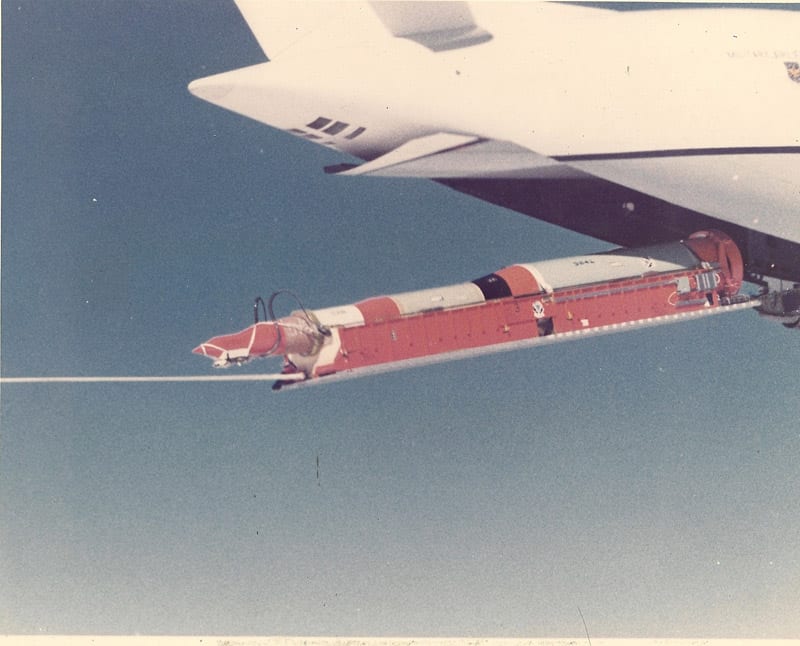

A total of ten test flights were planned, with the first seven dedicated to deploying increasingly heavier and longer payloads and the final three with real missiles; only the last of which would actually ignite its first stage engine. Two C-5 Galaxies were assigned the task of carrying out these flights, one with the registration number 69-0027 would deploy test loads and provide backup for another C-5, registration number 69-0014, which would deploy the live missile in the final test.

While none of the dropped missiles would be carrying a nuclear warhead, the task was nonetheless fraught with danger. Dropping 87,000 pounds from an C-5 would rapidly shift its center of gravity and send the plane lurching upward and forward almost instantly. If the pilots failed to retain control, even a successful drop could result in catastrophe. And the danger for the crew in the unpressurized rear-cabin, riding alongside 43,500 tons of armageddon, was even greater. In fact, they had to wear personal oxygen tanks to withstand the thin air as they prepared the payloads for deployment and, at least once, had to resort to emergency measures to do so.

In order to ensure the C-5 survived launching the ICBM, it would deploy the weapon at an altitude of 20,000 feet using parachutes attached to its nose to orient it upwards. As the missile left the aircraft, a timed fuse on the first stage motor would begin the countdown, igniting the missile’s engine as it fell to 8,000 feet, arresting its downward momentum and sending the continent-spanning weapon off to its far-flung target. For the purposes of the test, however, only the first stage engine would fire as a proof of concept.

On September 6, 1974, the first test drop of a 45,000-pound payload was successful, with a second success just four days later. The following test, which successfully dropped a 54,650-pound payload set a world record for a single drop, though the record would only last until their next test with a 66,000-pound drop.

That test, however, would end in failure, as the payload’s platform tore through the recovery parachutes, allowing the load to free-fall to the ground. The issue was resolved for the following test, switching to a platform that would hang vertically, more like the missile would.

From there they moved up to an 87,320-pound platform payload–a total weight even greater than the missile and platform to come, and for a time to come, the heaviest single payload ever dropped by an aircraft. The test was essential to proving the efficacy of the concept… and unfortunately, the test was nearly a catastrophic failure.

The single 32-foot extraction parachute failed to pull the load cleanly from the aircraft, leaving it not quite stuck, but moving very slowly out the back, creating exactly the sort of dangerous situation the aircrew knew could lead to a crash. Fortunately, the payload eventually fell clear, but it had been the second failure in just six drops. A 33% failure rate, with one of those failures during the only test with a similarly weighted payload to a real missile, might have been enough to prompt further testing in most programs, but time was running out.

The team decided to move forward to missile testing, adding a second 32-foot extraction parachute to hopefully resolve the problem.

On October 24, 1974, one month before the Vladivostok Summit and continued arms control talks were to take place and one month after the nearly disastrous payload test, the C-5 numbered 69-0014 left the runway at Hill Air Force base with thirteen men and one live LGM-30 Minuteman I intercontinental ballistic missile onboard. The group included Lockheed’s test pilots, a flight engineer, two flight test engineers, a pilot from the Air Force Test Pilot Center, two men from 6511th Parachute Test Group, another engineer responsible for the missile guidance system, and a representative from the Minuteman’s manufacturer, Boeing.

In the back, Chief Master Sergeant Elmer Hardin and Senior Master Sergeant Jim Sims wore their personal oxygen tanks and sat on either side of the 56-foot missile as the C-5 soared out over the Pacific.

“We were checking the rails to make sure the locks were out, and we had a 10-minute warning to make sure the extraction chute was hooked up properly and that the safety line ran through the extraction cable mechanism,” Hardin recalled.

At eight minutes before the drop, the rear cargo-bay doors opened, exposing the nose of the missile to the high altitude Pacific air. Sims pulled the safety plug from the Minuteman and replaced it with a green one to indicate that the weapon was armed to fire. As the countdown approached zero, he armed the locks that would release the missile from its sled-like cradle just as it prepared to ignite its engines.

