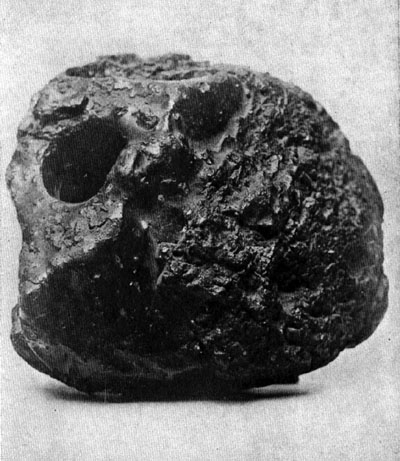

An Example of a Coal Torpedo Captured by the Union after the fall of Richmond.

Throughout the entirety of the American Civil War, the Confederate Navy was hopelessly outmatched by the Union Navy. Union warships enacted a blockade of the Confederate coast that placed a stranglehold on Confederate trade. Though they attempted to counter the might of the Union Navy through production of advanced warships, they could not overcome the sheer numbers of Union warships. Thus, they turned to a more indirect method of attacking Union shipping. This secret weapon of the confederacy was the coal torpedo.

Courtenay wrote Confederate President Jefferson Davis in November of 1863 to explain his plan. Davis, realizing the potential of the device, agreed to the project. Davis ordered his Secretary of War to arrange for immediate production of coal shells. Production would be carried out by the 7th Avenue Artillery shop in Richmond, Virginia.

Manufacturing these bombs turned out to be surprisingly easy, no different than that of explosive shells. A piece of real coal was used to create a mold. This mold would then be used to create a realistic looking casing for the bomb. Once explosives were placed inside the casing, the bomb was coated with coal dust to further add to the disguise.

Though Courtenay continued to call his invention the Coal shell, the were more commonly known by the name coal torpedo. At this point in history, the phrase torpedo referred to a wide range of explosive devices, nothing like the torpedo we are familiar with today.

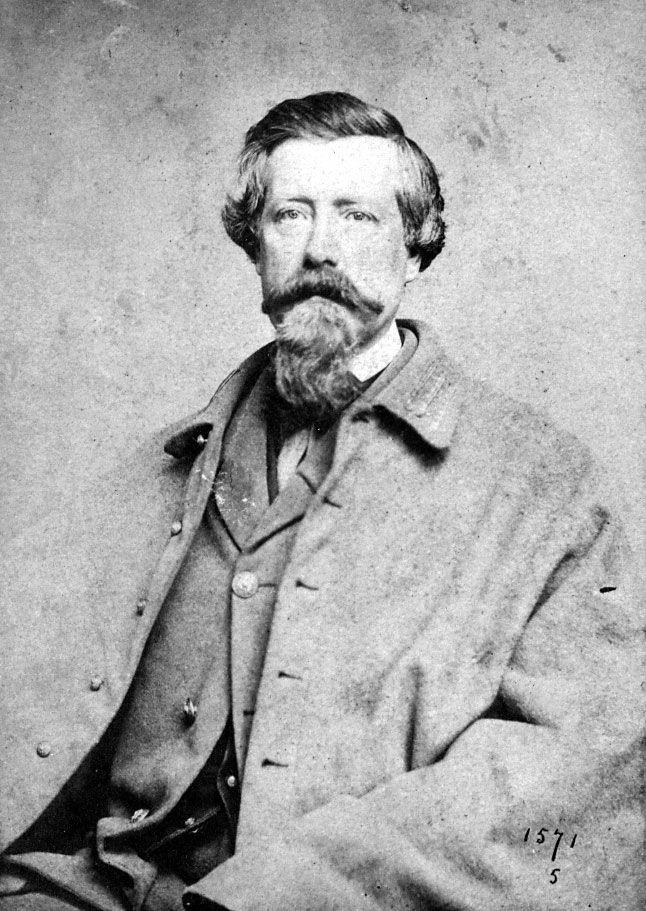

Courtenay was hoping that his new invention would allow him a chance to collect a bounty on Union shipping that the Confederate government was offering. However, as a civilian he was illegible. In response, the Confederate Government, formed a new secret service corps of which Courtenay was given command.

