I clipped this from "American Rifleman", I thought it was a great story, I have or had a 1903 pattern rifle before I lost her in the great kayak mishap*sniff*Sniff*, the same time I lost my lamented Garand

Here they are during happier times before the Kayak mishap*Sniff*Sniff*. Perhaps one day....the happier times will return, and I can look at ownership again. The story behind this was really neat.

“December 7th, 1941, a date which will live in infamy, the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan,” as said by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in Congress on Dec. 8, 1941. The suprise attack on Pearl Harbor, one of the most pivotal moments in United States history, severely crippled the fighting capabilities of the Pacific Fleet for the onset of World War II. After the attack, monumental efforts went into rescuing men still trapped on the sunken vessels and salvaging material from the wrecks. Now, 80 years later, three rifles salvaged from the U.S.S. California have been discovered by the Archival Research Group and can be documented to this recovery operation following the attacks on Pearl Harbor.

The U.S.S. California, BB-44, was a one of two Tennessee Class "super-dreadnought" battleships built by United States Navy during World War I and completed after the war. Launched in November 1919, the ship was over 600' long, weighed over 30,000 tons and was armed with 12 14" naval guns. After being commissioned in 1921, U.S.S. California became the flagship of the U.S. Pacific Battle Fleet and, along with her sister-ship U.S.S. Tennessee, helped form the backbone of the U.S. Navy's modern battle line during the inter-war period. She was nicknamed “The Old Prune Barge,” due to the large amount of prunes her namesake state of California produced at the time. In 1940, she also became one of the first battleships in the U.S. Navy to be fitted with radar.

