Soviet Navy Trawler "Fishing"

We played games with them, it was understood that there were rules to this game and the NORKS broke the rules when they seized the ship. I don't blame the Captain having to surrender, trying to save the lives of his crew after getting attacked by overwhelming NORK forces. They seize the ship and try the crew for "spying". What I can't understand is why didn't we bomb the ship, I remember when an American warship was captured by the Barbary pirates, a young lieutenant named Stephen Decatur and a sloop called the "Intrepid" sailed into the harbor and boarded the U.S.S. Philadelphia and tried to sail her away but were unable to so they destroyed the ship. I know that during the Cold war, we had submarines in the Berent sea and by the Kola Peninsula sneak into the Soviet harbors and tap the communications cables. and a bunch of other really sneaky stuff that still is classified to this day. What get me is why didn't we sneak into the harbor, either like the French DGSE did with the Rainbow Warrior and sink the ship rather than keep allowing it to be used as a propaganda trophy by the NORKS. I got this information of the Tripoli raid from "Wiki" Like I said, this is my opinion and not supported by any body else private or government.On October 31, 1803, Philadelphia, under the command of Commodore William Bainbridge, ran aground on an uncharted reef (known as Kaliusa reef) near Tripoli's harbor. After desperate and failed attempts to refloat the ship she was subsequently captured and her crew imprisoned by Tripolitan forces. In an elaborate plan put together by Lieutenant Decatur, Decatur sailed for Tripoli with 80 volunteers (most of them being U.S. Marines) intending to enter the harbor with Intrepid without suspicion to board and set ablaze the frigate Philadelphia, denying its use to the corsairs. USS Syren, commanded by Lieutenant Charles Stewart, accompanied Intrepid to provide supporting fire during and after the assault. Before entering the harbor eight sailors from Syren boarded Intrepid, including Thomas Macdonough who had recently served aboard Philadelphia and knew the ship's layout intimately.

On February 16, 1804, at seven o'clock in the evening under the dim light of a waxing crescent moon, Intrepid slowly sailed into Tripoli harbor. Decatur's vessel was made to look like a common merchant ship from Malta and was outfitted with British colours. To further avoid suspicion, on board were five Sicilian volunteers including the pilot Salvador Catalano, who spoke Arabic. The boarding party remained hidden below in position, prepared to board the captured Philadelphia. The men were divided into several groups, each assigned to secure given areas of the ship, with the additional explicit instruction of refraining from the use of firearms unless it proved absolutely necessary.As Decatur's ship came closer to Philadelphia, Catalano called out to the harbor personnel in Arabic that their ship had lost its anchors during a recent storm and was seeking refuge at Tripoli for repairs. By 9:30 p.m. Decatur's ship was within 200 yards of Philadelphia, whose lower yards were now resting on the deck with her foremast missing, as Bainbridge had ordered it cut away and had also jettisoned some of her guns in a futile effort to refloat the ship by lightening her load.

As Decatur approached the berthed Philadelphia he encountered a light wind that made his approach tedious. He had to casually position his ship close enough to Philadelphia to allow his men to board while not creating any suspicion. When the two vessels were finally close enough, Catalano obtained permission for Decatur to tie Intrepid to the captured Philadelphia. Decatur surprised the few Tripolitans on board when he shouted the order "board!", signaling to the hidden crew below to emerge and storm the captured ship. Without losing a single man, Decatur and 60 of his men, dressed as Maltese sailors or Arab seamen and armed with swords and boarding pikes, boarded and reclaimed Philadelphia in less than 10 minutes, killing at least 20 of the Tripolitan crew, capturing one wounded crewman, and forcing the rest to flee by jumping overboard. Only one of Decatur's men was slightly wounded by a saber blade. There was hope that the small boarding crew could launch the captured ship, but the vessel was in no condition to set sail for the open sea. Decatur soon realized that the small Intrepid could not tow the larger and heavier warship out of the harbor. Commodore Preble's order to Decatur was to destroy the ship where she berthed as a last resort, if Philadelphia was unseaworthy. With the ship secure, Decatur's crew began placing combustibles about Philadelphia with orders to set her ablaze. After making sure the fire was large enough to sustain itself, Decatur ordered his men to abandon the ship and was the last man to leave Philadelphia. As the flames intensified, the guns aboard Philadelphia, all loaded and ready for battle, became heated and began discharging, some firing into the town and shore batteries, while the ropes securing the ship burned off, allowing the vessel to drift into the rocks at the western entrance of the harbor.

