I cribbed this from the "Art of Manliness", This is something people

can learn, especially the young that seem to think that the more noise

they make the more they are respected. Sometimes Silence is Golden.

" Never complain; never explain."

" Never complain; never explain."

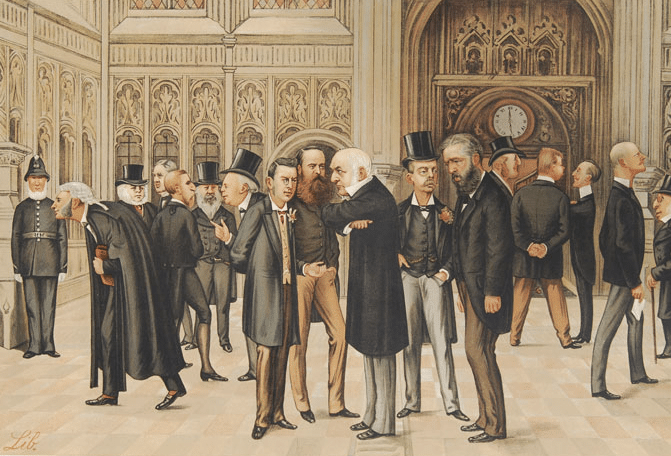

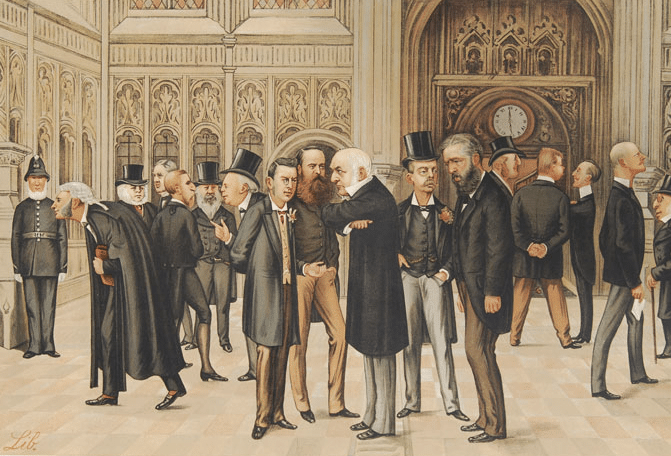

This pithy little maxim was first coined by the British politician

and prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, and adopted as a motto by many

other high-ranking Brits — from members of royalty, to navy admirals, to

fellow prime ministers Stanley Baldwin and Winston Churchill. The maxim

well encapsulates the stiff-upper lipped-ness of the Victorian age, but

the timeless wisdom it contains has made it a guiding mantra of

powerful, confident, accountability-prizing men up through the modern

day.

The “nevers” of course aren’t ironclad and don’t apply to every situation, and even when they

should apply,

they can be hard to follow through on! But understanding when, where,

and why to apply this maxim is truly a great help in becoming a more

autonomous and assertive man.

Its four words pack a lot of truth in a small space and work on a few

different levels. So let’s unpack them, starting with the meat of the

matter — “never explain” — and working backwards.

“Never explain — your friends do not need it, and your enemies will not believe you anyway.” –Elbert Hubbard

When Winston Churchill was a young cavalry

officer, he was always looking for ways to get to the front and

experience battle firsthand. With much persistence, he eventually

secured a position in the field as a personal attendant to Sir William

Lockhart, who was overseeing the British military’s campaigns in what is

now Pakistan. When Churchill first joined the general’s staff, he

“behaved and was treated as befitted my youth and subordinate station.”

But then one day he saw an opportunity to offer a bit of advice that led

to him being “taken much more into the confidential circles of the

staff” and “treated as if I were quite a grown-up.”

Churchill heard that the general and his headquarters staff had been

hurt and angry to hear that a newspaper correspondent who had been sent

home from their camp had published a very critical article about one of

their recent campaigns. The officers smarted at what they felt were

unfair charges, and the Chief of Staff had written up a thorough

rebuttal and mailed it off to the newspaper to be published. Churchill

at once spoke up and tried to convince the staff that such a move was

ultimately a bad idea, and that the piece ought to be intercepted before

it was ever printed:

“I said that it would be considered most undignified and

even improper for a high officer on the Staff of the Army in the Field

to enter into newspaper controversy about the conduct of operations with

a dismissed war-correspondent; that I was sure the Government would be

surprised, and the War Office furious; that the Army Staff were expected

to leave their defence to their superiors or to the politicians; and that no matter how good the arguments were, the mere fact of advancing them would be everywhere taken as a sign of weakness.”

