The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was apocalyptically awful. 70 years ago today, an estimated 90,000 people were immediately killed when Little Boy detonated 1,950ft above Hiroshima – 50,000 more would die by the end of the year. Two days later, Nagasaki was struck by ‘Fat Man’, killing approximately 80,000 people. It was, as the Allies threatened during the Potsdam Conference, ‘prompt and utter destruction’.

Just four months into his presidency, President Harry Truman was tasked with making one of the most important decisions in human history. He chose to put an atomic full stop on six long years of unprecedentedly bloody conflict – here are five reasons why he made the right decision.

1. Imperial Japan was fanatical and barbarous in the absolute extreme.

Imperial Japan was a militaristic and dictatorial theocracy whose generals had fatal contempt for their enemies and a total disregard for Japanese lives. At the root of the country’s fanaticism was Emperor Hirohito, the celestial figurehead whom the zealous masses were expected to worship and even die for. The true rulers of Japan, however, were the belligerent top brass of the military.

With a desire for natural resources and their own lebensraum, the Japanese colonized Manchuria, northeast China in 1931. In 1937, Chinese resistance led to the Second Sino-Japanese war, beginning a campaign of innumerable Japanese atrocities.

The most infamous of these atrocities occurred in China’s then-capital Nanking on 13 December 1937. In an appalling act of genocide, the Japanese murdered up to 300,000 people and raped tens of thousands of women over a six-week period.

There are dozens of eyewitness accounts and photographs that reveal the sickening details of the massacre. Two survivors reported that thousands of children, women and the elderly were bound with wire or rope, driven into four columns and then mown down with ‘about twenty’ machine guns. Once the bodies had ‘heaped like mountains’, the murderers then bayoneted the corpses en masse, eventually dousing the pile with kerosene and setting it ablaze. No one was safe from Japanese bayonets, not even infants, some of whom were brutally skewered like kebabs.

The suffering endured by Nanking’s women will leave many readers incredulous. One Chinese cook gave his account of seeing dozens of female corpses, the majority of which had ‘their abdomens cut open and their intestines squeezed out.’ Some of the women had been pregnant, lying ‘dead together with their fetuses covered with blood’, their breasts having been ‘either cut off or bayoneted into a mixture of flesh and blood.’

1300 miles to the northeast of Nanking was the ‘Epidemic Prevention and Water Purification Department of the Kwantung Army’, better known as Unit 731.

This ghastly facility was host to a range of lethal human experiments, including thousands of vivisections without anesthesia. Prior to the surgeons ruthlessly opening their victims up, they had infected them with various diseases, which ranged from the bubonic plague and anthrax to syphilis and cholera. As part of research into gangrene, some victims had limbs frozen and then thawed, all the while being conscious, of course.

Many experiments were entirely military minded. Victims would be restrained and exposed to the effects of grenades, flamethrowers and various chemical weapons, the latter of which they were readily using in combat against the Chinese.

In a similar manner to the Americans’ immoral Operation Ranch Hand programme during the Vietnam War, low-altitude Japanese planes spread plague-infested fleas over the cities of Ningbo and Changde, killing thousands of people.

This disagreeable form of warfare flouted the Geneva protocol, which officially prohibited the use of ‘asphyxiating, poisonous or other gases, and of bacteriological methods of warfare’ on 8 February 1928.

There is far too little space here to fully elaborate on the crimes of Imperial Japan, which can be reasonably deemed one of the most disgustingly immoral forces the world has ever seen. The bombs stopped them from perpetrating any further barbarity – some may say it was vindication.

