Everyone knows the name “Mauser” and the bolt action rifles

associated with it. Here are 10 facts you may not have known were

associated with the Mauser story:

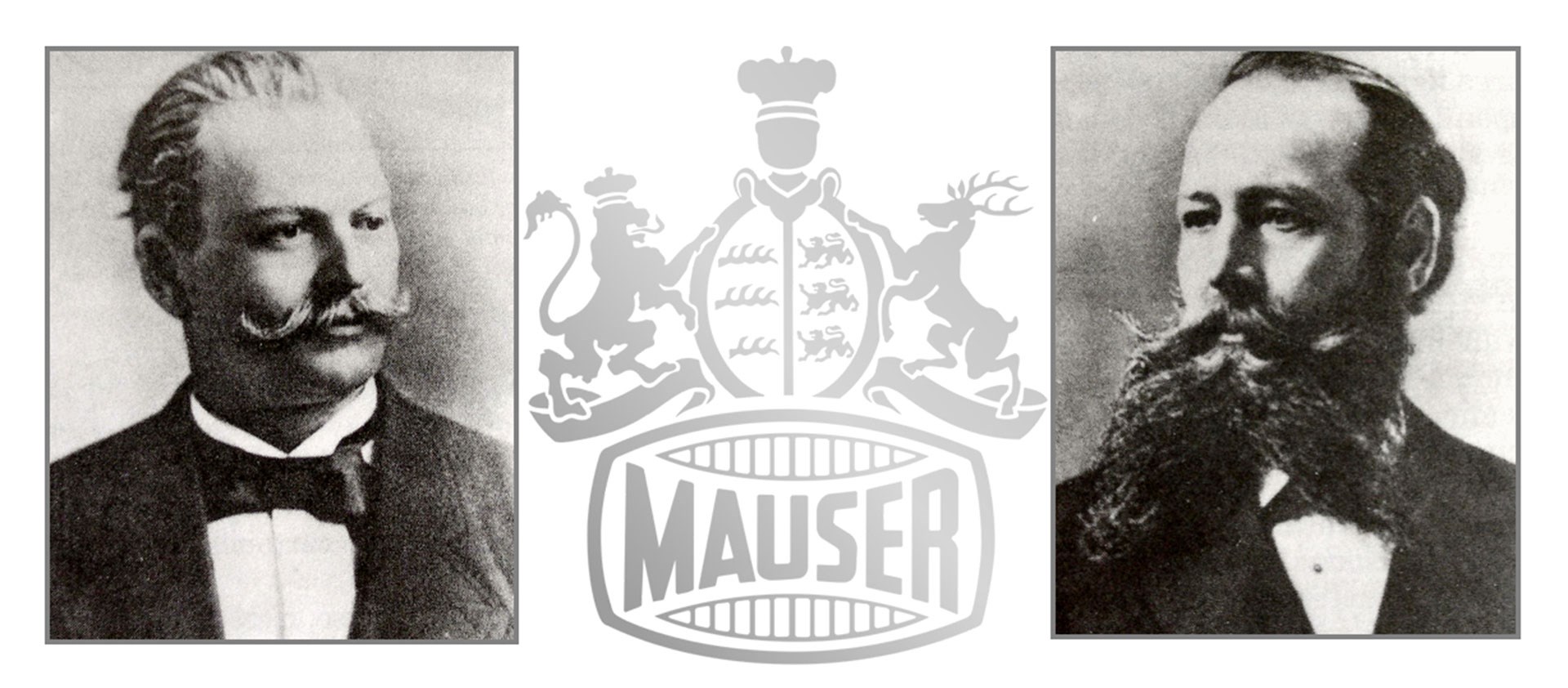

One: There Were Two Mausers - Paul And Wilhelm

Brothers Wilhelm Mauser (right) and Paul Mauser (left).

Brothers Wilhelm Mauser (right) and Paul Mauser (left).

The Mauser firm was the work of brothers Peter Paul (known simply as

“Paul” ) and Wilhelm Mauser. Following military service, the Mauser

brothers’ father Franz became a gunsmith at the royal armory at

Oberndorf, a small town on the Neckar River in Germany. The younger

brother Paul would develop an interest in artillery through his own

military service, which eventually led to small arms design. Wilhelm

served as business manager for the company.

Wilhelm died in 1882 at the age of 47. Paul remained the technical

director of the company through its major developments and would live to

the age of 76 in 1914.