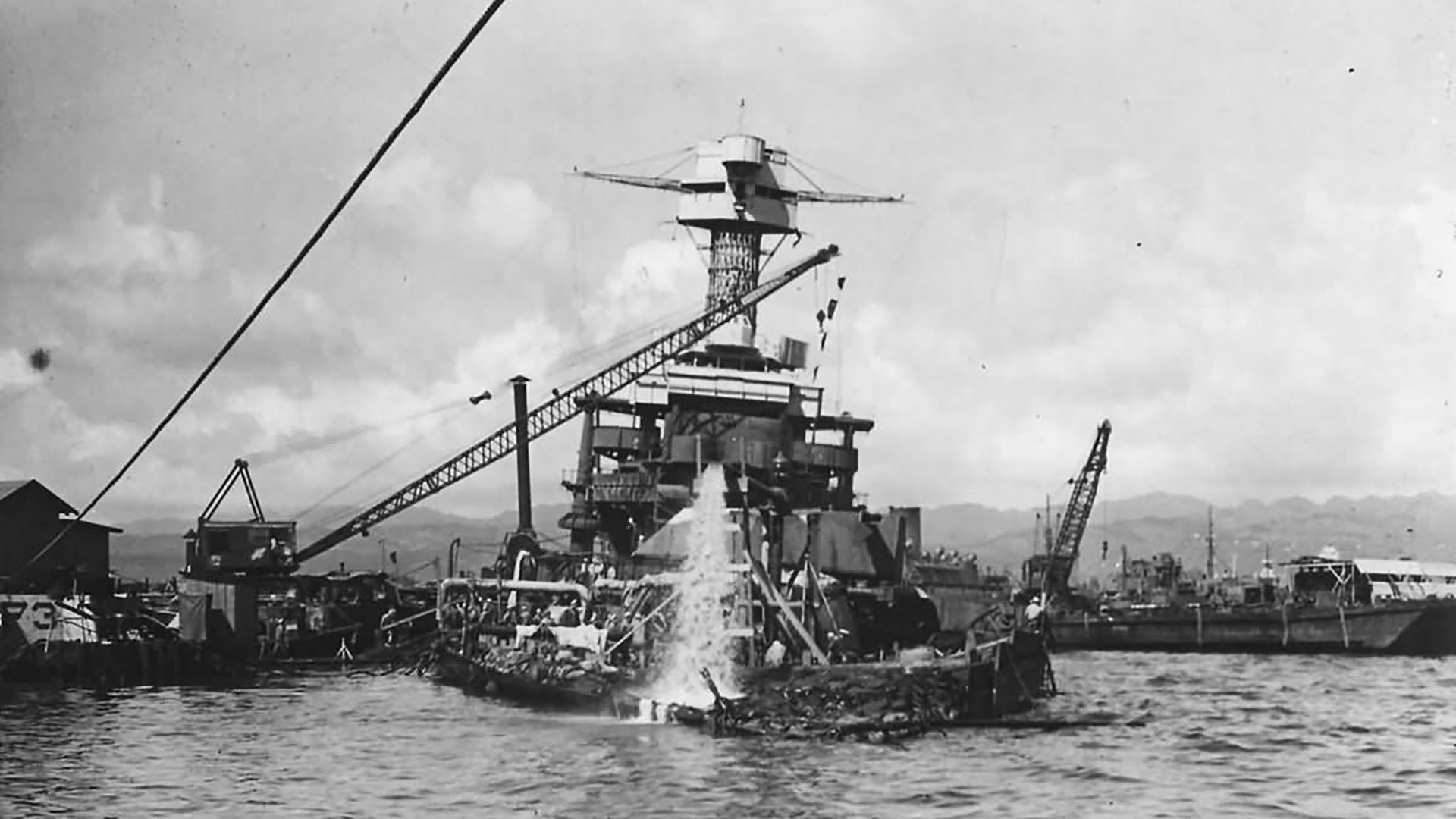

The U.S.S. California (BB-44) sinking at her moorings next to Ford Island during the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941. The ship is low in the water and listing to the port side after suffering two torpedo hits. In the background, the destroyer U.S.S. Shaw burns and the stricken battleship U.S.S. Nevada begins to beach herself at Hospital Point.

The U.S.S. California (BB-44) sinking at her moorings next to Ford Island during the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941. The ship is low in the water and listing to the port side after suffering two torpedo hits. In the background, the destroyer U.S.S. Shaw burns and the stricken battleship U.S.S. Nevada begins to beach herself at Hospital Point.

On Sunday morning, Dec. 7, 1941, U.S.S. California was moored alone near the southeastern end of Ford Island in Pearl Harbor, just ahead of the fleet oiler U.S.S. Neosho and "Battleship Row." When the first wave of the attack began, the senior officer onboard roused the crew to general quarters and ordered preparations to get the ship underway. Gun crews rushed to their 5" and .50-cal. anti-aircraft armaments and began firing back at the swarming Japanese warplanes as they made strafing runs and dropped bombs. However, the ready use ammunition kept around the anti-aircraft batteries was limited and the ammunition magazines had to be unlocked.

While the ship was still attached to her moorings, two Japanese Nakajima B5N "Kate" torpedo bombers approached from the southeast and released their ordnance, with both striking on the port side. The resulting explosions ripped massive holes into the U.S.S. California's hull under the waterline, compromising several internal compartments and structures. She immediately began to take on large volumes of water and heel to the port side, with the flooding only worsened by the fact that many below-deck hatches and doors had been left open for inspection.