In this,

as in many things,

Churchill turned out to be quite prescient and wise. Offering

explanations does indeed demonstrate weakness, for several reasons:

Explaining gives power to another.

When someone criticizes or insults you, gets offended by something you

do or say, or questions your decisions and why you’ve chosen to do

something a certain way, it’s natural to want to explain why you think

they’re wrong — especially if said party has impinged on your integrity

or honor. And some kind of response may indeed be in order.

If the person is someone you know and respect as an equal — someone you consider to be inside your

“circle of honor”

— and they have said something intelligent and interesting, you may

want to explain yourself in order to invite further discussion.

If they’re your boss or a customer, you may need to offer an explanation to hold onto your job or their business.

If they’re someone you care about — a loved one or friend — and

you’ve had a gross miscommunication, you may want to explain yourself in

an effort to preserve the relationship.

But, if the critical/offended/skeptical party is someone you

don’t know personally (like a stranger online or the public in general),

don’t care about, and/or

don’t

respect as an equal — someone who shouldn’t have any say or sway over

your choices — then taking the time to explain why they’re wrong, or why

you’ve made the decisions you have, is ill-advised.

To be concerned with what someone outside your circle of respect

thinks, is to allow yourself to be pulled down to his or her level.

Explaining yourself is essentially an

attempt to seek another’s approval. It shows you’re stung that they’ve

withdrawn that approval, and desirous of getting it back. When you show

that you care about an opinion that you, and any observers, know you

really shouldn’t, you show weakness. In losing the fight between trying

to ignore them and craving the catharsis of engagement, you demonstrate a

failure of self-control.

Further, when a chucklehead elicits a response, you validate his

importance. He’s made you do something against your better judgment.

You’ve given to him two of your most precious resources – your time and

attention. You’ve gone from the offensive to the

defensive. His

status goes up and yours goes down.

People — whether irrationally angry customers, estranged family

members, or a controlling significant other — will often demand

explanations for what you do. They’ll say you are weak if you don’t

offer one. But this is the cleverest of ploys! By targeting your pride,

they’ll get you to hand over your power.

Of course restraining yourself from responding to someone who’s

goading you on is easier said than done! As someone who’s subjected to a

constant barrage of feedback on my work, day after day, I find I am

able to successfully ignore about 98% of it. It’s when someone says

something that impinges on my honor (even when I know they’re not part

of my honor group), or when they

seem like a dude I can have a good debate with that I get in trouble.

When someone is clearly off their rocker, it’s easy to ignore them as

really out there. And when someone has something critical but

intelligent to say, engaging them can actually be interesting and

instructive. It’s the people who greatly distort who you are/what you

did/what you said, but mix together sensible sounding discourse with

nuggets of crazy, who prove the most irresistible. They

almost sound like someone you can have a reasonable discussion with; it

almost

seems like you could explain to them why they’re objectively off the

mark. But as it invariably turns out (and this is a lesson I have to

learn over and over!), if someone’s mindset/mentality is such that

they’re able to grossly misinterpret something, no amount of explanation

— no matter how thorough and well-reasoned — is going to change their

mind. Quite to the contrary — they’ll simply dig in their heels all the

more!

“Never complain; never explain” doesn’t

necessarily mean not saying anything to your doubters, complainers, and

critics, but limiting your response to a sharp rejoinder. Disraeli in

fact formulated his maxim after hearing the advice of fellow politician

Lord Lyndhurst, who said: “Never defend yourself before a popular

assembly except with and by retorting an attack.” Thus, a short, pithy

rebuttal or a humorous, yet withering sarcastic quip (Churchill was the

master of these) may be in order. Then you turn heel and don’t engage

further.

Of course, even a simple retort may draw you into an argument you

never wanted to have, which often makes complete silence the best

possible response. In fact, nothing drives someone nipping at you heels

crazier than to have their questions and demands go utterly ignored and

unacknowledged.

Explaining demonstrates a lack of confidence in your choices/creations/principles.

Have you ever been looking at a book or product on Amazon and seen that

its author or manufacturer has jumped in and responded to people’s

negative reviews? I don’t know about anyone else, but for me, even if

the negative reviewer sounds like a real ding-dong, and the rebuttal is

reasonable, well-done, and conciliatory, I still end up thinking less of

the author/company, and cringing a bit on their behalf.