While Intrepid was under fire from the Tripolitans who were now gathering along the shore and in small boats, the larger Syren was nearby providing covering fire at the Tripolitan shore batteries and gunboats. Decatur and his men left the burning vessel in Tripoli's harbor and set sail for the open sea, barely escaping in the confusion. With the cover of night helping to obscure the enemy gunfire, Intrepid and Syren made their way back to Syracuse, arriving February 18. After learning of Decatur's daring capture and destruction of Philadelphia without suffering a single fatality, British Vice Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson, who at the time was blockading the French port at Toulon, claimed that it was "the most bold and daring act of the Age." Decatur's daring and successful burning of Philadelphia made him an immediate national hero in the US.Appreciation for the efforts of Preble and Decatur were not limited to their peers and countrymen. At Naples, Decatur was praised and dubbed "Terror of the Foe" by the local media. Upon hearing the news of their victory in Tripoli, Pope Pius VII publicly declared that "the United States, though in their infancy, had done more to humble and humiliate the anti-Christian barbarians on the African coast in one night than all the European states had done for a long period of time." Upon his return to Syracuse, Decatur resumed command of Enterprise.

In Pyongyang, the North Korean Government keeps a trophy from 1968. Moored on the Botong River, alongside the Pyongyang Victorious War Museum sits the USS Pueblo (AGER-2).

It’s the second oldest still-commissioned U.S. Navy ship, and the only one held captive by another country.

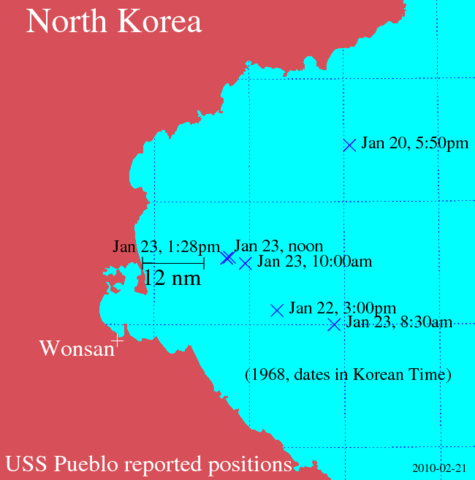

The incident when North Korea seized the Pueblo along with her 83 crew members, killing one of them and wounding many others, occurred on January 23rd, 1968, a week before the start of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam. U.S. officials believed at the time that the North Koreans were acting upon instructions from the USSR (though this was confirmed to be untrue years later) and Cold War tensions were raised to one of the highest levels since the Cuban Missile Crisis a little more than five years earlier.

The crew was held for 11 months of negotiations between the U.S. and North Korea and were starved and tortured while in captivity. Many people reading this are probably not old enough to remember events like the Cuban Missile Crisis or even the Iran Hostage Crisis (1979-81).

For those who are too young, to give a sense of the intensity and fear in this situation, keep in mind that President Lyndon B. Johnson had officials advising him to demand the immediate return of the hostages from North Korea under threat of Nuclear Attack.

The Pueblo wasn’t exactly taking a leisurely cruise around waters East of North Korea. It was a U.S. Auxiliary General Environmental Research (AGER) vessel under a program conducted by the Naval Security Group and the National Security Agency. Lead by Commander Lloyd M. Bucher, the Pueblo’s crew was there to gather intelligence and signal data from North Korea.