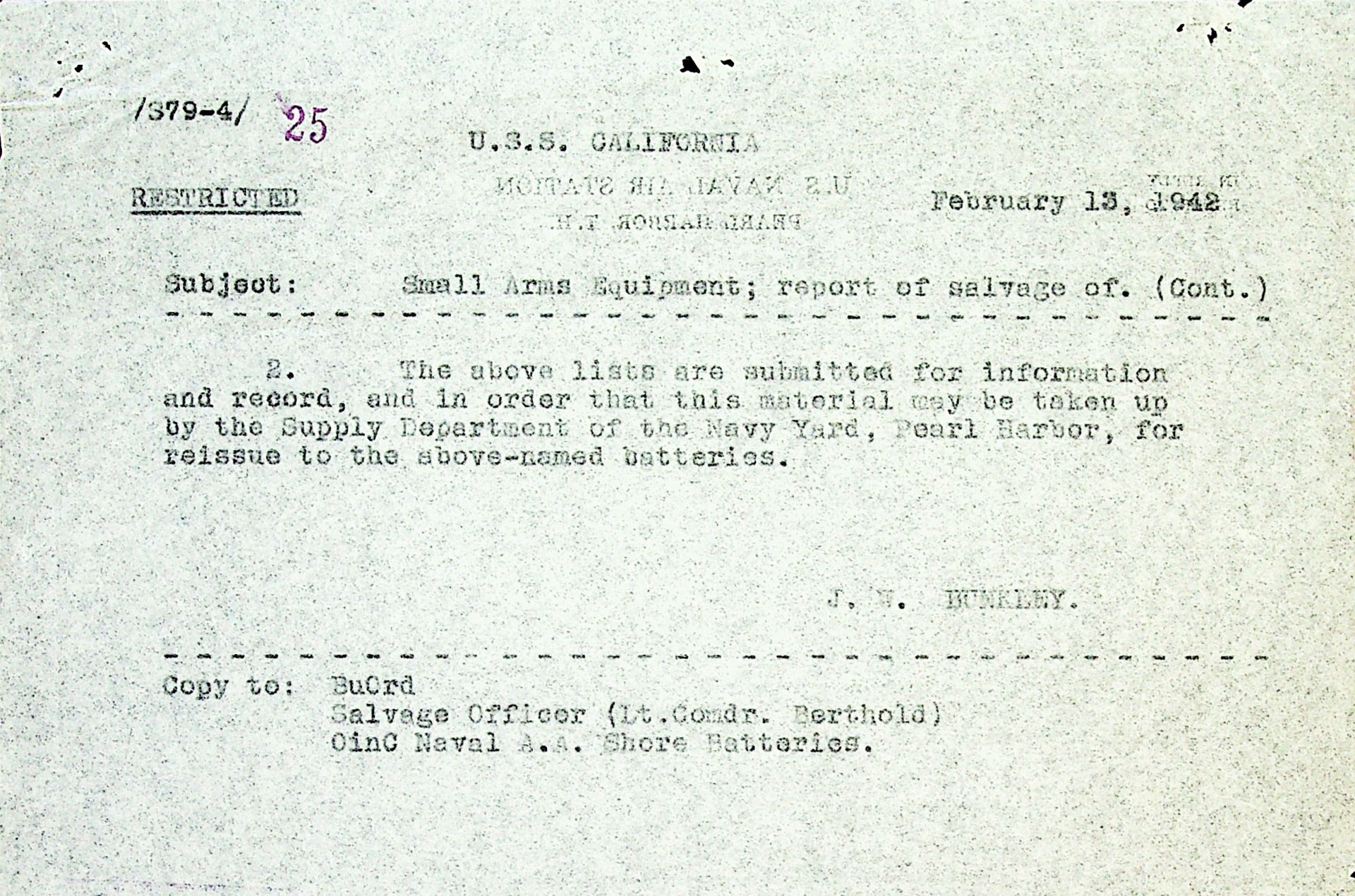

A photo of salvage operations underway on the wreck of U.S.S. California after the attack. Note how low the main deck is in the water, along with the water being pumped out of the hull. As the U.S.S. California settled onto bottom of Pearl Harbor, the hull began to sink down ever deeper into a silt embankment, necessitating the removal of usable materials and extra weight from the ship. This included the removal of the ship's 14" naval guns, which are already missing from the turrets in this photo.

A photo of salvage operations underway on the wreck of U.S.S. California after the attack. Note how low the main deck is in the water, along with the water being pumped out of the hull. As the U.S.S. California settled onto bottom of Pearl Harbor, the hull began to sink down ever deeper into a silt embankment, necessitating the removal of usable materials and extra weight from the ship. This included the removal of the ship's 14" naval guns, which are already missing from the turrets in this photo.

Uncontrolled flooding spread through the port side compartments and the order was given to counter flood on the starboard side, in a desperate effort to keep the ship upright. To make matters worse, water entered the fuel lines and the ship lost power. As the crew fought to save the ship, Japanese Aichi D3A "Val" dive bombers made repeated attacks on the stricken vessel, scoring a bomb hit and two near misses that started fires and caused further damage. Dead in the water, U.S.S. California burned and began to slowly sink. Despite the efforts of the crew, surrounding vessels and portable pumps, the ship slowly settled into the mud of harbor bottom over the next three days, mostly upright with only her main deck and super-structure remaining above the waterline.

After the attack, extensive efforts were made to save men still trapped on the sunken vessels and salvage whatever equipment remained usable. Evaluations on the sunken ships were also conducted to determine if any could be raised and brought back into service. Of the four battleships sunk at Pearl Harbor, the U.S.S. California was the least damaged overall and prioritized for salvage. However, despite resting is the mud, the ship's hull began to sink even deeper into a silt embankment on the harbor bottom. Furthermore, the longer equipment still onboard the ship was exposed to the harbor's salty tropic waters, the less usable it would rapidly become. These factors necessitated efforts to remove extra weight and any usable materials from the ship as quickly as possible, including the removal of the ship's 14" naval guns from their turrets.

