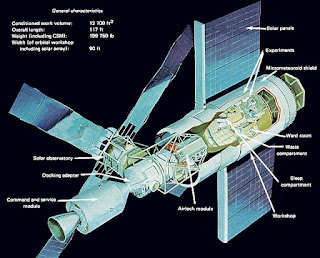

Skylab America's first experimental space station, Skylab, was designed for long durations. Skylab program objectives were twofold: To prove that humans could live and work in space for extended periods, and to expand our knowledge of solar astronomy well beyond Earth-based observations. The program was successful in all respects despite early mechanical difficulties. Skylab was launched into Earth orbit by a Saturn V rocket on May 14, 1973. Through the use of a "dry" third stage of the Saturn V rocket, the station was completely outfitted as a workshop area before launch. Crews visited Skylab and returned to Earth in Apollo spacecraft. Three, three-man crews occupied the Skylab workshop for a total of 171 days and 13 hours. It was the site of nearly 300 scientific and technical experiments, including medical experiments on humans' adaptability to zero gravity, solar experiments and detailed Earth resources experiments. The empty Skylab spacecraft returned to Earth on July 11, 1979, scattering debris over the Indian Ocean and the sparsely settled region of Western Australia.

Part II - Life on Skylab | Part III - The Legacy of Skylab

It's been three years since the first human inhabitants took up residence aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Since then, the ISS has been home to eight resident crews who have performed fantastic research in the microgravity of Earth orbit. But none of this would have been possible without America's first space station: Skylab. From its launch on May 14, 1973, until the return of its third and final crew on Feb. 8, 1974, the Skylab program proved that humans can live and work in outer space for extended periods of time. Pete Conrad, Paul Weitz and Joe Kerwin spent 28 days in orbit as the first crew of Skylab. The second crew - Alan Bean, Jack Lousma and Owen Garriott - spent 59 days in space. The final Skylab crew spent 84 days in space and consisted of Jerry Carr, Bill Pogue and Edward Gibson. Each Skylab crew set new spaceflight duration records. The record set by the final crew was not broken by an American astronaut until the Shuttle-Mir program more than 20 years later. Skylab served as the greatest solar observatory of its time, a microgravity lab, a medical lab, an Earth-observing facility, and, most importantly, a home away from home for its residents. The program also led to new technologies. Special showers, toilets, sleeping bags, exercise equipment and kitchen facilities were designed to function in microgravity. As successful as the program was, the first two crews had to overcome some unexpected challenges. During the station's launch, airflow caused a meteoroid shield to come off, tearing off one of two solar panels and preventing the other from deploying. The damage resulted in reduced power for the station. When the first crew arrived 11 days later, their first task was to repair the damage. Once repairs were complete, full power was restored.

A close-up view of the partially deployed, damaged solar array.

A close-up view of the partially deployed, damaged solar array. A thruster leak caused trouble for the second crew, causing Bean's rendezvous with the station to be more challenging than expected. Once they were on board, a second thruster developed a leak. Plans were drawn up for a rescue, but the crew was able to complete the mission as planned. Original plans called for the station to remain in space after the final Skylab mission, for another 8 to 10 years, possibly to be visited by the Shuttle fleet. But unexpectedly high solar activity foiled the plan, and on July 11, 1979, Skylab re-entered the Earth's atmosphere and disintegrated, dispersing debris across a sparsely populated section of western Australia and the southeastern Indian Ocean. "There was a certain small amount of sadness when we left, realizing we were going to be the last crew to inhabit the spacecraft," Carr said. "It had hung together beautifully for us, and we kind of hated to leave it. But, of course, we were also looking forward to going home."

+ Read More On Nov. 10, 2003, Skylab astronauts Alan Bean and Bill Pogue speak to ISS residents Michael Foale and Alexander Kaleri.

+View this Video

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and Kennedy Space Center

Image above: A view of the Skylab Orbital Workshop in Earth orbit as photographed from Skylab 4 on its return home. Image credit: NASA America's first experimental space station, Skylab, was designed for long durations. Skylab program objectives were twofold: To prove that humans could live and work in space for extended periods, and to expand our knowledge of solar astronomy well beyond Earth-based observations. The program was successful in all respects despite early mechanical difficulties. Skylab was launched into Earth orbit by a Saturn V rocket on May 14, 1973. Through the use of a "dry" third stage of the Saturn V rocket, the station was completely outfitted as a workshop area before launch. Crews visited Skylab and returned to Earth in Apollo spacecraft. Three, three-man crews occupied the Skylab workshop for a total of 171 days and 13 hours. It was the site of nearly 300 scientific and technical experiments, including medical experiments on humans' adaptability to zero gravity, solar experiments and detailed Earth resources experiments. The empty Skylab spacecraft returned to Earth on July 11, 1979, scattering debris over the Indian Ocean and the sparsely settled region of Western Australia.

Image above: A view of the Skylab Orbital Workshop in Earth orbit as photographed from Skylab 4 on its return home. Image credit: NASA America's first experimental space station, Skylab, was designed for long durations. Skylab program objectives were twofold: To prove that humans could live and work in space for extended periods, and to expand our knowledge of solar astronomy well beyond Earth-based observations. The program was successful in all respects despite early mechanical difficulties. Skylab was launched into Earth orbit by a Saturn V rocket on May 14, 1973. Through the use of a "dry" third stage of the Saturn V rocket, the station was completely outfitted as a workshop area before launch. Crews visited Skylab and returned to Earth in Apollo spacecraft. Three, three-man crews occupied the Skylab workshop for a total of 171 days and 13 hours. It was the site of nearly 300 scientific and technical experiments, including medical experiments on humans' adaptability to zero gravity, solar experiments and detailed Earth resources experiments. The empty Skylab spacecraft returned to Earth on July 11, 1979, scattering debris over the Indian Ocean and the sparsely settled region of Western Australia.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I had to change the comment format on this blog due to spammers, I will open it back up again in a bit.