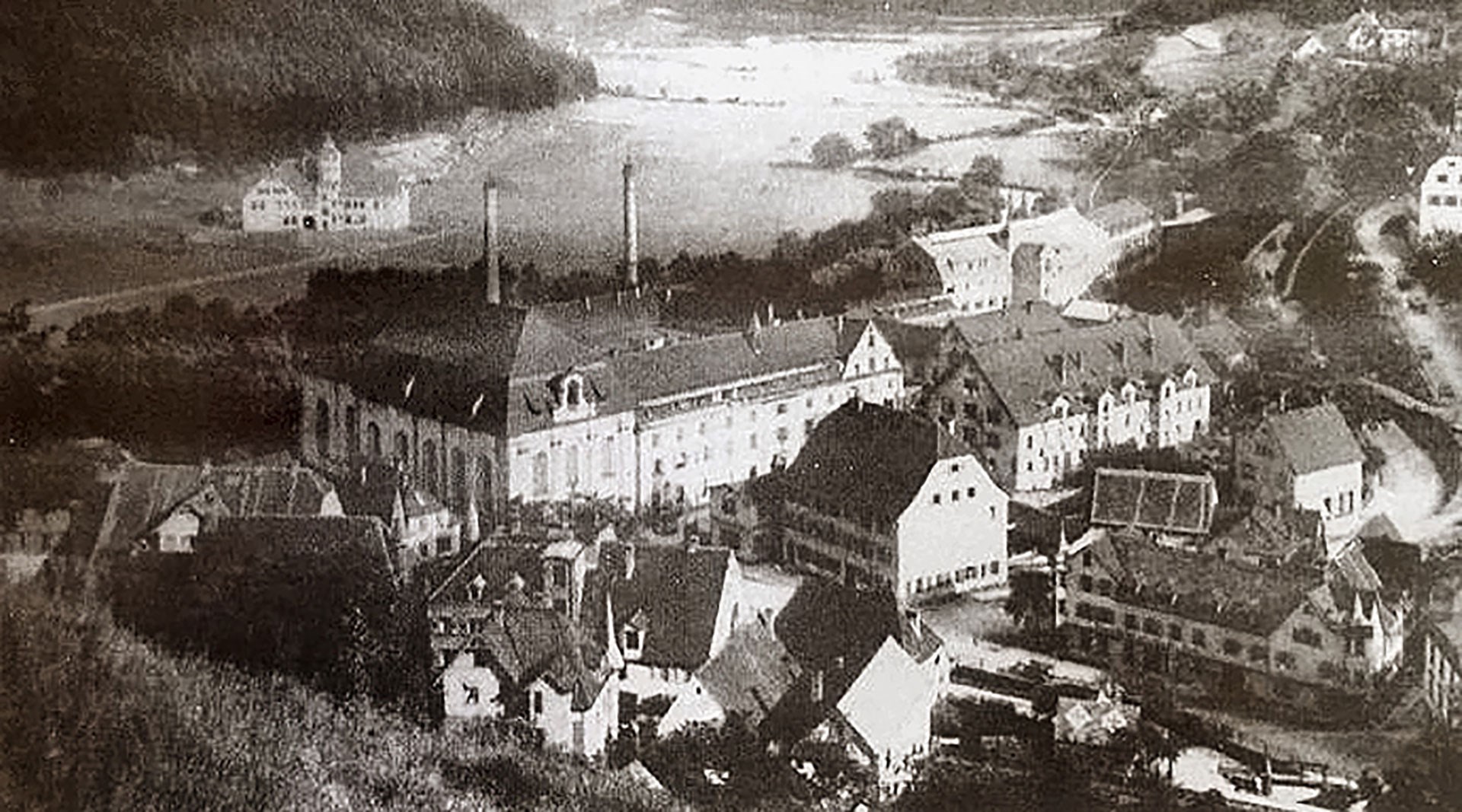

The Mauser factory in Oberndorf am Neckar in 1910.

The Mauser factory in Oberndorf am Neckar in 1910.

While many of Mauser’s innovations were patented in the name of Paul

Mauser, throughout the article that follows, when we say “Mauser” we’re

referring to the company, in general.

Two: Mauser Didn’t Invent The Bolt Action

While Mauser is responsible for many of the design elements that we

see in modern turn-bolt actions, they did not invent the system. The

first firearm to use a rotating bolt to open and close the breech was

the Dreyse Needle Gun,

which used a paper-cased black powder cartridge that was internally

primed so that a needle-like firing pin had to pierce the case to reach

it. Developed in the 1820s by Johann Nicolaus von Dreyse, the design was

perfected in 1836 and adopted by the Prussians in 1841. Dreyse’s system

gave a massive rate-of-fire advantage over contemporary muzzleloading

muskets.

A Model 1860 Dreyse Needle Gun with its bolt handle visible.

A Model 1860 Dreyse Needle Gun with its bolt handle visible.

As modern, breechloading firearms were developed, several would use

the Needle Gun’s turn-bolt system. Two bolt-action firearms, the Palmer

and the Greene (the first bolt action used by the U.S. military), were

issued during the Civil War.

The Greene breechloading bolt-action rifle from the Civil War era.

The Greene breechloading bolt-action rifle from the Civil War era.

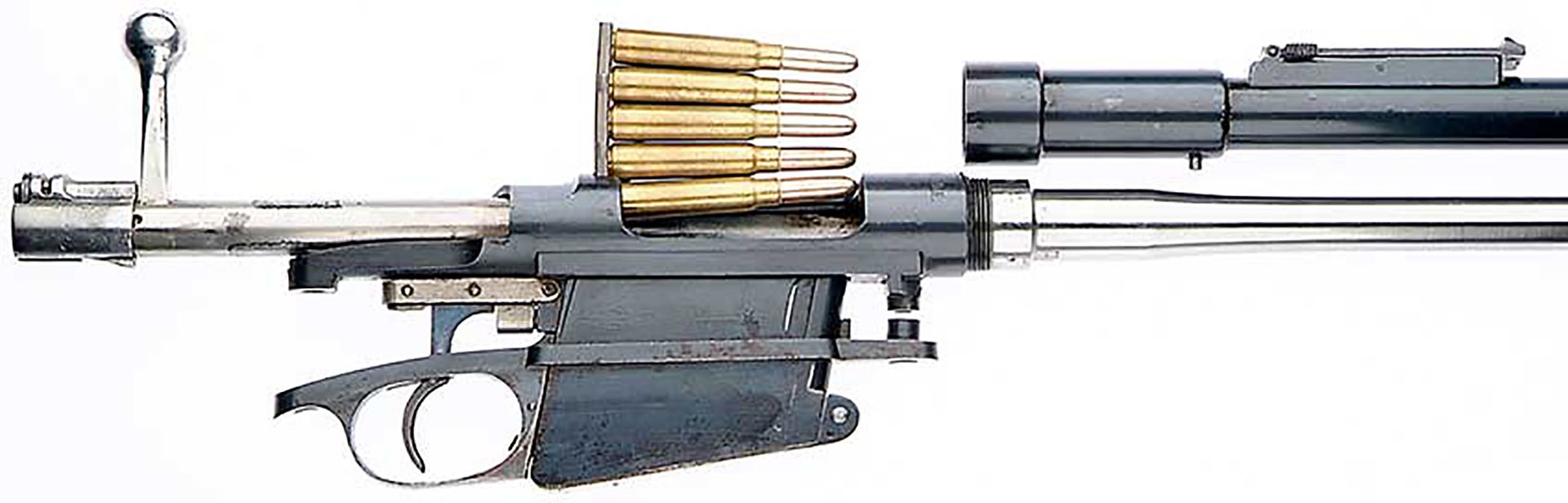

The action of the Greene, showing its turning bolt mechanism and locking lugs.

The action of the Greene, showing its turning bolt mechanism and locking lugs.

Mauser’s earliest design was an improvement of the Needle Gun that

could be used as a way to convert muzzleloading muskets to breechloaders

using a turn-bolt system, a mechanism that the company would eventually

become synonymous with.

Three: Mauser Had An Early Connection To America

The Mauser brothers came from a large family and an older brother,

Franz, went to the U.S. and would eventually work for the Remington arms

company.