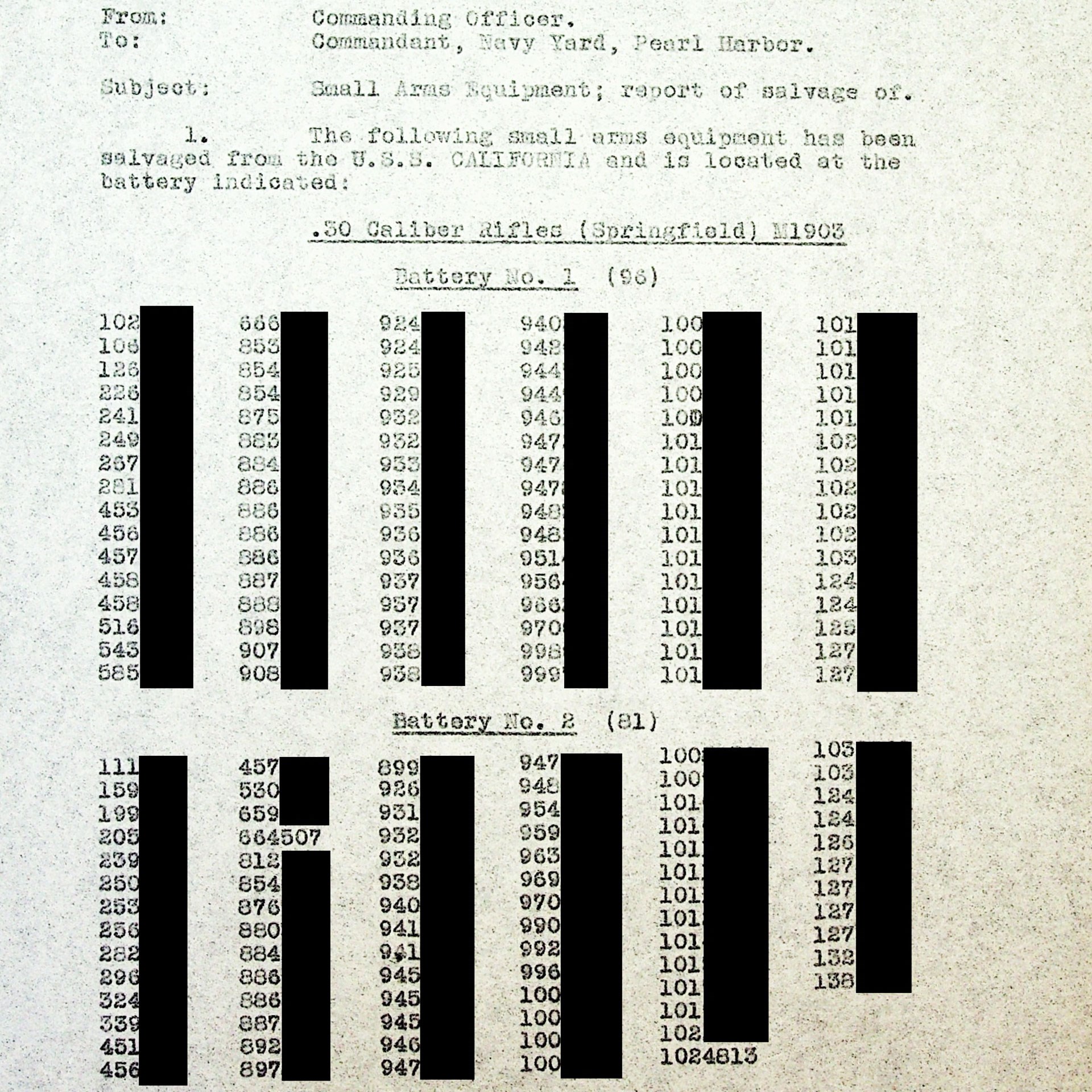

A page of the memorandum in which Capt. Joel Bunkley documents the transfer of the small arms to the Supply Department of the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

A page of the memorandum in which Capt. Joel Bunkley documents the transfer of the small arms to the Supply Department of the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

Other equipment of varying size, from the ship's radar to ammunition, was also salvaged. This included the recovery of the many small arms which were still stored in various armories below deck. Yet, what happened to these small arms that were recovered from the wreck since then? This is where documentation from the National Archives expands further. On a memorandum dated Feb. 13, 1942, Capt. Joel Bunkley wrote to the commandant of the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard to transfer the small arms salvaged from the U.S.S. California to various coastal artillery batteries located around the island of Oahu, Hawaii.