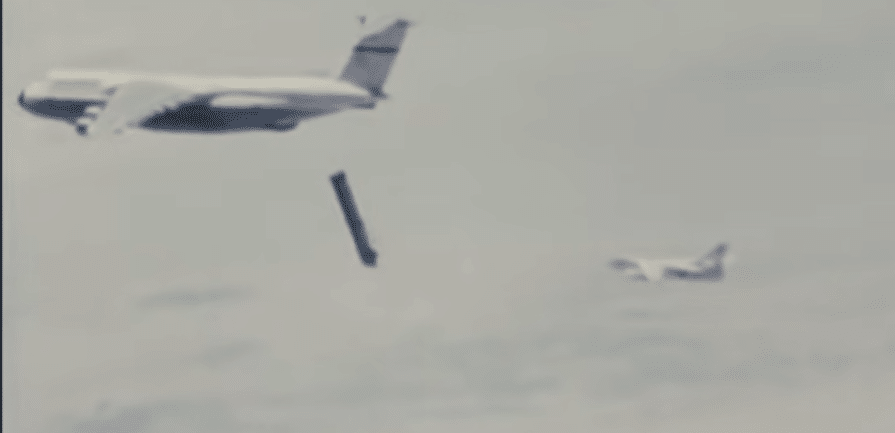

When the clock hit zero, the two 32-foot parachutes deployed, and smooth as could be, pulled the 87,000 pound ICBM and sled from the C-5 as though it was what the aircraft was always meant to do.

“We just did a checklist, opened the doors in flight and away she went,” Sims recalled. “It was picture perfect.”

The C-5 was traveling at around 180 miles per hour when the ICBM dropped, and the sudden shift in weight sent the plane lurching upward and forward, now suddenly producing much more thrust and lift than was required for the C-5 to hold its course. The pilots expertly countered the shift, keeping the aircraft steady.

“It was like dumping out a wheelbarrow full of water,” Sims said. “We gained some forward motion, but [the pilots] had control of that. It was very smooth.”

The two men walked to the edge of the loading ramp, watching the massive missile drop, held upright by a bouquet of parachutes struggling against its immense weight. For an instant, they worried that the missile’s engine wouldn’t fire as it continued to fall some 12,000 feet. Then they saw a flash of light emerge from beneath the ICBM.

“I saw it fire. All at once there was this big ball of fire. That burn stopped the missile from falling and it came straight up,” Hardin recalled.

“We were at 20,000 feet and it passed us. It looked like a giant pencil. It was a pretty amazing thing to see.”

The first stage engine of the Minuteman I screamed through the sky to 30,000 feet, ten thousand feet above the C-5 as it flew away. Then, when the missile’s second stage would usually fire to continue the weapon’s trajectory, the burn ended, and the missile fell safely into the Pacific.

They had done it, and according to Sims and Hardin, they were even briefed that Kissinger felt he’d been given the advantage he needed as he went into talks with the Soviets. That assertion was later substantiated by a Federation of American Scientists report on air launched ballistic missiles, released many years later.

The effort to launch an ICBM from a C-5 Galaxy was anything but discreet. While the U.S. Air Force had often been tight-lipped about nuclear weapons programs, officials were happy to discuss the Air Mobile Feasibility Demonstration. One could contend that the openness was intentional to ensure Brezhnev and the rest of the Soviet government were aware of what was a genuinely monumental strategic shift between the nuclear powers.

Not only did the United States have more advanced nuclear weapons than the Soviet Union, but now they could deploy ICBMs from practically anywhere. Intercepting an ICBM means doing hihgly complex math based on launch location and trajectory to deploy a kinetic interceptor. With no way to pinpoint launch location, not only could the Soviets not take out these ICBMs in a Soveit first strike, but they also couldn’t stop them if America were to choose to take on the role of the aggressor themselves.

In an academic paper submitted to the Aerodynamic Deceleration Systems Conference in November 1975, one year after the tests, two officials from the Air Forces Aeronautical Systems Division, Daniel J. Kolega and James E. Leger, used the data collected from the tests to confirm the viability of air-launched ballistic missiles, including intercontinental ones.

Even more astonishing, they claimed the C-5A could potential launch multiple missiles in a single flight, which could be possible considering the aircraft’s massive payload capabilities.

“The tests also indicated that the C-5A has the capability of launching a missile that is

significantly heavier that the Minuteman I and that multiple Minuteman I airdrops are also possible,” they wrote.

Today’s C-5M Super Galaxy, in fact, can carry payloads of upwards of 285,000 pounds, more than enough to carry three modern Minuteman III ICBMs at once… if this concept were ever put into service, that is.

But that might actually be why this program, despite being considered a success, was quietly shelved after the conclusion of the 1974 summit. What was meant by the Americans to be a second-strike fail-safe to eliminate a Soviet advantage had also produced an incredibly daunting first-strike capability.

Introducing this new un-answerable first-strike capability into the delicate nuclear ecosystem of mutually assured destruction could have been enough to destabilize the balance between nations, and in a worst-case scenario, could even prompt the Soviets to initiate an attack while the U.S. was still vulnerable.

Or maybe all this effort was ever about was giving Henry Kissinger the edge he needed when meeting with his Soviet counterpart

Wow. that would have leveled a lot of playing fields. I wonder if todays NASA and Air Force could pull that off.

ReplyDeleteMachinations within machinations... LOL

ReplyDelete