Samuel Norris, who was Remington’s agent in Europe, would be

influential in the infant Mauser company. Norris was impressed with

Mauser’s early design and became convinced it could be used to convert

needle guns, like the French Chassepot,

to fire metallic cartridges. Norris partnered with Mauser and provided

financial backing, moving the Mauser brothers to Liege, Belgium.

The action of the Interim Model 1869/70, a prototype that would lead to the first successful Mauser, the M1871.

The action of the Interim Model 1869/70, a prototype that would lead to the first successful Mauser, the M1871.

The partnership crumbled when it failed to interest any governments

and the Mauser brothers returned to Oberndorf where they continued to

develop a design that would eventually become their first successful

firearm, the 1871 Mauser.

Mauser’s first successful model, the 1871, was a single-shot that fired a blackpowder cartridge.

Mauser’s first successful model, the 1871, was a single-shot that fired a blackpowder cartridge.

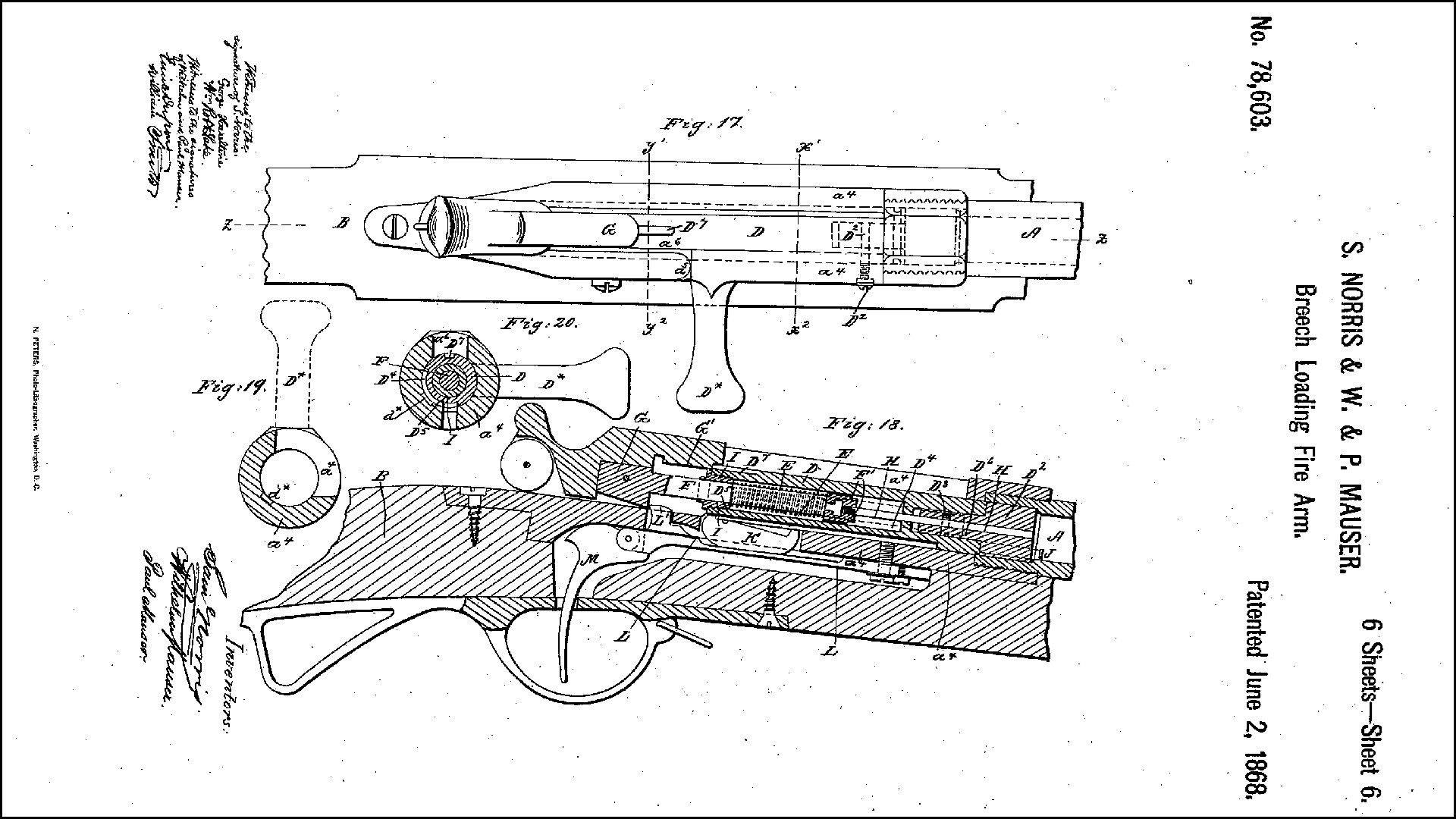

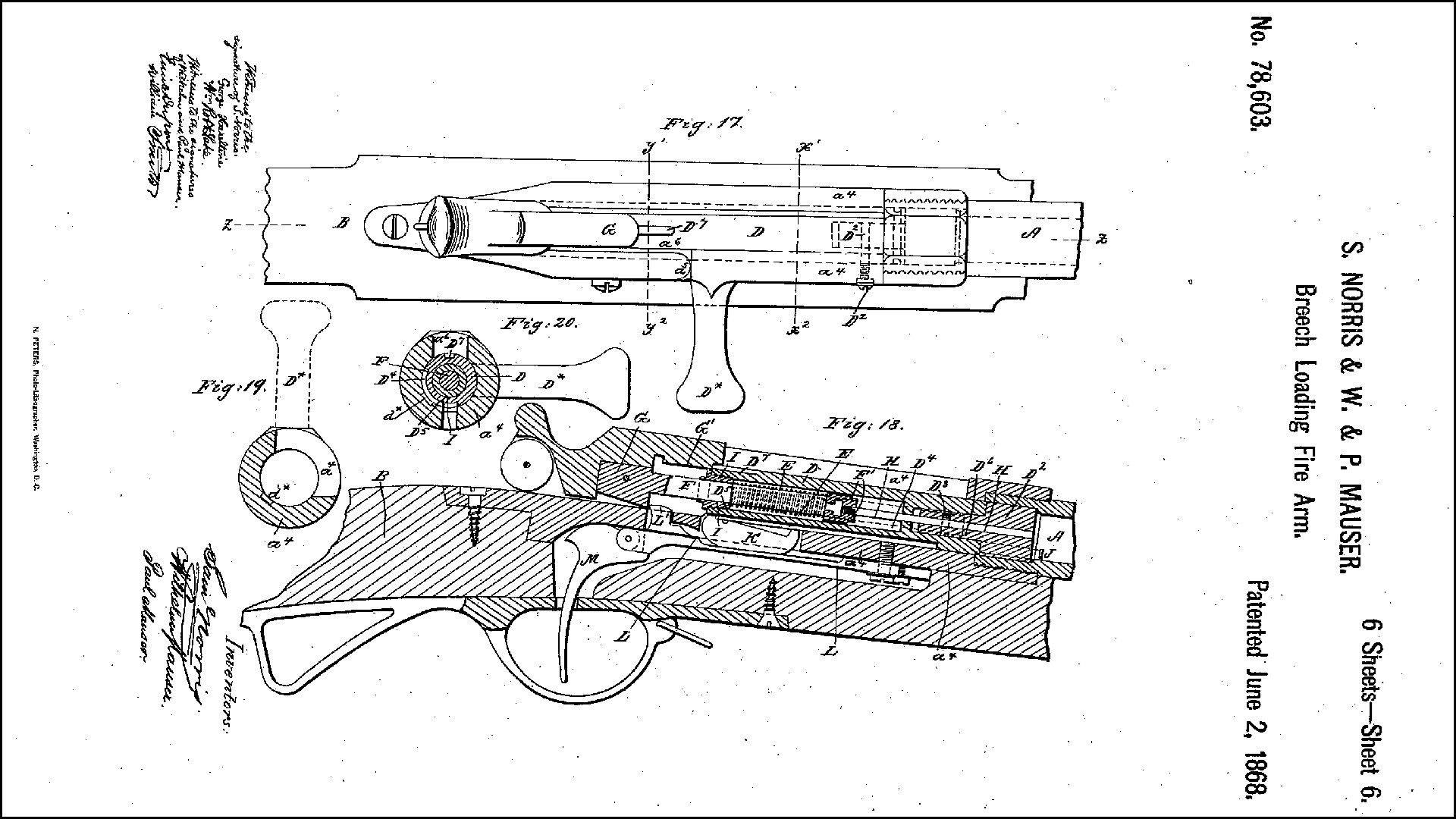

Four: Mauser Took Out An Early Patent Of Its Designs In The U.S.

As a result of the partnership with Norris, Mauser would apply for

its first patent in the United States. Granted on June 2, 1868, Patent

No. 78,603 for “Improvements in Breech Loading Firearms” was taken out

in the name of “S. Norris & W. & P. Mauser.” The patent would

cover features like the rifle’s cock-on-opening bolt system and the

interface between the sear and firing pin.

Mauser’s first U.S. patent for “Improvements in Breech Loading Firearms.”

Mauser’s first U.S. patent for “Improvements in Breech Loading Firearms.”