This transfer included 352 M1903 rifles, 53 M1911 pistols, 26 Browning Automatic Rifles, 16 Lewis machine guns and two Thompson submachine guns. The lists of serial numbers for the M1903 rifles in the memorandum does not specify whether the rifles are of Springfield Armory or Rock Island Arsenal manufacture. However, all are serial numbers exclusive to Springfield Armory production and above the range of duplicate serial numbers (Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal bearing the same serial number on the receiver). The serial numbers were also recorded in ascending order, making it easier to see trends in serial number ranges present.

The first page from a list of rifle serial numbers from the commanding officer of the U.S.S. California, transferring salvaged property to the commandant of the Navy Yard of Pearl Harbor. Note rifle S/Ns 664504 and 1024813 are contained in the list of rifles sent to Battery No.2. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

The first page from a list of rifle serial numbers from the commanding officer of the U.S.S. California, transferring salvaged property to the commandant of the Navy Yard of Pearl Harbor. Note rifle S/Ns 664504 and 1024813 are contained in the list of rifles sent to Battery No.2. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

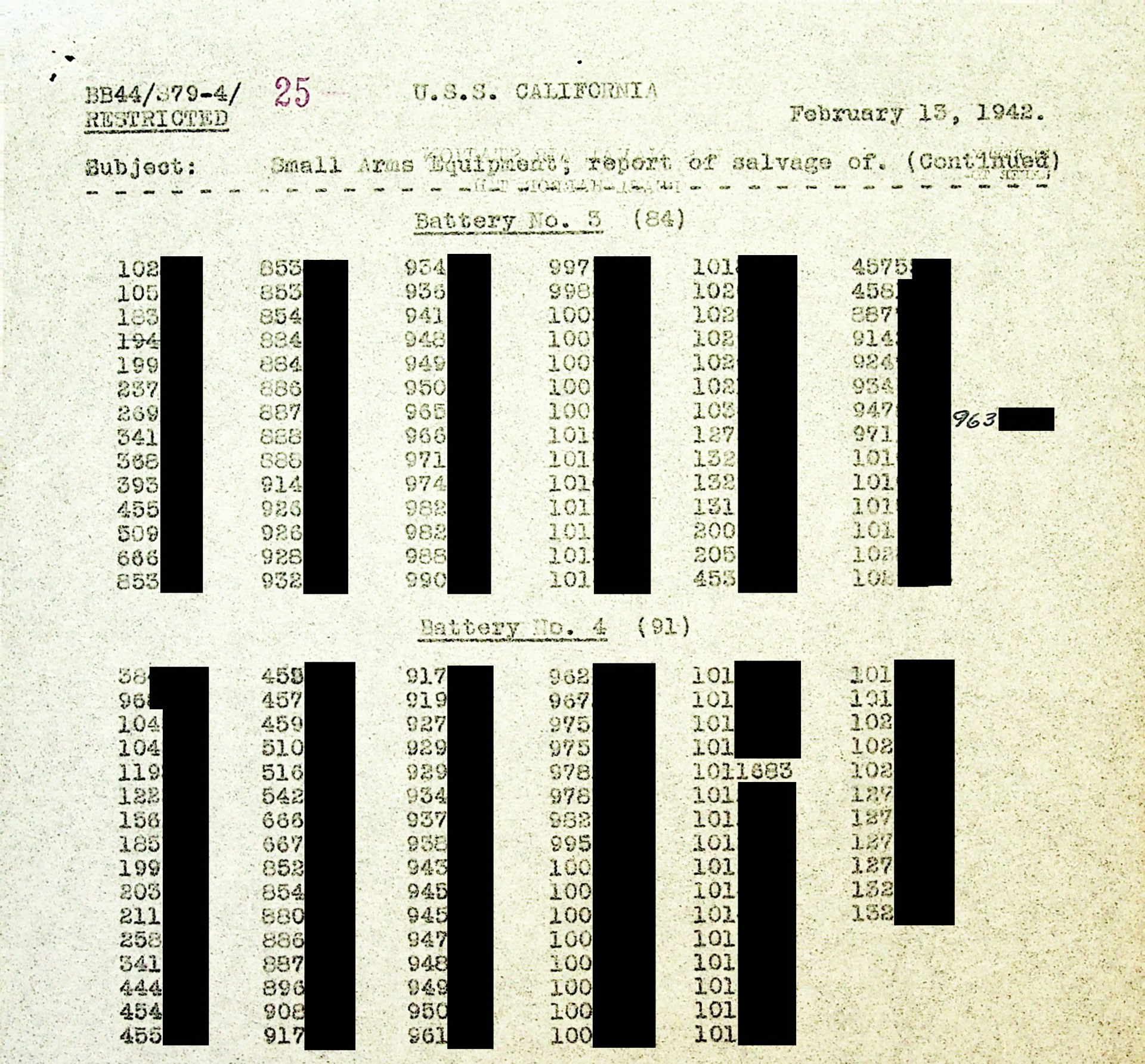

The second page of the list of M1903 rifle serial numbers recovered from the wreck of the U.S.S. California, with rifle S/N 1011683 transferred to Battery No. 4. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