Vital to understanding the tensions surrounding this incident is the failed assassination attempt on South Korean President Park Chung-hee on the 22nd, of which the crew of Pueblo was not informed. Thirty-one North Koreans slipped over the border and tried to infiltrate the “Blue House” where the president resided, but were thwarted.

The next day, the 23rd, Pueblo was approached by another North Korean submarine chaser whose officers challenged Pueblo’s nationality. When the Pueblo’s U.S. flag was raised, she was ordered to stand down or be fired upon.

Though the Pueblo had some light weaponry, Bucher knew a firefight wasn’t an option, that time was their greatest hope. According to the Operations Officer of the Pueblo, Skip Schumacher, this was the matchup: “The PUEBLO had no armor protection whatsoever; its armaments consisted of 10 Browning semi-automatic rifles, a handful of .45 caliber pistols and two .50 caliber machine guns wrapped in frozen tarps on the starboard and aft rails. With these tools it was asked to fend off 4 torpedo boats, 2 submarine chasers and MiG jet aircraft. Not very good odds”

As the Pueblo tried to flee, she was fired upon, without so much as a warning shot. One crewman was killed and 18 injured in the attack. Bucher broke off the run and surrendered to save the rest of his crew.

Schumacher also describes a startling realization of the ship’s vulnerability and the huge game-changer that this incident was as the North Koreans broke the de-facto rules of the cat-and-mouse, push-and-pull spy game that existed at the time and opened a chapter of full-out aggressive action.

The North Korean regime, then as now, leaned heavily on their propaganda machine to instill their rule in the minds of their people and other nations. As they were forced to pose in photographs for this propaganda, the Americans, shot after shot, posed flipping their middle fingers, telling their captors at the time that it was a Hawaiian good luck gesture. When the North Koreans found out the true meaning of their mockery, the torture and starvation of the crew were increased.

Through the almost year-long imprisonment of the crew, slow, agitating negotiations were held between North Korean and U.S. officials at Panmunjom, the village where the armistice ending the full-out conflict of the Korean War was signed in 1953. Cultural and ideological differences made, what we would call in the West, decent compromise impossible.

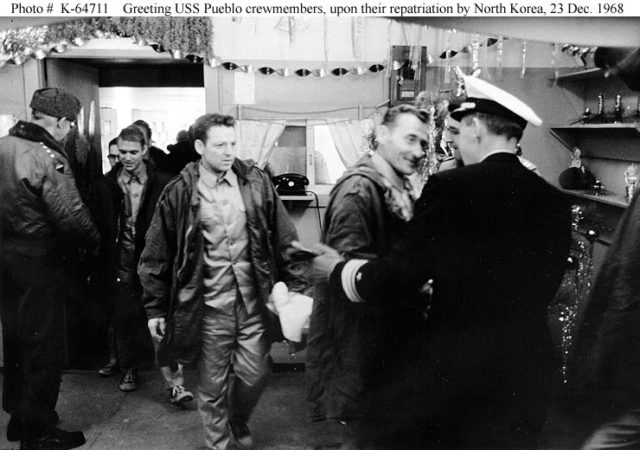

In the end, U.S. Army Major General Gilbert H. Woodward signed a full apology for the Pueblo spying on their nation and a promise that it wouldn’t happen again, and the North Koreans bussed the 82 remaining crew to the DMZ and handed them over. The apology and promise were hastily retracted.

In the following years, the commander and crew of the Pueblo were spared a court-marshal, with Secretary of the Navy John Chafee stating that the crew had been through enough. The North Koreans and Soviets were able to reverse-engineer the Pueblo’s communication devices, which gave them great insight into the communication of the U.S. Navy until the late 1980s.

The crew also had to wait until 1990 before their almost year-long ordeal was official recognized by the U.S. government and awards were given.

Blame for that falls on LBJ... sigh...

ReplyDelete