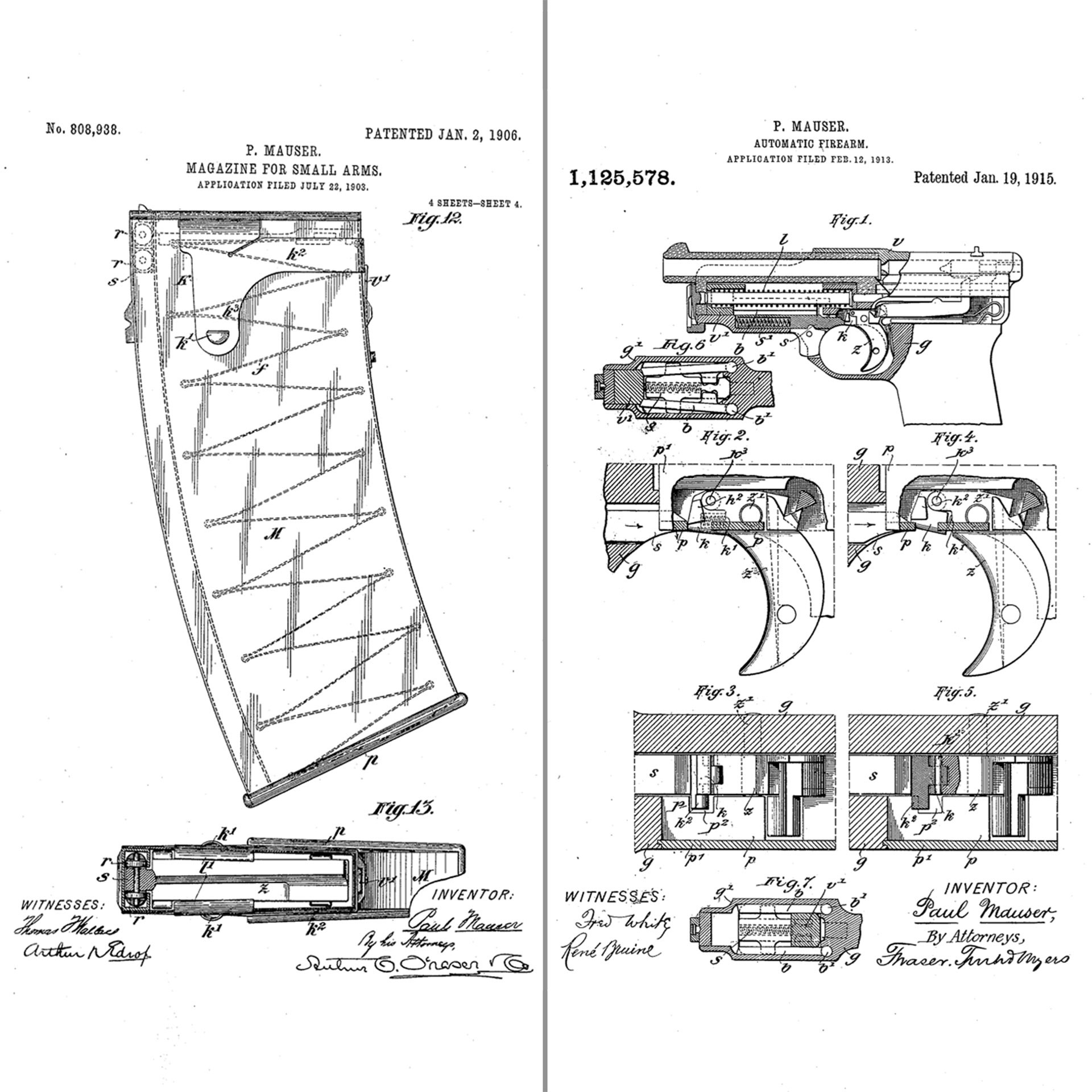

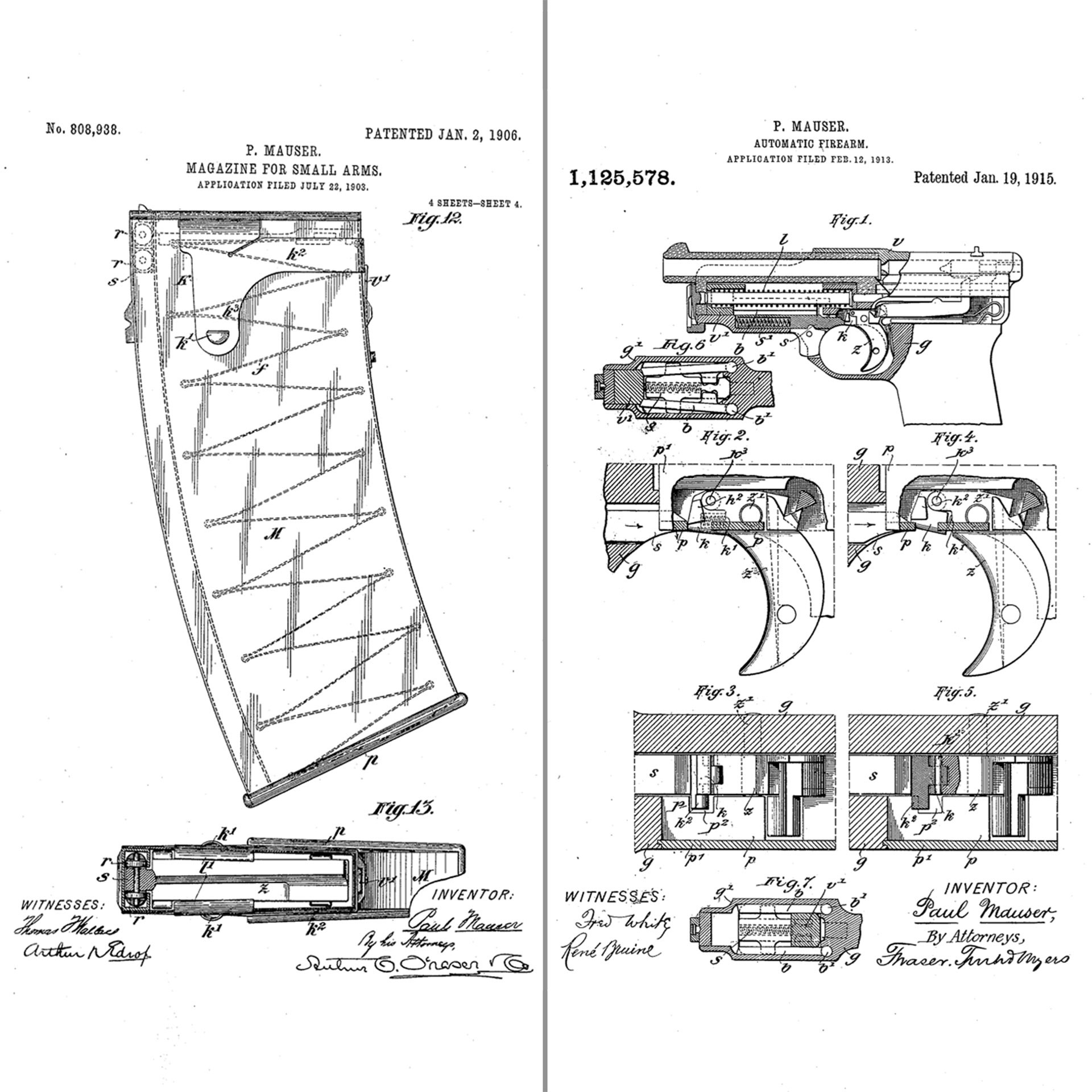

It was the first of many patents that Mauser would take out in the U.S., covering everything from ammunition to scope mounting.

A 1915 Mauser patent for semi-automatic pistol design (right) and a 1906 Mauser patent for a rifle magazine (left).

A 1915 Mauser patent for semi-automatic pistol design (right) and a 1906 Mauser patent for a rifle magazine (left).

The patent model for the Mauser-Norris rifle is in the collection of

the Smithsonian Institute, but not currently on public display. Another

Mauser-Norris prototype is in the collection of the National Firearms Museum at the NRA headquarters, as are many of the firearms whose images appear in this article.

An early Mauser-Norris prototype, showing the action opened.

An early Mauser-Norris prototype, showing the action opened.

Five: The 1888 Commission Rifle Is NOT A Mauser (But It’s Important To Mauser History Anyway)

A Model 1888 Commission rifle made at the Amberg arsenal.

A Model 1888 Commission rifle made at the Amberg arsenal.

While the German 1888 Commission rifle is often referred to as a

“Mauser,” it’s not. As the name implies, in response to the French

adopting the revolutionary 1886 Lebel

with its modern, high-velocity smokeless cartridge, the Germans formed a

military commission to develop a new rifle to replace the black powder

cartridge-firing Mauser 71/84.

The result was a design that combined innovations of both Paul Mauser

and Ferdinand Mannlicher. The rifles used a Mauser-type firing mechanism

and safety combined with a Mannlicher magazine that utilized an en-bloc

clip. The rifle also introduced the 8 mm cartridge that would

eventually become the 7.92x57 mm or “8 mm Mauser” that would be the

German service cartridge through the end of World War II.

While the 1888 Commission Rifle was a successful design that

soldiered on through World War I, it was quickly outclassed in the

rapidly changing world of late 19th-century infantry rifles. Mauser

immediately began developing what would become their own groundbreaking

design, the Model 1889, that would eventually evolve into the classic

1898 Mauser.

On Mannlicher’s side the ‘88 Commission would lead to the Romanian and Dutch service rifles, Mannlicher-Schoenauer hunting and military rifles and inspire other military rifles, like the Italian Carcano series.