Most everyone knows that authors and companies check in on their

reviews at least occasionally, but when you give people demonstrable

proof that

you’re hovering around, you confirm your insecurity and/or vanity and

thus show weakness and a lack of confidence in your work. In stepping

from the ranks of the creator, to that of the consumer, you lose status.

If you arrived at your creative vision or

set of principles for good reasons, if you said everything you wanted to

say, in the best, clearest way you knew how to say it, and endeavor

only to put out your very best work, then you can be content to let your

decisions and your work stand on its own. You have nothing else to add.

People either get what you do and are about, or they don’t.

There will always be those who twist your words, or misinterpret your

meaning, or don’t find your design sense to their liking and mistake

their subjective taste for objective truth. If you’d rather make money

than stay true to your creative vision, then by all means, try to

explain and change the minds of those unhappy with your work. Try to

hold onto all the customers you can. I don’t mean this sarcastically;

sometimes products are not vessels of your values, but merely

utilitarian, and it can make sense to be very connected to the needs of

your customers.

But, if you’d rather fail and have to try something else, than change

your ideas and principles to suit the tastes of others, then choose to

be like Jack London, who felt that the public continually misunderstood

his work, and contented himself by deciding: “The world is mostly

bone-head and nearly all boob.”

Or as the British academic Benjamin Jowett put it: “Never retract. Never explain. Get it done and let them howl!”

Explanations easily turn into excuses. Naturally,

even when you endeavor to give people your best, unforeseen problems do

sometimes arise. When you’ve objectively messed up, should you explain

to people what happened?

People do typically appreciate a little

explanation as to the what, when, and why of your blunder. But the

explanatory part of your apology should be kept short — for as Lord

Acton, yet another explanation-spurning British politician warns: “Beware of too much explaining, lest we end by too much excusing.”

You should pivot as quickly as possible to taking responsibility and

saying how you’re going to make things right. In the words of an old

proverb: “Don’t make excuses; make good.”

While “never explain” and “never complain” are two discrete parts of

the couplet, a common thread runs through them: autonomy and

accountability.

Once you understand why you should rarely

explain, you should understand why you should rarely complain. You

simply put yourself in the shoes of the party you’re seeking an

explanation from, and act accordingly.

If a person or company has failed to meet their own clearly

delineated standards, you can of course ask for an apology or file a

complaint, asking for your money back or what have you. Keep the

explanation for your unhappiness short, moving as quickly as possible

into what you’d like them to do to make it right.

If you think your feedback could help someone improve something,

offer it in a constructive way.

If you’re in a situation where a complaint will accomplish nothing, then common sense dictates that you should remain silent.

If you’re in a situation where complaining will accomplish far less

than going about trying to make the desired changes yourself,

choose action over whining.

And if you’re tempted to complain about something on the basis of

subjective taste, reconsider.

For the party you seek to complain against has a purpose and vision outside of your own needs and desires.

Take professor evaluations in college, for example. Some students

will complain that the professor “sucks” because his coursework is

challenging, while others students will praise him

because the

coursework is so challenging. The professor has a purpose and a set of

principles all his own, and while you might disagree with him, and

decide never to take another of his classes, why complain that his

priorities are not more like yours? If people complained against your

vision or work, you shouldn’t care, so why should he?

I once read an interview with Ben and Jerry —

the ice cream makers — in which they said they wished they could

forward one set of the letters they received to the senders of another

set. Because some people would write saying they wished their ice cream

had less/smaller chunks of things, while others would write saying they

wished the chunks were even bigger and more numerous. Which complainers

did Ben and Jerry listen to? Neither, of course. They stuck with their

own vision of what constituted the best kind of ice cream, and the

heavens rained down dough of both the monetary and cookie varieties.

I’ve gone out to dinner a couple of times where the experience was so

bad, I felt I couldn’t wait to get home to write a bad review of the

place online. But invariably, that feeling would dissipate, and I’ve

never written a bad review of anything in my life. Because

ultimately…who cares? Maybe my experience was atypical, or maybe some

people like the food that I thought was completely gross. The

restaurateur is doing things the way he wants to do them, and I’m

content to let the market decide whether his vision is a good one or

not.

The world doesn’t exist to meet my expectations, and if they’re not

met, I figure I can do one of two things — go somewhere else, or create

something myself more to my liking.

I never complain because I don’t think I should have to explain

myself to other people, and I don’t think other people should have to

explain themselves to me!

World War II U.S. Army officers wearing the “pinks and greens” uniform

World War II U.S. Army officers wearing the “pinks and greens” uniform