This secret service corps would not remain secret for long. Only one month later, a courier was captured by the crew of a Union Gunboat. As luck would have it, he was carrying a letter from Courtenay that gave an in-depth description of the coal torpedo. This information was quickly sent to Admiral David Porter. Porter reacted quickly, making sure every vessel knew of this new weapon. In a order to his men, he wrote that,

“The enemy have adopted new inventions to destroy human life and vessels in the shape of torpedoes, and an article resembling coal, which is to be placed in our coal piles for the purpose of blowing the vessels up, or injuring them. Officers will have to be careful in overlooking coal barges. Guards will be placed over them at all times, and anyone found attempting to place any of these things amongst the coal will be shot on the spot.”

To make matters worse, the Union Navy knew full well who was behind the coal torpedo. Seeking refuge, Courtenay convinced President Jefferson Davis to allow him to travel to England. Safe from Union soldiers, Courtenay could continue to direct his secret service corps from across the Atlantic Ocean without fearing the consequences of his capture.

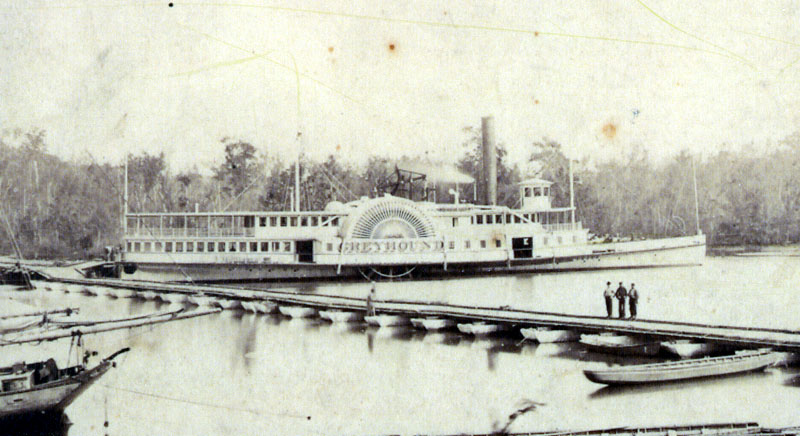

Despite the difficulties in directing a campaign from across the Atlantic Ocean as well as the Union forces being aware of his weapon, Courtenay achieved some success with the coal torpedo. The steamer Greyhound is believed to be one of the victims of the coal torpedo.

In November 1864, the crew of the Union steamer Greyhound, headquarters of General Benjamin Butler, caught some suspicious people aboard the vessel. After evicting them from the ship, the Greyhound traveled down the James river. On November 27, the ship was destroyed by a boiler explosion, forcing the crew to abandon ship. Admiral David Porter believed it to be the work of the coal torpedo.

Earlier that year, the steamer USS Chenango also suffered a boiler explosion while sailing south along the East Coast. Though she did not sink, she was out of commission for a year.

Other uses of the coal torpedo is harder to find. Prior to the fall of Richmond, all documents on the use of the weapon was burned. However, during the last year of the Civil War, a noticeable increase in boiler explosions occurred. Many were due to mysterious or uncertain circumstances. It is safe to say that the coal torpedo is a likely suspect for a few of these explosions.

During this time however, the steamboat Sultana was destroyed after three of her four boilers exploded on April 27, 1865. At the time she was carrying over a thousand former prisoners of war back home from Confederate prison camps. 1,192 people were killed, making it one of the deadliest maritime disasters in United States history. Years later, Confederate saboteur Robert Louden claimed to have planted a coal torpedo aboard the Sultana. However, this claim remains controversial and the official explanation remains that the boilers exploded due to improper water levels inside the boil

Though Courtenay was unable to profit from the coal torpedo. It reappeared several times throughout history. During World War II, both the Axis and the Allies attempted to use coal torpedoes to sabotage the other. Years later, during the Vietnam war, CIA operatives made plans to utilize coal torpedoes to sabotage North Vietnamese locomotives. The coal torpedo did not change the tide of the Civil War, but Courtenay’s innovative weapon lived on.

Wasn't something like that tried in WWII by the SOE or OSS?

ReplyDeleteHey Bob;

ReplyDeleteI think something like this was tried by the SOE during WWII, but I am not certain.