The second page of the list of M1903 rifle serial numbers recovered from the wreck of the U.S.S. California, with rifle S/N 1011683 transferred to Battery No. 4. Photo courtesy of Archival Research Group.

In the aftermath of the attack, the Territory of Hawaii was in a state of emergancy and security across the archipelago was put on high alert. Eight defensive batteries were hastily constructed around the island of Oahu to offer better protection against further seaborne attacks and even possible invasion. The salvaged M1903 rifles that came from the U.S.S. California were only sent to batteries one through four, with battery one receiving 96, battery two receiving 81, battery three receiving 84 and battery four receiving 91 of the rifles. The authors of this article have compiled a table of these eight coastal defense batteries built around the island, along with armament type and notes regarding each:

Battery Number | Location | Type | Notes |

| No.1 | Hickam Field | Four 5" Naval Guns | Located at Hickam Village housing complex. No remains. |

| No.2 | Waipahu | Four 5" Naval Guns | Located in a sugarcane field somewhere in the West Loch vicinity. |

| No.3 | Fort Weaver (Puuloa) | Four 5" Naval Guns | Most likely located adjacent to the Navy’s Fleet Machine Gun Training School. Marines here manned three batteries of .50-cal. anti-aircraft machine guns when the Japanese attacked on Dec. 7. This area was developed for housing in the 1950’s, adjacent to the present-day Marine Corps Puuloa Rifle Range. |

| No.4 | Ewa Marine Corps Air Station | Four 5" Naval Guns | No remains, site developed. |

| No.5 | Ahua Point | Four 5" Naval Guns | Searchlights were emplaced here, as well as an anti-aircraft warning station (AAIS 10) (1940). No remains of any military structures. |

| No.6 | Waipio (Pearl Harbor Naval Base) | Four 5" Naval Guns | Located on the point halfway on the eastside of the Waipio Peninsula along the shore of the Middle Loch. Also included a mobile 3" anti-aircraft gun battery. Two concrete gun emplacements, the power generator house and fire-control switchboard room. |

| No.7 | Pearl Harbor (Ford Island) | Four 5" Naval Guns | Under the command of Fort Kamehameha. |

| No.8 | Aiea Heights | Four 5" Naval Guns | Hawaiian Anti-Aircraft Command, command post was located here. |

In the 80 years that have passed since the attack, the history of these rifles and their whereabouts was largely forgotten and began to fade. Yet, thanks to the patient efforts of the Archival Research Group and the information discovered in Capt. Bunkley's 1942 memorandum, three of these salvaged rifles have been identified. These three M1903 rifles appear in the memorandum by serial number as being recovered from the U.S.S. California, and all three were carefully examined by the authors for any interesting features or details. A table with some of technical details of these M1903 rifles is below:

| Rifle S/N | Bolt | Stock | Disposition after salvage from U.S.S. California |

| 664507 | J5 | Finger grasping groove with two stock screws. No inspector marks remain. | Battery No.2 |

| 1011683 | J5 | Finger grasping groove with two stock screws. J.S.A. inspected. | Battery No.4 |

| 1024813 | J5 | Finger grasping groove with two stock screws. D.A.L. inspected, followed by S.A./J.F.C. re-arsenal stamp. | Battery No.2 |

Of the three rifles examined, the lowest numbered, S/N 664507, does not appear in like-new condition, but also does not show signs of extensive surface corrosion or pitting on its metal components. Meanwhile, S/N 1011683 is in an almost like-new condition. It exhibits many features of a non-rebuilt rifle with original finish, with both the metal and wood being in good condition with honest wear and patina, but no signs of water damage. As for S/N 1024813, while its stock and some other parts display signs of being rebuilt by Springfield Armory after the war, it still bears the original receiver finish and has no surface pitting.