A

Model 1888 Commission rifle action (top) compared to a 1903/14 Greek

Mannlicher (center) and a 1903 Mannlicher Schoenauer sporting rifle

(bottom).

A

Model 1888 Commission rifle action (top) compared to a 1903/14 Greek

Mannlicher (center) and a 1903 Mannlicher Schoenauer sporting rifle

(bottom).

Six: The First Mauser Handgun Was Not A Semi-Automatic…Or A Revolver

A Mauser Model 1896 “Broomhandle” semi-automatic pistol.

A Mauser Model 1896 “Broomhandle” semi-automatic pistol.

While it may be the best known handgun associated with the Mauser name, the semi-automatic C96 “Broomhandle” pistol was not Mauser’s first handgun design.

In 1878, Mauser developed a revolver for an upcoming German military

handgun trial. The M78 was a single-action revolver, the first

generation of which had a solid frame with a separate ejector rod, as

was common in European revolvers of the time. The second generation M78

had a break-open action with a hinge at the top of the frame that was

made in both single-action and double-action forms.

The M78 got its “Zig-Zag” nickname from its method of cylinder

rotation. A lug attached to the hammer mechanism engaged the angled

grooves on the cylinder to rotate and lock it when the hammer was cocked

or the trigger was pulled.

The Mauser Model 1878 “Zig-Zag” revolver.

The Mauser Model 1878 “Zig-Zag” revolver.

While the winner of the trials was the 1879 Reichsrevolver, the Zig-Zag would continue in production in various calibers for the civilian market until the Broomhandle was introduced.

But the Zig-Zag was also not the first Mauser handgun. In 1877,

Mauser designed a single-shot pistol that used a falling block

mechanism. A thumb-actuated latch dropped the breech, ejecting the spent

case and allowing for another cartridge to be loaded. Pulling the

trigger cocked and fired an internal striker. As a single-shot handgun

was outdated by the late 1870s (though other European manufacturers were

still designing and building them at the same time as Mauser), only

about 100 of these C77 pistols were produced before Mauser moved on to a

revolver design and ultimately, semi-automatic handguns.

A Mauser C77 single-shot pistol with the action closed (right) and opened for loading (left).

A Mauser C77 single-shot pistol with the action closed (right) and opened for loading (left).

Seven: Mauser Perfected The Clip-Loading System

While we all know that a “clip” is different than a “magazine,” Mauser was responsible for innovations in both areas.

In the late 19th century, there were several competing magazine

designs for military rifles. Some, like Mauser’s own 71/84, used a

tubular magazine under the barrel, James Paris Lee had invented a

detachable (for cleaning) box magazine and Ferdinand Mannlicher had

developed a system where a clip of cartridges was inserted into a fixed

box magazine and stayed there as the cartridges were expended.

The main advantage of the Mannlicher design was how rapidly a full

clip of cartridges could be loaded. But the Mannlicher system also had

its disadvantages. Without the clip, the rifle wouldn’t function, and

the Mannlicher design couldn’t be “topped up” after a few cartridges had

been fired (problems familiar to anyone who has used the en-bloc clip

of the M1 Garand). Finally, the bottom of a Mannlicher magazine had to

be open to allow the empty clip to fall from the rifle after the last

round was fired, allowing for dirt and dust to enter the rifle’s

mechanism.

Though they were not involved with the design of the ‘88 Commission

rifle, Mauser quickly responded to it with a modern, smokeless

cartridge-firing rifle of their own. They developed a rifle for a

Belgian trial that would define many of the features of turn bolt

firearms that carry on to this day. What would eventually become the Belgian Model 1889 Mauser

was a major break from Mauser’s earlier designs. Among its features was

a built-in, single-column box magazine that extended below the action

in front of the trigger guard.

Mauser sought to retain the advantages of the speed of the Mannlicher

clip loading system and eliminate its drawbacks. To this end, the

company designed a flat metal clip that held the cartridges by their

rims. The clip was inserted into a groove on the receiver bridge, and

then the cartridges were “stripped” from the clip into the magazine with

the thumb. Pushing the bolt forward to load the first cartridge ejected

the clip from the action. The feed lips were built into the magazine

box, so single cartridges could be loaded at any time during the firing

process.

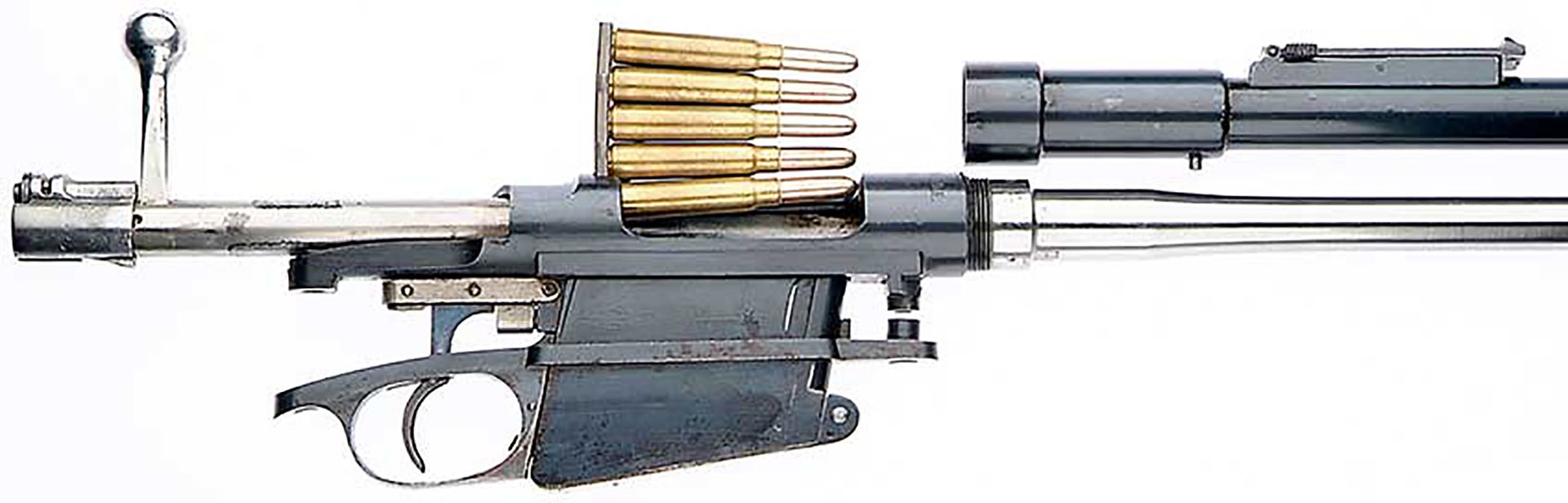

A

Belgian Model 1889 Mauser action with the barrel jacket removed,

showing a stripper clip, or charger, of cartridges inserted into the

action.