2. Imperial Japan was utterly averse to surrender and had a fatal contempt for those who weren’t.

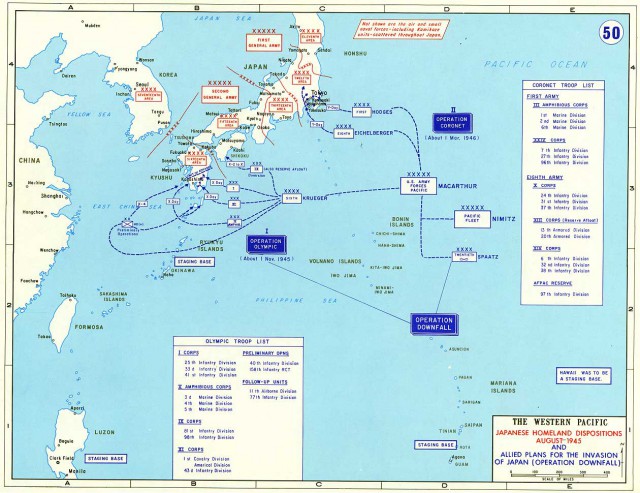

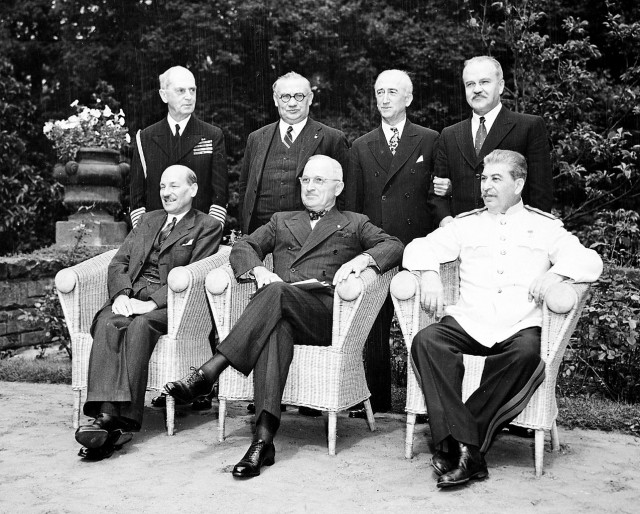

The Potsdam Conference 1945

Despite devastating losses – such as their air power being reduced from 430 planes to around 100 during the day-long ‘Great Marianas Turkey Shoot’ – the centuries-old Japanese ethos was that suicide, particularly suicide that killed others, was infinitely nobler than waving the white flag.

Staggeringly low surrender statistics were common throughout the Pacific Theatre. During the bloody Battle of Tarawa, only 17 of 3000 Japanese troops surrendered. At Saipan, the vast majority of the 30,000 strong garrison died. 22,000 civilians also died in Saipan, which was over two thirds of the population.

Japanese contempt for surrender caused them to subject Allied POWs to appalling cruelty. The stories of the Burma railway’s hellish protracted brutality are well known – 16,000 POWs and an incalculable number of Burmese and Malay workers died, chiefly from a range of terrible diseases.

There are many lesser-known stories of the shocking games the Japanese used to play with POWs, too. As mentioned earlier, the Japanese had a penchant for bayoneting people. Robert O’Brien, a New York sailor aboard the USS Penguin, experienced their predilection first hand.

After Guam fell on 10 December 1941, O’Brien and his comrades were forced to run through a gauntlet of Japanese soldiers, who hacked, slashed and hit them with bayonets and rifle butts. O’Brien survived this sick game but death surrounded him, including the man directly behind him. Several men’s scalps had been gored; one man bled to death from a deep cut along his back. Another man was shot through both ankles, falling to the ground and having his wounds maliciously stomped on by the Japanese.

Three years later, on October 25 1944, the Japanese would employ their most infamously desperate line of defense – the kamikaze pilots. Of the 3860 kamikaze pilots who died, only 19% hit their targets. Their futile deaths become emblematic of Japanese fanatical resistance.

The most costly instance, however, of Japan’s obstinate refusal to surrender was the Japanese Premier’s use of mokusatsu. Meaning ‘take no notice of’ or ‘treat with silent contempt’, mokusatsu was Kantaro Suzuki’s response to the United States’ demand for unconditional surrender at the Potsdam Conference. The Potsdam Declaration stated that if the Allies’ terms were not met, Japan would face ‘prompt and utter destruction’.

The translation’s accuracy is a point of contention, as mokusatsu doesn’t always mean ‘treat with silent contempt’. However, Suzuki was in no position to mull over the proposition, to bargain with his enemies and save face. His country had raped, pillaged and caused the death of millions of people. He was threatened with ‘prompt and utter destruction’, yet his laconic response to this damningly sincere threat suggests he didn’t take the declaration seriously and perhaps considered the far costlier invasion of the mainland to be preferable.

Surrender wasn’t achieved even after Hiroshima was devastated. It was only following Fat Man’s 21-kiloton detonation over Nagasaki that the Japanese finally capitulated.

Even in these desperate times, Emperor Hirohito tried his utmost to save face for himself and his battered nation. On 15 August 1945, Hirohito addressed his people for the first time during his leadership, asking them to ‘endure the unendurable and bear the unbearable’ and, in what may truly be the understatement of the 20th century, stated that the war had turned ‘not necessarily in Japan’s favour’. Without the sudden atomic step-up, the Americans would most probably have been forced to execute Operation Downfall.

3. Operation Downfall, the proposed invasion of Japan, would have resulted in more casualties on both sides.

Comprising Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyushu (southern island), and Operation Coronet, the invasion of the Honshu (main island), Operation Downfall was a very daunting prospect.

It would have been a campaign of terrible violence, punctuated by conflicts such as the Battle of Honshu and the Battle of Kyushu, which could have been another Stalingrad. Japan had defended tiny Pacific islands like Peleliu and Iwo Jima with great ferocity; defense of the Japanese mainland would have quite likely introduced the Allies to wholly new levels of fatal intensity.

It would have made WWII, the most catastrophic war in history, significantly worse. Over a million Allied casualties were estimated, for the Japanese this figure rose massively to the tens of millions.