When examining these rifles, a question that comes up is: “Why are these rifles not showing signs of salt-water damage?” Unfortunately, the documentation does not specify when exactly during the salvaging operations that these small arms were recovered. Without the confirmation of primary documentation, it theoretically could have been hours, days, or even weeks following the sinking that these small arms were removed. But, considering the intensity of the salvage operation and the conditions concerning the ship, the removal of such items would have been an urgent issue. With the observable conditions of the three rifles, it is likely these small arms were retrieved from the U.S.S. California before the damaging effects of salt-water corrosion could set in.

M1903 S/N 664507.

M1903 S/N 664507.

The memo also does not state the conditions of the armories when the rifles were retrieved, that is, if they were in a partially flooded section or in a dry section. Furthermore, it does not provide any information as the the location or designations of the armories onboard the ship. Yet, these locations where the small arms were stored could have played a big factor in the rifles’ good condition. If the armories were located on the upper decks, they could have been unaffected by flooding due to the ship sinking in shallow water. Also, despite the fact that many watertight doors had been left open during the attack, the crew did manage to close a substantial number and there were lower compartments of the ship that remained water tight even after the sinking.

M1903 S/N 664507 does show some signs of light pitting and the sort of corrosion one would expect from a rifle that was salvaged from a wrecked vessel in a tropical harbor. However, S/Ns 1011683 and 1024813 do not show similar signs of corrosion. At the present time, it is unknown as to whether S/N 664507’s corrosion is linked to Pearl Harbor’s salt water or not. With the U.S.S. California out of action for the foreseeable future, the rifles were perfect candidates for redistribution to the island defenses. Thus, it is also reasonable to speculate that, due to the state of emergency on Oahu, they could have been prioritized to be removed immediately.

M1903 S/N 1011683.

M1903 S/N 1011683.

When viewed through the lens of 2021, it is rather difficult to imagine a land invasion by Japanese troops on the island of Oahu after the attack. It is clear now that invasion was never an immediate strategic intention of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Yet, the strategic intentions of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army were still unknown at the time. With the fear of a possible invasion looming, it is easy to understand why all weapons would be prioritized for reissue to bolster defenses around the island. However, this prioritization is not directly stipulated in the correspondence.

The details on the memorandum have also caused some confusion in its interpretation. Some have interpreted, based off the four "batteries" listed on the documents, that these small arms were salvaged from the ship's four main gun turrets and barbettes. Understanding Naval terminology can offer some additional clarification. A battleship’s armaments of the time were often referred to as primary and secondary "batteries," and the U.S.S. California did have four main battery turrets. However, these positions only serviced and housed the ship's larger caliber weapons. The term battery can also refer to a grouping of artillery or other large-caliber armaments in an established position, as is the case with the four defensive positions on the island the rifles were sent to.

M1903 S/N 1024813.

M1903 S/N 1024813.

Some historians have debated whether these rifles were used by Navy personnel or the Marine detachment while aboard the U.S.S. California. These rifles would almost certainly have been for issuance to the naval personnel and landing parties. At the time, the common practice for the Marine detachment was to bring aboard, maintain and handle their own small arms. The responsibility for these arms belonged to the commanding officer of the Marine detachment, not the captain of the ship. Thus, it seems unlikely that these rifles were from the marine detachment.

The next question that should be addressed is: "Why does a battleship even need small arms aboard?" The naval landing party would augment the Marine detachment aboard the ship when needed. It consisted of sailors who were normally assigned roles that were not crucial for the ship's operational needs. The primary role of these armed sailors was to function as the ship’s security. Though, this should not be confused with policing onboard the ship.

Landing party members aboard the U.S.S. California, sometime in the late 1920s to early 1930s. The U.S.S. California's sister-ship, the U.S.S. Tennessee, can be seen in the background. Take notice of the two Marine officers supervising the formation. It is reasonable to believe that the rifles we've examined may be shouldered by one of these sailors.

Landing party members aboard the U.S.S. California, sometime in the late 1920s to early 1930s. The U.S.S. California's sister-ship, the U.S.S. Tennessee, can be seen in the background. Take notice of the two Marine officers supervising the formation. It is reasonable to believe that the rifles we've examined may be shouldered by one of these sailors.

Naval personnel of the landing party would occasionally combine with the Marine detachment to form a larger landing force in certain situations, such as securing and stabilizing a hostile port. One example of the use of combined landing parties was the United States' occupation of Veracruz. The Marine detachment was also tasked with training the naval personnel in infantry tactics. It should also be noted that the Marines and Navy had separate armories for maintaining, repairing and storing their small arms. They only combined for training and carrying out landing party operations.