A

Belgian Model 1889 Mauser action with the barrel jacket removed,

showing a stripper clip, or charger, of cartridges inserted into the

action.

With the stripper clip loading system came several other innovations

to the Mauser rifle design. The locking lugs were moved to the front of

the bolt, allowing the bolt handle to be moved behind the rear receiver

bridge. This placed the bolt handle closer to the firing hand for

quicker manipulation. It also meant that the rear receiver bridge didn’t

have to be split to allow the bolt handle to pass through, a design

element that would eventually become important for the mounting of

telescopic sights.

The success of designs like the 1889 meant that the “stripper clip”

form of loading and the box magazine would go on to become the dominate

design for all non-Mannlicher military bolt action rifles, from the 1903 Springfield to the Schmidt-Rubin straight pulls.

Eight: Mauser Was Influential In The Creation of FN

When Belgium adopted a Mauser design in 1889, they wanted to produce

their new rifle in-country. In response, a conglomerate of the nation’s

gunmakers formed

Fabrique Nationale d’Armes de Guerre or

as it was more simply known “FN.” In the early days, 50 percent of FN

stock was owned by Ludwig Loewe & Co., a German corporation that

also owned Mauser.

Along with 275,000 Model 1889s, FN would also manufacture other

models of Mauser. When the Versailles Treaty prohibited Mauser from

exporting military weapons, FN became one of the leading producers of

Mauser-type rifles, mainly of the 1898 design.

A Venezuelan contract Model 1924/30 rifle made by Fabrique Nationale.

A Venezuelan contract Model 1924/30 rifle made by Fabrique Nationale.

FN also supplied actions to British sporting rifle manufacturers and

made large numbers of ‘98 Mauser rifles and actions for the American

market, which were sold through companies like Browning, Colt,

Harrington & Richardson, High Standard and Weatherby.

An early Weatherby sporting rifle made on an FN Mauser 98 action.

An early Weatherby sporting rifle made on an FN Mauser 98 action.

FN’s other famous association would be John Browning, with the

company responsible for taking on and developing many of his designs,

such as the Hi Power pistol.

FN lives on today as FN Herstal and FN America, with FN products, like

the M240 and M249 in service with the U.S. military, along with firearms

for the civilian and law enforcement markets, like the 509 handgun.

Nine: Mauser Didn’t Invent The 8 mm Mauser…But They Did Design Two Other Important Cartridges

Though the most famous cartridge associated with Mauser is the 8x57

mm, it was not, in fact, designed by the company, but was developed by

the same team that came up with the ‘88 Commission Rifle.

While Mauser designed a plethora of propriety cartridges, two in

particular are notable. Their first smokeless powder, high-velocity

round was the 7.65x53 mm, as introduced in the 1889 Belgian Mauser. It

went on to be one of the most widely-used military cartridges of the

early 20th century. In Europe, along with the Belgians, Spain and Turkey

used the cartridges in their Mauser rifles. The 7.65x53 mm Mauser was

extremely popular in South American countries

and would go on to be chambered in many machine guns, from the Maxim to

the ZB-30, along with more modern rifles, like the semi-automatic FN-49.

An Argentinean contract Model 1891 Mauser carbine in 7.65x53 mm.

An Argentinean contract Model 1891 Mauser carbine in 7.65x53 mm.

In 1892, Mauser introduced the 7x57 mm

cartridge along with an improved rifle that featured an internal,

staggered-column magazine and non-rotating extractor that all subsequent

Mausers would use. The 7x57 mm would also become a popular military

cartridge in Spain, Mexico and South America and was used in firearms

designs from the Remington Rolling Block to the Mondragón semi-automatic

rifle.

A

Spanish contract Model 1893 Mauser chambered in 7x57 mm cartridge,

which featured a staggered-column, flush box magazine for the first time

in a Mauser design.

A

Spanish contract Model 1893 Mauser chambered in 7x57 mm cartridge,

which featured a staggered-column, flush box magazine for the first time

in a Mauser design.

The 7x57 mm Mauser

was nearly as popular in the sporting world as it was in military

circles. Besides being prevalent on the European continent (it was one

of the most popular chamberings for factory Mauser sporters), it hopped

the Channel and made great inroads with British sporting rifle makers.

The Rigby firm was one of the earliest to adopt the Mauser action and

the 7 mm cartridge, which it re-christened the “.275 Rigby.” Though an

excellent cartridge for thin-skinned, medium-sized game, some British

hunters pushed their luck. The 7x57 mm was W.D.M. “Karamojo” Bell’s

favorite cartridge for elephants, and Jim Corbett used the round to

dispatch several of the famous man-eating tigers he went after.

The 7x57 mm was an extremely popular hunting cartridge, especially in rifles like this Mauser factory-made Model B.

The 7x57 mm was an extremely popular hunting cartridge, especially in rifles like this Mauser factory-made Model B.

The 7x57 mm also made its way to the U.S. and by the 1930s, Remington

and Winchester were chambering their bolt action rifles in the

cartridge. Though, by the 1960s, most American manufacturers had

discontinued 7x57 mm as a standard chambering, they continued to

occasionally do special runs in the caliber, in rifles like the the

Remington Model 700 and Ruger 77. The 7x57 mm case would also serve as

the basis for an equally popular American cartridge, the .257 Roberts.

Ten: Handguns Were An Important Part Of Mauser’s Business

A “Red 9” Mauser C96 pistol chambered in 9 mm Parabellum.

A “Red 9” Mauser C96 pistol chambered in 9 mm Parabellum.

Though the Mauser name is synonymous with rifles, handguns

were also an important part of its business. Their first

semi-automatic, and most well-known, handgun was the C96 pistol. Though

never officially adopted by the German Army, 150,000 “Broomhandle”

pistols would be purchased by them to supplement the P08 “Luger” in

World War I. By the time production ended in 1937, more than a million

C96 handguns had been produced by Mauser, along with countless copies made in other parts of the world.