One can only speculate how the civilians would have behaved. Revolt was always a possibility, but their lack of knowledge regarding Japan’s calamitous defeats in the Pacific and the intense reverence for Hirohito would likely have resulted in widespread loyalty.

Compare the multi-million casualty estimates of Operation Downfall to the atomic bombs’ 250,000 – 300,000 Japanese and approximately 20 Allied POW deaths, and the Manhattan Project almost seems like a humanitarian effort. This significant disparity alone is a strong justification for the bombs’ use.

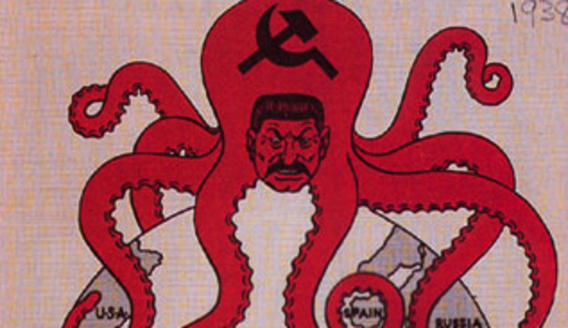

4. It stymied Soviet influence and the creation of another North Korea.

The bombs hastened Japan’s unconditional surrender, allowing the Americans to execute their considerable altruistic efforts on their own terms. Whilst the Marshall Plan was pumping $13 billion ($120 billion today) into Europe, the United States occupied Japan and established the Supreme Command of Allied Powers (SCAP) with the intention of creating a prosperous democracy and key Asian ally.

Led by General Douglas MacArthur, SCAP paved the way towards free market capitalism, promoted women’s rights and banned former military officers from political leadership in the new government. Crucially, MacArthur had the pragmatism to allow Emperor Hirohito to stay, reducing his position to a firmly ceremonial one and waiving his ability to wage war. The consequences of removing such a beloved figure would have likely had a dire effect on Japanese morale, igniting an array of dissidence. When Hirohito died in 1989, Japan had the world’s second largest economy.

Now imagine if the Soviet Union’s involvement in Japan’s future was more than a meager ‘advisory role’, imagine if they had the same clout as they did in Korea. Russia had invaded Japanese Manchuria on 9 August 1945, swiftly defeating their opposition and moving south, eventually reaching the Korean peninsula. As agreed at Potsdam, the Soviets began their occupation of North Korea and, on 8 September, the United States occupied South Korea, the partition line being along the 38th parallel.

On 24 July 1948, US-backed Syngman Rhee became the first President of South Korea. Although his leadership was marred by authoritarianism, Rhee’s moral ambiguities were dwarfed by the Soviet Union’s leader of choice – the wretched Kim Il-Sung. North Korea has been under the rule of the Kim Dynasty ever since, suffering all manner of human underdevelopment such as poverty, international isolation, awful infrastructure, one of the world’s worst human rights records and a famine that resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Instead of the rich, pacifist nation that we know today, strong Soviet influence could have carved Japan up, perhaps rendering Sapporo a Stalinist, retrograde circus of oppression much like Pyongyang. We could have seen another East Germany, or perhaps even another Cuban missile crisis. One can only speculate, but it is demonstrable that America’s devastating yet presciently decisive action helped establish Japan as the first ‘Tiger economy’, influencing economic reforms in South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan, all of which are beacons of prosperity and development in Asia.

5. The destructive precedent it set wasn’t quite as epochal as many believe – conventional fire-bombings were similarly devastating.

Indeed, America’s utilization of atomic weaponry irrevocably changed warfare. Scores of people were seared beyond recognition, their shadow sometimes scorched onto the surrounding surfaces. Some simply vanished. For many, death was a more protracted affair, their bodies bleeding, oozing and generally falling apart as their DNA was mutilated by radiation poisoning, also known as acute radiation syndrome (ARS).

Despite all of this, one must not forget the diabolical effectiveness of the Allies’ conventional weaponry. Low-altitude incendiary bombing killed many more people than Little Boy and Fat Man. The lowest estimate is 241,000 – which already meets the estimated death toll of the atomic bombs – and the highest is an enormous 900,000.

The zenith of this ghastly destruction was the Operation Meetinghouse raid above Tokyo on 9 March 1945. 2000 tons of incendiaries were dropped on the city, destroying 16 square miles and killing around 100,000 people. Epic fires consumed the city, creating a blood-red mist of such putrid fragrance that the pilots had to wear oxygen masks to avoid vomiting. A US survey found that the 300 B-29 Superfortresses killed more people during the raid than at any single moment in history – an astonishing conclusion, indeed.

The masses that burned in Japan’s ‘paper cities’ have been barged out of the public consciousness by Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which were ultimately a mere extension of the Allies’ similarly devastating conventional-bombing campaign.

Written by Jack Hawkins for War History Online

No comments:

Post a Comment

I had to change the comment format on this blog due to spammers, I will open it back up again in a bit.