After the small arms were salvaged and sent to their respective batteries, it remains unclear what, if any, further service these rifles saw. It is possible that they sat out the rest of the war at the batteries, were transferred onto active duty ships, used for training or sent elsewhere. The U.S. Navy did not adopt the M1 Garand service rifle until September 1945, and the M1903 rifle was declared obsolete in 1947.

A view of the markings in the stock of M1903 S/N 1024813. Note the original D.A.L. inspector stamp followed by a post-war Springfield Armory S.A./J.F.C. rebuild cartouche as well as the added "Hatcher" hole in the receiver.

A view of the markings in the stock of M1903 S/N 1024813. Note the original D.A.L. inspector stamp followed by a post-war Springfield Armory S.A./J.F.C. rebuild cartouche as well as the added "Hatcher" hole in the receiver.

Thus, it is possible that these rifles could have served in other roles during the war, but that is unknown at the present time. It's also possible that these rifles were withdrawn from service sometime before or around the official adoption date of the M1 by the Navy in 1945, or shortly after the M1903 was declared obsolete. However, the presence of a Springfield Armory S.A./J.F.C. cartouche from a post-war rebuild in the stock of S/N 1024813 might indicate possible use into the 1950s.

As for the U.S.S California, her story did not end in the mud of Pearl Harbor. After extensive efforts to patch the two torpedo holes and regain buoyancy, she was re-floated in March 1942. In October 1942, she sailed for Puget Sound Naval Yard, Wash., for long-term repairs and reconstruction. While being repaired, the ship was modernized and refitted with a new superstructure, radars and anti-aircraft mounts. Finally, on Jan. 31, 1944, the rebuild was completed, and she underwent a series of sea trials before rejoining the Pacific Fleet.

The U.S.S. California underway in 1944 after her extensive repairs and rebuild at Puget Sound Naval Yard, Wash. Note the redesigned superstructure, added radars and anti-aircraft mounts.

The U.S.S. California underway in 1944 after her extensive repairs and rebuild at Puget Sound Naval Yard, Wash. Note the redesigned superstructure, added radars and anti-aircraft mounts.

Back in the fight, U.S.S. California’s battle record included the invasions of the Saipan, Guam and Tinian in the summer of that year. In October 1944, the ship took part in the largest naval battle of World War II, the Battle of Leyte Gulf in the Philippines. On the night of Oct. 25, 1944, a U.S. naval force under the command of Rear Adm. Jesse Oldendorf, which included the Pearl Harbor veteran battleships U.S.S. California, U.S.S. West Virginia and U.S.S. Tennessee, encountered a Japanese battle line sailing up the Surigo Strait.

The Japanese force, commanded by Vice Adm. Shoji Nishimura and comprised of the battleships I.J.N. Fuso, I.J.N. Yamashiro and the heavy cruiser I.J.N. Mogami, attempted to sneak up the strait toward U.S. amphibious forces landing on the island of Leyte. In the ensuing battle, the U.S. battleships crossed the enemy's "T" and opened fire with devastating accuracy, thanks to their radar-guided gunnery. All three Japanese ships were lost during this engagement, and it marked the final gun dual between battleships in naval history. U.S.S. California served for the remainder of the war in the Pacific, before being decommissioned in 1947 and placed in reserve. She and her sister-ship remained in mothballs until being scrapped in 1959.

Another view of M1903 S/N 1024813.

Another view of M1903 S/N 1024813.

It is often said in the firearm collecting community: “Buy the rifle and not the story.” These words are commonly repeated almost as a mantra when advising fellow collectors on the most intriguing of backstories attached to prospective purchases. Specifically, this advise aims to help avoid a costly mistake. Many stories attached to old arms with a price tag are typically just that, stories that cannot be validated.

These three rifles serve as the exception to that rule, and show that one can in fact accept and prove a story with primary source documentation. Their unique history would have been lost, had the connection not been made between the respective serial numbers and the 1942 memorandum obtained at the National Archives. They also serve as a humble reminder of one of the darkest moments in U.S. history, as 98 men perished onboard the U.S.S. California during the attack. For more information on other serial numbers of small arms salvaged from the U.S.S. California and other documentation, visit archivalresearchgroup.com.

Provenance CAN make a significant difference in value, IF it is valid. Sadly, even that is being faked today.

ReplyDeleteHey Old NFO;

Deleteits a bummer, I hope it is accurate because of the "Neatness" factor.