After the war, Mauser delved into the pocket pistol market, making a variety of designs in .25 and .32 ACP. To compete with more modern designs, like the Walther PPK, Mauser introduced the HSc

in 1940, with a double-action trigger and clean external lines. Many of

Mauser’s pocket pistols would serve the German military and police.

A Mauser HSc pistol in .32 Auto that was made for a German military contract and captured by an American G.I.

A Mauser HSc pistol in .32 Auto that was made for a German military contract and captured by an American G.I.

Though they failed to secure adoption of one of their full-size

designs, Mauser made many 9 mm Parabellum handguns for the German

military. In 1930, they were contracted to make P08 Lugers and would continue to do so until 1943. Mauser would be the second largest producer of the Walther P38, during World War II.

The

“BYF” markings on this P08 Luger (left) and P38 (right) indicate they

were manufactured at the Mauser factory during World War II.

The

“BYF” markings on this P08 Luger (left) and P38 (right) indicate they

were manufactured at the Mauser factory during World War II.

After Mauser was reorganized following the war, they re-started Luger

production in 1969 and continued making the pistols until 1986. The

latest handguns marketed by Mauser were High Power clones they sold

between 1992 and 1996, which were made for them by FEG of Hungary.

A post-World War II P08 Luger manufactured for Interarms by Mauser.

A post-World War II P08 Luger manufactured for Interarms by Mauser.

Denmark

and Sweden, represented here by Swedish Air Force Saab Gripens

(foreground) and Danish Air Force F-16s, have pledged to raise defense

spending to 2% of GDP.

Denmark

and Sweden, represented here by Swedish Air Force Saab Gripens

(foreground) and Danish Air Force F-16s, have pledged to raise defense

spending to 2% of GDP.

Brothers Wilhelm Mauser (right) and Paul Mauser (left).

Brothers Wilhelm Mauser (right) and Paul Mauser (left). The Mauser factory in Oberndorf am Neckar in 1910.

The Mauser factory in Oberndorf am Neckar in 1910. A Model 1860 Dreyse Needle Gun with its bolt handle visible.

A Model 1860 Dreyse Needle Gun with its bolt handle visible. The Greene breechloading bolt-action rifle from the Civil War era.

The Greene breechloading bolt-action rifle from the Civil War era. The action of the Greene, showing its turning bolt mechanism and locking lugs.

The action of the Greene, showing its turning bolt mechanism and locking lugs. The action of the Interim Model 1869/70, a prototype that would lead to the first successful Mauser, the M1871.

The action of the Interim Model 1869/70, a prototype that would lead to the first successful Mauser, the M1871. Mauser’s first successful model, the 1871, was a single-shot that fired a blackpowder cartridge.

Mauser’s first successful model, the 1871, was a single-shot that fired a blackpowder cartridge. Mauser’s first U.S. patent for “Improvements in Breech Loading Firearms.”

Mauser’s first U.S. patent for “Improvements in Breech Loading Firearms.”  A 1915 Mauser patent for semi-automatic pistol design (right) and a 1906 Mauser patent for a rifle magazine (left).

A 1915 Mauser patent for semi-automatic pistol design (right) and a 1906 Mauser patent for a rifle magazine (left). An early Mauser-Norris prototype, showing the action opened.

An early Mauser-Norris prototype, showing the action opened. A Model 1888 Commission rifle made at the Amberg arsenal.

A Model 1888 Commission rifle made at the Amberg arsenal. A

Model 1888 Commission rifle action (top) compared to a 1903/14 Greek

Mannlicher (center) and a 1903 Mannlicher Schoenauer sporting rifle

(bottom).

A

Model 1888 Commission rifle action (top) compared to a 1903/14 Greek

Mannlicher (center) and a 1903 Mannlicher Schoenauer sporting rifle

(bottom). A Mauser Model 1896 “Broomhandle” semi-automatic pistol.

A Mauser Model 1896 “Broomhandle” semi-automatic pistol. The Mauser Model 1878 “Zig-Zag” revolver.

The Mauser Model 1878 “Zig-Zag” revolver. A Mauser C77 single-shot pistol with the action closed (right) and opened for loading (left).

A Mauser C77 single-shot pistol with the action closed (right) and opened for loading (left). A

Belgian Model 1889 Mauser action with the barrel jacket removed,

showing a stripper clip, or charger, of cartridges inserted into the

action.

A

Belgian Model 1889 Mauser action with the barrel jacket removed,

showing a stripper clip, or charger, of cartridges inserted into the

action. A Venezuelan contract Model 1924/30 rifle made by Fabrique Nationale.

A Venezuelan contract Model 1924/30 rifle made by Fabrique Nationale. An early Weatherby sporting rifle made on an FN Mauser 98 action.

An early Weatherby sporting rifle made on an FN Mauser 98 action. An Argentinean contract Model 1891 Mauser carbine in 7.65x53 mm.

An Argentinean contract Model 1891 Mauser carbine in 7.65x53 mm. A

Spanish contract Model 1893 Mauser chambered in 7x57 mm cartridge,

which featured a staggered-column, flush box magazine for the first time

in a Mauser design.

A

Spanish contract Model 1893 Mauser chambered in 7x57 mm cartridge,

which featured a staggered-column, flush box magazine for the first time

in a Mauser design. The 7x57 mm was an extremely popular hunting cartridge, especially in rifles like this Mauser factory-made Model B.

The 7x57 mm was an extremely popular hunting cartridge, especially in rifles like this Mauser factory-made Model B. A “Red 9” Mauser C96 pistol chambered in 9 mm Parabellum.

A “Red 9” Mauser C96 pistol chambered in 9 mm Parabellum. A Mauser HSc pistol in .32 Auto that was made for a German military contract and captured by an American G.I.

A Mauser HSc pistol in .32 Auto that was made for a German military contract and captured by an American G.I. The

“BYF” markings on this P08 Luger (left) and P38 (right) indicate they

were manufactured at the Mauser factory during World War II.

The

“BYF” markings on this P08 Luger (left) and P38 (right) indicate they

were manufactured at the Mauser factory during World War II.  A post-World War II P08 Luger manufactured for Interarms by Mauser.

A post-World War II P08 Luger manufactured for Interarms by Mauser.